We’re delighted to share this evocative piece by Caridad Moro-Gronlier, who writes lovingly about the complexities of her relationship with her mother in the context of family dynamics. Caught in an emotional triangle between her mother and her cousin Pepe, who remained in Cuba, Caridad muses over the power of language in building, re-establishing, or mending relationships through words that free us with honesty and let us discover empathy for ourselves and for others. By contrast, Caridad also speaks about the price of silence that can imprison us within ourselves. We hope you’ll enjoy the piece in its original English form as well as in the beautiful translation to Spanish by Eduardo Aparicio.

By Caridad Moro-Gronlier

All my life, friends and strangers have remarked on how much I look like my mother, but those who really know me know that my likeness to her does not extend to demeanor. Much to her chagrin, my mother has never understood my need to reveal my thoughts and emotions on such a consistent (relentless, she’d say) basis. She is the epitome of restraint and reserve. Never was this made clearer to me than in March of last year, during one of our monthly gossip-and-vent lunches at a jazz-filled bistro in the Miami Design District. We had been there for hours, flushed with wine and risotto, lulled by the rhythm of easy banter, our conversation laced with tidbits of information we had saved to share with one another, but it wasn’t until I began to stir raw sugar into my espresso that she dropped the biggest bomb of the day.

“Por poco se me olvida,” she said, “I almost forgot; when your tía went to Cuba last month she saw Pepito and he gave her an email where we can write to him. Do you want it?”

Pepe, the thinker, the scholar, the English professor who has always contended he dreams in sonnets.

Pepe, the beloved first cousin whom she was forced to leave behind. A year her senior, at sixteen he had been deemed eligible for military service and as such, ineligible for an exit visa. Bad timing rooted him to the spot, rendered him the trunk of our family tree, trimmed free of all but a few of its flowering branches.

The last picture Cary’s mother Mercedes took with Pepe, in June of 1964 before she and her family left Cuba. Mercedes is the girl to the left and Pepe is the tallest boy standing next to her.

We have never met. All images I’ve ever seen of him are devoid of color so I do not know the exact shade of his hair or eyes. I have never heard the timbre of his laugh or the cadence of his footsteps. I don’t know if his nose reddens when he cries or if he whistles to stave off rage. I have never greeted him with a kiss on the cheek, or squeezed his hand good-bye.

Yet, whatever yearning my heart holds for Cuba is wrapped up in him.

“Of course, I want it.” I said, exasperated, “but why did you wait so long to tell me?”

“Escríbele pronto,” my mother answered, ignoring my rebuke. “Write to him soon. He’d love to hear from you.”

Our unlikely friendship began shortly after my tenth birthday. For three years we exchanged letters. Beautiful letters that arrived in airmail envelopes bordered in red and blue chevrons, their faces tattooed with an array of postage, their long journey confirmed by the emblazoned blue silhouette of a plane—to date, the only wings that have ever flown me to Havana.

Pepe’s letters were filled with questions about my hopes, my dreams, my wants, my fears, all in an attempt to get to know me—“What subject do you like most in school?” “What would you like to study in the future?” “What books are you reading?” “Who are your best friends?” “And your brother, what about him, is he good to you?” Questions I never quite answered.

Cary, age 10, writing to Pepe.

To my knowledge, my mother has never read Emily Dickinson, but back then, when it came to crafting a response, she taught me to “tell all the truth but tell it slant.” Her censorship was benevolent, but absolute. She checked my letters for misplaced acentos, awkwardly conjugated verbs and content that might upset the great Cuban juggernaut: El que dirán.

Simply put, El que dirán was the unspoken understanding that our actions were destined to be judged, scrutinized and criticized by everyone we knew, and possibly, even those we didn’t know. A raised eyebrow was enough to regulate my words, my behavior, and I lived with the omnipresent fear of letting her down, of exposing my entire family to the flames of disapproval and gossip. Line by line, my letters were whittled down until they were little more than talky newsletters. My sheets of Hello Kitty stationery were sanitized, scrubbed free of mistakes, fear, anger, regret, scrubbed free of me. The message was clear—truth could easily turn treacherous, and I began to edit myself so as to protect my letters from my mother’s laser sharp inspection.

I wanted to tell Pepe that, yes, I loved my brother very much, but that every time he pushed back from the dining table and plopped in front of the TV, leaving me to clear and scrape and wash the dinner dishes, I loved him a little less—but I didn’t. I wanted to tell Pepe that I could feel the blood rush to my hands and face every time I watched my father dole out my mother’s allowance once a week, a mere ten dollars that she usually spent on us rather than herself—but I didn’t. I wanted to tell Pepe that when I made my father angry he’d ignore me for weeks, that his silence stung more than a spanking—but I didn’t.

At around age thirteen, I decided that my mother’s approach to diplomacy was untenable. I could no longer participate in my own erasure, as the bulk of all the sentences I didn’t write filled the pit of my stomach until I could no longer choke back the words I was not allowed to share with Pepe. I would simply stop writing, I decided. To quote Robert Hayden, “What did I know?”

It was easy to blame my mother, to lay my disdain at the feet of her fear—fear of being judged, fear of causing Pepe some unintended harm. It was easy to scoff at one of the central tenets of her life—that the wolf was always at the door. As a result, we had to be careful, shield our thoughts, our emotions, our beliefs, because those things made us vulnerable and had the power to get us into trouble.

It took more years than I care to admit to realize that my mother’s fear provided the bedrock of my courage. Yes, she looked over my shoulder, scratched out sentences that might have been misconstrued or potentially found offensive, but she also sharpened my pencils and kept me in stamps and provided me with the safety net of her love, no matter how much we fought over what to leave in, what to leave out. My mother was my first editor, my fiercest critic, and to this day, my most loyal supporter, always beautifully dressed and reliably poised, her face lit by the megawatt smile she beams toward me from the front row at every single one of my poetry readings.

Cary and her mother, 2015.

Thirty-five years later, I can say that I became a woman who lives as she pleases, who says what she thinks, who is unencumbered by the shackles of El Que Dirán. Yet, as I face the blinking cursor on the blank screen that is the email I have begun to write to Pepe, I realize that fear is a tricky thing. That it has seeped into my skin in unexpected ways that cast a pall on what I have always believed about myself. For all my bravado, I don’t know how to begin. Not because I don’t have scores of things to say, but because suddenly, I am stymied by one question: ¿Qué dirá Pepe de mí? What will Pepe think of me?

“There will be time, there will be time. / To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet.” So says T.S. Eliot, and that’s exactly what I do, “I prepare a face” for Pepe—the face of the English professor I grew up to be, molded in part by his example; the face of the poet whose love of poetry began as a girl, inspired by the copy of La Edad de Oro he sent me so many years ago; the face of the mother I also became, who is proud of a son so intelligent and good-hearted that I am forever shocked by the knowledge that his bones were knit within the expanse of my body; the face of a daughter, who remembers the words of her mother, who still longs to make her proud, who worries about the weight of the truth I am loathe to reveal.

I say nothing to Pepe of my painful divorce a decade earlier, that leaving my husband, a good man whom I still love and who still loves me back, was one of the scariest, most difficult things I have ever done. I do not tell Pepe that I rose above the terror of being called dyke, lesbo, tortillera because I was embraced by a family (yes, even my father) who loved me simply for being me. I do not tell him that I am happily re-married. I do not tell him my wife’s name.

His response is swift and effusive, filled with questions, just as before. He tells me that there is much he could write of his loss and sorrow, but instead he quotes Kipling,

“…lose, and start again at your beginnings / And never breathe a word about your loss,” a line that hits me like a fist.

How is it that I can’t remember a single letter in which he complained? Throughout our entire correspondence, never once did he speak of his lack, his want, his sorrow, his rage. Perhaps worse is the fact that never once did I think to ask. I could chalk my shortsightedness up to childish egocentricity, which in part it was, but it also speaks to the transcendent nature of censorship, how it colored not only what I was afraid to say, but what I was afraid to ask, afraid to know.

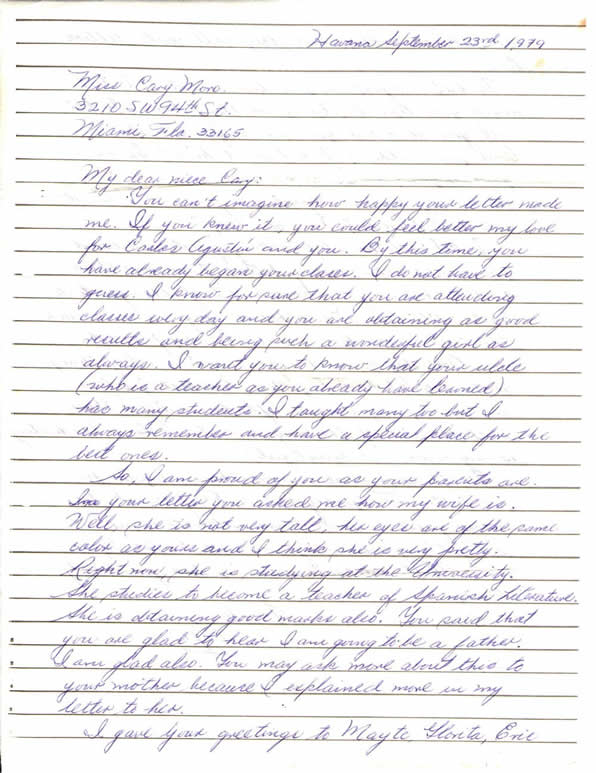

A letter from Pepe.

I no longer feel afraid as I grasp the line of verse Pepe throws out to me. I tether it to the dock of my heart and realize that his words provide just the viaduct I need to send him my un-slanted truth.

“Ignore Kipling,” I write, “as beautiful as his advice may be, I think that it is time that we both exhale. The time has come to breathe, to release our loss. Let us both heed Mary Oliver instead—‘Tell me about your despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.’”

“I will go first,” I write, “My wife’s name is Elizabeth.”

Caridad Moro-Gronlier is author of Visionware, published by Finishing Line Press as part of their New Women’s Voices Series. She is the recipient of an Elizabeth George Foundation Grant for Poetry and a Florida Individual Artist Fellowship in poetry. Recent projects include the Pintura/Palabra Project— Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art in Conjunction with The Smithsonian Institute and Letras Latinas. Her work has appeared in The Notre Dame Review, The Comstock Review, The Crab Orchard Review, MiPoesias, Lunch Ticket, Diverse Voices Quarterly, The Meadowland Review, The Stonecoast Review, Storyscape Journal, Tigertail, A South Florida Poetry Annual, This Assignment Is So Gay: LGBTIQ Poets on the Art of Teaching, The Lavender Review, and others. She is Editor-In-Chief of Orange Island Review, as well as an English professor at Miami Dade College and a dual-enrollment English instructor for Miami Dade Public Schools in Miami, Florida where she resides with her wife and son.

Eduardo Aparicio, born in Guanabacoa, Cuba, lives in Austin, Texas. He is a writer, translator, and photographer.

Thank you for beautifully sharing your truth, Caridad. I was in emotional suspense as I kept reading, all the way to the end. I hope you and Pepe are emailing each other like crazy. (And you really do look like your mom!) 🙂

Caridad’s writing always draws me in. No contemporary writer is able to grab me the way she does. The last line of this, however, brought tears to my eyes.

Muy bonita historia.