Last June around this time we had just launched our blog. We then traveled to Cuba together, as we had dreamed of doing for years, seeking to strengthen our bridge of friendship as we embarked on this project of literary/artistic bridges to and from Cuba. We are so honored by all the warm support we’ve received throughout the past year for our blog. Thank you to all our readers and writers! As we move forward, with hope and optimism, to another year of bridge-building, we are delighted to feature a deeply searching essay by renowned political scientist María de los Ángeles Torres, known to her many friends simply as Nenita. Looking back at the emotional debate that ensued as Fathom prepared to launch the first cruise to Cuba from Miami, Nenita draws out the important moral and practical lessons to keep in mind as bridges cease to be romantic dreams and become anchored in the complex realities of political negotiation. We hope you’ll find the piece as compelling as we do. Let us know what you think and add your voice to the debate!

Abrazos,

Ruth & Richard

by María de los Ángeles Torres

Barquito de papel,

mi amigo fiel,

llévame a navegar,

por el ancho mar.

Quiero conocer,

a niños de aquí y de allá,

y a todos llevar

mi flor de amistad.

¡Abajo la guerra!

¡Arriba la paz!

Los niños queremos

reir y cantar.

⏤Enriqueta Almanza

Little paper boat,

my loyal friend,

take me sailing

across the wide sea.

I want to meet

kids from here and there

and bring them all

the flower of my friendship.

Down with war!

Hooray for peace!

We kids just want

to laugh and sing.

⏤Enriqueta Almanza (translated by David Frye)

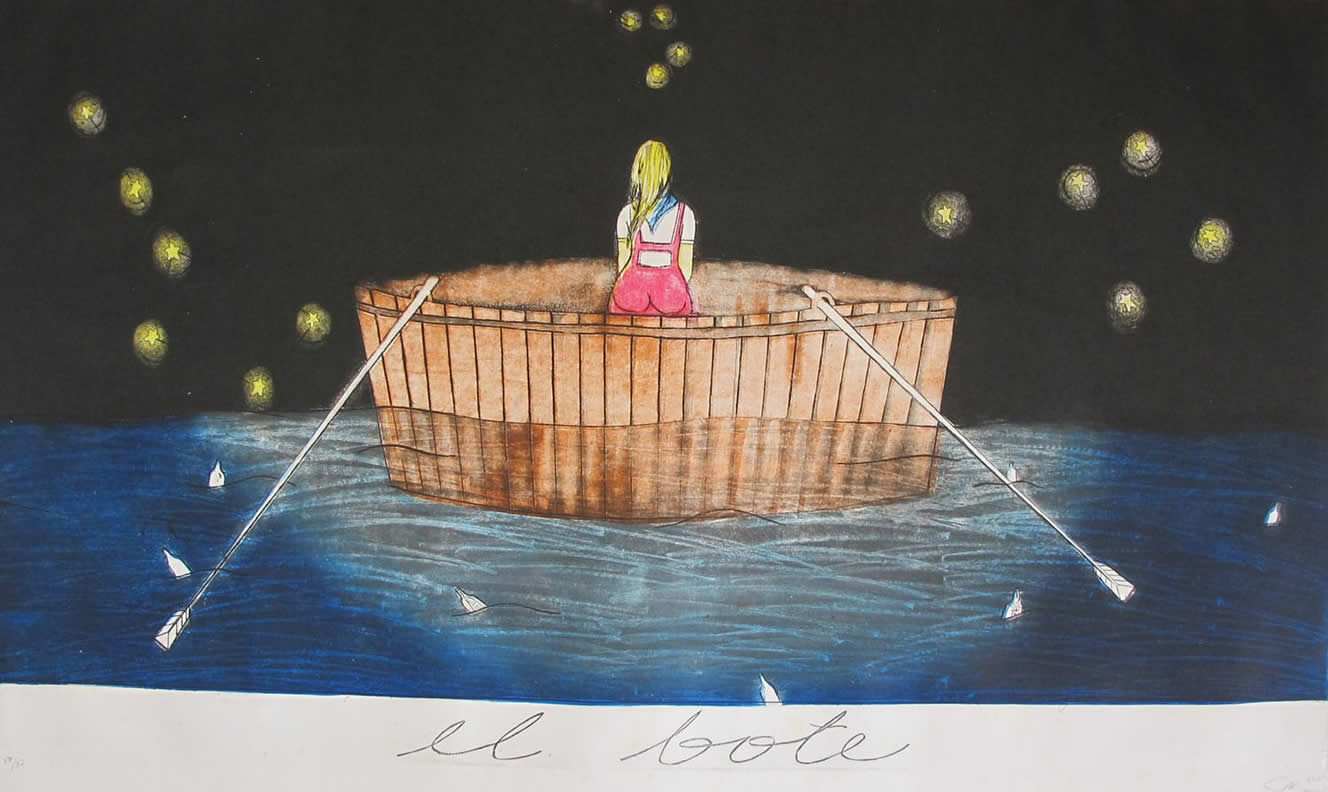

Art courtesy of Sandra Ramos

Since 1975, I have been involved, in one way or another, in trying to better relations between my two countries. These have not been easy waters to navigate. Obama’s trip to Cuba this past March felt like the culmination of my forty-year journey to build better relations between the country of my birth and the one I now live in. In his moving speech delivered at el Gran Teatro de La Habana, he addressed U.S. and Cuba relations, and also recognized the complicated relationship we Cuban-Americans have with the island and why our contributions have been vital to the United States and to Cuba’s future. I thought our barquitos de papel, filled with hopes of rapprochement, had finally arrived.

The first sign of a new era was to allow Fathom, the educational division of Carnival Cruises, a Miami-based company, to sail to Cuba. Unfortunately, it did not reflect Obama’s more nuanced transnational perspective, or for that matter his commitment to civil rights.

I first heard about the cruises from Orbert Davis, the gentle trumpet player, composer, and director of the Chicago Jazz Philharmonic Orchestra. He had been invited to play on board one of the first Fathom cruises that was to sail to Cuba in May. Orbert had asked to bring on board some of the student players from Cuba who had been in Chicago in the fall, to join his orchestra and sail from Havana to Cienfuegos and Santiago. However, Orbert was denied permission because of some arcane Cuban regulation that did not permit Cubans to travel by boat or ship in national waters. We bristled at the absurdities that literally had to be navigated in order to establish cultural exchanges with Cuba.

I have to admit I had never wanted to go on a cruise before, but this one would feature music that I loved. Jazz has been a bridge not only to the United States but also to my island past. Both of my parents loved jazz; my mother attended Nat King Cole concerts in Havana, and “My Foolish Heart” was the first song she and my father danced to. I thought the cruise could be a way to bring together my Chicago and Havana lives through music and especially jazz. However, when I tried to book my trip, I was informed that the archaic regulation also applied to Cuban-Americans as well. I received an email that said:

“Thank you for contacting Fathom! Currently Cuban policy prevents Cuban-born individuals from traveling to Cuba by boat or ship. Because of this Cuban policy, we are not accepting bookings from Cuban-born individuals at this time.”

I started making calls, first to friends in the White House, who had no idea that the provision was included in an agreement that they had approved and helped negotiate, claiming that it would be appalling if it was. I called other Cuban-Americans, Carnival representatives, and even their lawyers, who reiterated that they could not sell me a ticket because I was born in Cuba. The island of Cuba had a regulation that prohibited Cuban-born travelers, regardless of citizenship, to navigate Cuban waters without a permit to navigate.

I have spent years studying Cuba’s immigration policies, but this one stumped me. My first aim was to understand what this permiso de navegación was all about. I searched the internet and learned that this centuries-old practice originated in Spanish colonial times as a way to control navigation to the Americas. One site led me to Ebay, where an 1827 antique permiso de navegación can be bought for 490 euros. I don’t know how much it cost at the time, but I imagine this was a way for the Spanish government to make money. I can also speculate that others were worried about unauthorized ships navigating in Cuban waters; after all, pirates were menaces to the colonial enterprise. Money and security concerns have a way of codifying policies that stubbornly live beyond their original purpose .

As far as I could find, the permiso de navegación was first introduced in Cuba by the Spaniards and later codified into law by an order of the U.S. Paradoxically, in the early 1960s the revolutionary government used this U.S. order as a way to punish unauthorized vessels entering Cuban waters, fearing they could be bringing anti-Castro invaders. More recently, those who are leaving the island are the target of this regulation. It got traction as a repressive mechanism in the 1990s, as thousands of people were leaving on anything that floated. One group tried to leave on the 13 de marzo tugboat, only to be chased by the Cuban Coast Guard, who stopped it by sinking it with powerful naval guns. Forty-one Cubans drowned.

Most recently there has been an uptick in people leaving the island—some are even calling it a silent Mariel. The permiso de navegación has become an even more powerful emigration control mechanism, and those caught in Cuban waters without it face three years of prison time. Inadvertently, it has also prohibited Cubans from being on recreational water vehicles, waterskis, windsurfs and cruise ships. For the purposes of this regulation, we were counted as Cuban nationals.

In Carnival’s enthusiasm to be the first cruise line to sail to Cuba in more than fifty years, it acquiesced to this Cuban regulation, effectively bringing to U.S. shores a provision that would have prohibited a class of individuals from boarding its cruise ships based on national origin.

Many of us came to the United States in the midst of the Civil Rights movement. Although the Cuban exile enclave shielded many from the effects of discrimination, those of us raised outside of Miami had countless raw experiences with it. In Texas, where I was raised, I remember being denied entrance into swimming pools, restaurants, and public bathrooms because I was Cuban. It was the root of my political activism. Carnival’s initial support of a policy that discriminated against U.S. citizens and legal residents born in Cuba was, in effect, no different since its implementation excluded a class of people based on their national origin.

I was not the only one incensed. A network of Cuban-American friends came together. Fabiola Santiago wrote a moving column in the Miami Herald asking a simple question: would Carnival have prohibited African-Americans from traveling on cruises to South Africa if they had been offered during the apartheid? I asked the jazz musicians in Chicago who were going on the cruise how they would have felt about the folks who went on cruises that excluded African-Americans. An online petition was launched and calls were made to the White House. Cuban-Americans from all sides of the U.S./Cuba political spectrum condemned Carnival cruises for discriminating against a group based on its national origin.

Eventually two lawsuits were filed. These landed in U.S. District Judge Marcia Cooke’s courtroom, who said it was clear to her that the policy of not selling tickets to Cuban-Americans was discriminatory under U.S. law. The courts had established that cruise ships are public accommodations and as such are subject to civil rights laws. By the time of the hearing, Carnival had changed its policies and had started selling tickets to Cuban-born passengers, stating that it would not sail until Cuba changed its regulation. Cuban officials eventually changed the provision of the arcane regulation.

Still, Judge Cooke, an African-American with a keen sense of how discrimination is structured, warned that even with these changes Cuban-born citizens appeared to have more hurdles to clear to get travel visas, something she compared to past racial discrimination. She was quoted in a Naples News article, saying, “I am equating this to the old voting test requirements in the American South.”

The policy of rapprochement increases our opportunities to discuss more than simply whether or not to engage Cuba. As such, the debate now concerns the principles and legal and ethical frameworks with which to manage U.S.-Cuban relations. In this case, engagement allowed us to challenge a repressive Cuban regulation that violated basic civil rights laws when applied in the context of United States laws. When the Cuban government changed the provision, it did so for all Cubans, including those living on the island.

Engagement allows us to shine a light on the disparate cottage industries that have popped up under the shadows of the embargo, both in Cuba and the United States. We can question practices that emerge on the island that in the context of the United States result in discriminatory practices. At the same time, we also can and must ask how it is that every U.S. charter company that does business with Cuba comes up with the same price. Are anti-trust laws being violated? What about fair pricing for consumers? And because we are citizens of the United States, we can also challenge American corporations, even ones as popular and powerful as Carnival, when their practices result in violations of U.S. law.

The absence of meaningful engagement between Cuba and the U.S. for almost sixty years means that there will, inevitably, be other moments of disjuncture. But I and many other Cuban-Americans have not spent forty years building bridges only to be excluded from crossing them, or for that matter, for these bridges to serve as a crossing point for the Cuban government’s repressive practices to come to the shores of the United States. To that end, we now have this small victory ensuring that all Cubans will not be excluded from navigating in Cuban waters. That is why, as I reflect on this new chapter in Cuba-U.S. negotiations, I can’t help but think of the children’s song about the paper boat, the barquito de papel, written by Enriqueta Almanza. We still hope for better relations, knowing that navigating these waters will be more complicated yet may yield positive changes on both sides of the aquatic divide.

María de los Ángeles Torres is executive director of the Inter-University Program for Latino Research and is professor of Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She has written extensively on Latinos, politics and identity, and immigration, and has authored In the Land of Mirrors: The Politics of Cuban Exiles in the United States and The Lost Apple: Operation Pedro Pan, Cuban Children in the US and the Promise of a Better Future; co-authored Citizens in the Present: Civically Engaged Youth in the Americas, edited By Heart/De Memoria: Cuban Women’s Journeys in and Out of Exile and co-edited Borderless Borders Latinos, Latin American and the Paradoxes of Interdependence and Global Cities and Immigrants, The Case of Chicago and Madrid. She is currently working on a manuscript, The Elusive Present: Temporalities in Cuban Thought. She is part of a team working on compiling a virtual collection of One Hundred Years of Chicago Latino Art.

Eduardo Aparicio, born in Guanabacoa, Cuba, lives in Austin, Texas. He is a writer, translator, and photographer.

Sandra Ramos lives and works between Miami & Havana. She is one of Cuban’s best-known contemporary artists from the 90s Generation. Through a compelling visual dialogue, Ramos has gained an international reputation by expressing her personal relationship to Cuba’s political and social realities. In her work she uses a wide range of materials and techniques as engraving, painting, video and installation. References to familiar characters from Cuban literature, history and folklore are found in her art; she uses these wisely to make critical statements related to the context of her life & artwork. Ramos studied at the prestigious San Alejandro Art Academy and The Superior Institute of Art, (ISA) both in Havana. She has exhibited extensively for over twenty years at venues which include: ASU Art Museum, Venice Biennial; Havana Biennial; Museo de Bellas Artes, Havana; The Jewish Museum,NY; American University Museum, Washington; MOMA, NY; Bronx Museum, NY; Museo Del Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City; Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, Vienna; Sheldon Museum of Art, Nebraska; Lyman Allyn Art Museum, New London; Ringling Museum, Tampa, FL; Fuchu Museum, Tokyo. Her work is included in the collections of the MOMA, NY; The MFA, Boston; The San Diego Museum of Art, CA; PAMM, Perez Art Museum. Miami and The Ludwig Forum für Internationale Kunst, Aachen, among others worldwide.

Wonderful article by Nenita!