Wishing everyone a belated but heartfelt happy new year! To start our blog posts for 2022, we are glad to feature an important and moving essay by Ana Hebra Flaster, a journalist and writer, who addresses complex topics not always spoken about in our Cuban community. In light of the July 11th protests in Cuba, she writes about growing up in Cuba and her memories of an acto de repudio (act of repudiation) that she remembered from her childhood. This experience haunted her into adulthood, long after the family had resettled in New Hampshire. With honesty and depth, she investigates the history of these actos, in her essay, “A Way Forward,” examining how they have continued into the present in Cuba. Looking to understand the meaning of this painful history, she seeks a community of diverse Cuban Americans in the Boston area, who, as she says, “want to do something constructive as Cuba evolves.” Amid conversations with them and profound self-reflection, she finds a powerful reckoning with the hard topics of our history and also, she finds a new hope. Ana translated her essay herself from English to Spanish, and asked her friend in Havana to double check it. That bridge to and from Cuba also gives us hope. Abrazos, Ruth & Richard

by Ana Hebra Flaster

Read post in Spanish >>

Four generations of the maternal side of our family, summer 1967. Brother, father and mother are in back row (l to r). Grandmother is in middle row, on far right. Her sister-in-law, brother, and father (l to r) never made it out of Cuba. I’m in the middle of front row.

I thought we were playing a game that summer night, in 1967. We were still living in Cuba, in Juanelo, a hardscrabble close-knit barrio, on the outskirts of Havana. My parents had suddenly jumped out of their chairs and began running around, shutting off the lights. When I started to laugh, Abuela clamped her hand over my mouth and dragged my younger brother and me behind the couch. My parents crawled across the floor toward us. Something horrible had brought my mighty parents to their knees. What would it do to me, or Abuela and my brother? The memory of that night has remained diluted and gray, like the light that slipped through the glass blinds of our front windows. But it began to resurface when I was deep into my adulthood and the mother of my own five-year-old daughter, the age I’d been when we left Cuba and settled, almost inexplicably, in New Hampshire. It triggered a greediness for details. I pummeled my family with questions, cross-checked their accounts, found inconsistencies that seemed immaterial to them but felt crucial to me. Only facts could recreate a world I’d lost and now needed to hold in my hand. Sometimes their memories failed them. “Ay, chica,” Tia Silvia said once, “That was about a meelion years ago. Pregúntale a tu mamá.” The memory of the night of the game-that-wasn’t-a-game was different. When I told them what I remembered, they seemed to hold their breath in unison, the same stunned look in their eyes. “That was the beginning of the Six Day War, la guerra de los seis dias,” Papi said, looking at something only he could see. “Fidel had been on the radio, railing against Israel. Revolucionarios marched through the streets after his speeches. They wanted to prove their loyalty.” He stopped for a moment, returned to us. “¡Ñó! ¡Qué susto pasamos!” The look on his face captured the fear he was remembering. We were full-fledged gusanos by then, waiting for our permisos and easy targets for overzealous revolutionaries. And like all “worms”—the government’s term for people trying to leave the country—who were still waiting for exit visas, my parents knew they had to hide as soon as they heard the mob coming down the street. For a long thirty minutes the mob shouted threats and insults. They banged on the cans and pots they carried. A group of them came onto the porch and pounded on our door. Someone broke a window. Shards of glass clattered over the tiled floor. Papi caught a glimpse of a man giving another man a boost in front of our door. They were yanking at a lamp my mother had just bought to cover the bare bulb in the ceiling. My mother pursed her lips at the memory. “I stood in a long line in the heat for that stupid lamp.” Papi grinned. “Do you remember what they shouted? You’re leaving! You don’t need it anyway!” Everyone had a laugh. They were looking for humor in that painful story, as they always did, a tactic I understood by then. Good old Cuban bluster pushed their hurt down, down, down. Until it couldn’t, and the hurt needed tending—or at least acknowledging. The game-that-wasn’t-a-game left a mark on all of us. The sudden fear and shock, the hatred that tore apart what should have been a soft summer night, changed us. What happened to us that night got an official name during the Mariel Crisis in 1980, “actos de repudio.” Whether organized by a neighborhood committee for the defense of the revolution, the Federation of Cuban Women, or some other group, these “acts of repudiation” involved bullying, shaming, and beating up people whose revolutionary zeal didn’t pass muster. They’d been taking place ever since the revolutionary government came to power and had, at a minimum, its tacit approval. But in 1980, the actos grew more severe and routinely violent. Some lasted days, leaving victims blockaded in their homes, their electricity, water, and gas shut off. I’d always thought the actos originated with the 1959 revolution, but Cuban historian Abel Sierra Madero traces their roots back at least to the Machado dictatorship. He says that in those days, “the porra machadista was linked to the disappearances and assassinations of dissidents.” Madero believes the first post-revolutionary revival of this tradition occurred in June of 1959, just six months after Fidel Castro’s new government seized power. The target was Diario de la Marina, a widely read newspaper that had turned against the new regime. By 1960, the paper was permanently shut down.

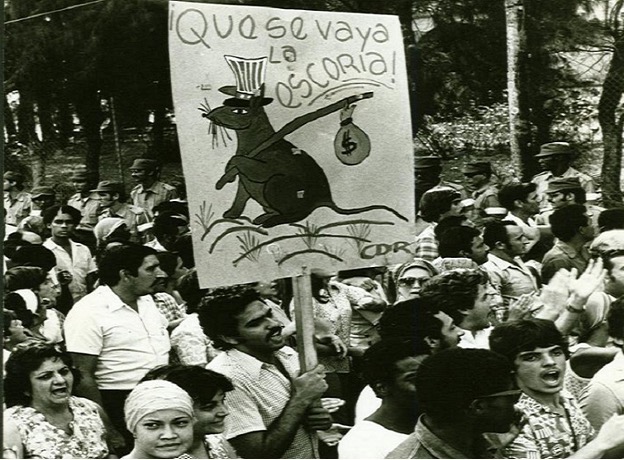

March on 5th Avenue in Havana, in front of the Peruvian embassy, April 1980. Photo: Granma/Fernando Lezcano. Sign: Get out Scum! From article in El Estornudo, by Mario Luis Reyes, 3/22/2021.

Actos de repudio or mítines de repudio, as they are sometimes called, are alive and well. I watched their numbers rise during the artist-led protests in late 2020, again after the July 11th uprising, and more recently when pro-democracy marches were announced for November 15, 2021. But now the actos are targeting new victims, as journalist Mario Luis Reyes points out in a March 2021 article on the history of actos. “Forty years later,” he writes, “the modus operandi is practically identical, except that before, they repudiated those who wanted to emigrate, but now they attack those who want things to change so they can remain in Cuba.” What hasn’t changed, for me, is the fact that each account revives old memories and ignites an enraging sense of powerlessness. I read the reports meticulously, studied the faces in photos and film clips, noted the kids’ tight body language, worried about the grandmothers in the background. Sometimes, the victims shouted back at their assailants, demanding respect for human rights, or appealing for decency. Often, their eyes revealed the fear and shame they were trying to hide behind their anger. In those failed efforts, I saw a vulnerability so complete that the victims seemed almost naked. I felt ashamed for them—and for myself for witnessing it. That may be why I began looking more closely at the other faces, the ones committing the actos. Rage and hatred were front and center, in the shouting, the bulging eyes, flailing arms, the shoves, the kicks, the hair pulling. But sometimes their faces also showed more than they wanted to. I saw traces of reluctance, people who stood back from the crowd, barely chanted, looked down, held their arms stiffly at their sides. There was another story here and, maybe, another kind of victim. What pressures were driving these people? Was it hunger? Their own fear? Had the children in the crowd been taught that this was some kind of fun game? I had looked at those Cubans as the enemy, a vile offshoot of humanity that had sold its soul to an ideology—or for the customary bag of frozen chicken. Now I saw something more troubling. Could they be us? I want to believe that even if I had starving children at home I would never stand on that sidewalk and hurl insults at people who simply thought differently. Seeing the possibility of other answers has weakened my anger, but not the sadness that remains when I read about actos. For me, the essence of Cuban culture has always been a fundamental warmth. I feel it whenever I enter a Cuban home, like a red-orange shawl that wraps around my shoulders—as tangible as the kiss that soon lands on my cheek. Actos smother the source of that Cuban warmth toward others. They destroy a part of Cuban nature that I’ve always known and treasured. That violation is what offends me so deeply whenever I remember that night in 1967 or read about a new acto in 2022.

Act of repudiation after 10,000 Cubans sought asylum at Peruvian embassy in 1980, leading to what became known as the Mariel Crisis. Signs, l to r, read: Out Anti-Socials!; Carter, bastard. Remember Girón (Bay of Pigs); Out Scum!: Photo: ECURED. 10/22/2020, Diario de Cuba.

With another icy New England winter ahead of me, I had decided to pull away from the sadness of that violation and focus on restoring what was lost. This far north, Cubans are rare birds from paradise, but I searched, and I found a group of mostly young Cuban Americans that had somehow found each other in the Boston area and were building a community. They, too, wanted to do something constructive as Cuba struggles to evolve. As I listened to their stories, I heard hints of my own. Yordan, one of the group’s founders, tells one about his abuela, often at the mic during rallies—how she said goodbye to their whole family as they lingered outside José Martí Airport, unable to move toward the door and a new future. “¿Qué esperan?” she scolded, tears in her eyes. They couldn’t have answered her. They had no idea what they were waiting for, why they couldn’t move. “¡Váyanse! Pa’lante. Ya!” She was almost shouting. “Go, all of you. Get going! Enough!” Yordan never saw her again, so he resurrects her for us almost every time we meet, somehow binding together this very mixed group of Cubans. Some are the children or grandchildren of Cubans. Others came during Mariel. Some by plane and some on rafts. There are Republicans, Democrats, and people who shut down or rev up when things get political. One day, a woman prayed for Cuba openly while others in the group looked on uncomfortably. A few people are clearly well-off and others more working class. There are young and old, black, and brown and white. One man uses a tricked-out wheelchair to get around. They kiss when they see each other and debate the best way to roast a pig in the snow.

Screen shot of act of repudiation against independent journalist, Iliana Hernandez, December 8, 2020, Cojímar, Cuba.

With so much diversity, I wondered if any of them had been involved in actos. I scanned the faces of my fellow Cubans during my first rally with them at the State House in Boston. Were any of them chanting Cuba Libre in freezing weather as penance for old sins? I knew that some of the older Cubans had probably participated in actos as students during the Mariel and ’94 balsero crises. In those days—and even now—students were taken directly from their schools to actos. But our group had only been together a few months, and I was one of the newer members. I might be wondering, but I was far from asking. So, I shook off those thoughts and started to help one of the older women with the fliers we’d be handing out. Xiomara was shivering—and she was cranky. “Mira como tienen a mi bandera, arrastrada por el piso,” she said, angry that the Cuban flag we’d hung up on the portable gazebo was grazing the sidewalk. I tried to distract her by asking her about her Cuban life, but that got her angrier. “Xiomara!” A smiling young woman was approaching fast with an older man in tow. She introduced everyone and pulled me away once Xiomara and her new friend started talking. “She can be un poquito quejona,” she said, “but she’s great once she settles in. I’m Elena, let’s get some signs.” Near the pile of pickets, a tall black woman was looking for a place to put her Fendi purse. She finally tossed the polished leather bag on a pile of backpacks and began sorting through the posters. “Este sí que está bueno,” she said turning to face us. She held a poster with a nasty message about dictatorships in her neatly gloved hands. “¡Viva Cuba!” she shouted, smiling, one hand on the picket, the other extended in front of her. “Sonya.” I couldn’t imagine Sonya or any of the others taking part in an acto. But I still needed to understand why people choose to participate in them and what that choice does to a person over time. The testimonies of Cubans who took part in actos are giving me answers to both questions. Maria del Carmen, who still lives in Cuba, was fifteen in 1980, when the Mariel crisis began. One morning, the principal came into the classroom and ordered everyone to conduct an acto at the house of a teacher who was trying to get out of the country. Forty years later, she still remembers the insults they chanted that day. “The whole institute was there…I don’t remember throwing eggs, because we’d come directly from school so we didn’t have any. For us it was just a diversion…I didn’t understand…I thought the teacher was betraying the country.” But as Maria Del Carmen matured, she began to see the violence and injustice of the actos. “I began to feel a profound shame and I promised myself that I would never for any reason participate or support such abuse.” So at least for some people participating in actos left a mark, changed them forever. Acclaimed Cuban artist Erik Ravelo confirms it. He was in sixth grade when his teacher took the entire class to participate in an acto. They chanted insults as an elderly woman, the mother of a dissident, was beaten in front of them. “I’ll never forget such a barbarous event. Never. They split her face with a construction helmet. They smashed her glasses. She was bleeding when they pulled her from the enraged mob and put her in a patrol car. And they took her away.” Ravelo, who no longer lives in Cuba, has used his art to denounce actos, which he calls “one of the ugliest, lowest and most inhuman pages” in Cuban history. In Doctrina, his photographic work on the subject, he criticizes the use of children in actos. Ravelo was moved by the reactions of other Cubans to Doctrina’s powerful image. One wrote, “I was that child.” Ravelo’s response shows his shared sense of guilt with the viewer—and a reach for forgiveness. “Sí, tigre,” he wrote back, “a disgraceful fate made all of us that child.” Were any of my new Cuban friends that child? Were any of them like the child I was, inside the house under assault? Maybe my new friends have already told me all I need to know about them through their current actions. I’ve seen them working to reclaim something precious that was taken from them—or that they may have squandered, in their confusion or out of fear. In this cold New England, they’re reaching for people who speak the fundamental warmth of our culture. It’s a warmth I felt recently, when the topic of actos came up after someone reported one that had turned violent. A woman in the group began describing an acto she’d endured years ago. As she neared the end, she cracked a smile and pulled a funny detail out of her story. Just like my family used to. Those sudden sparks of familiarity keep us reaching for each other. And that tells me these people want to do the right thing now, to make things better back home—and in the new one we’ve all been building. These are the actions I’ll look for right now. Positive, constructive, forgiving. A way forward.

Cuban Americans protesting Cuban human rights abuses. Massachusetts State House, Boston, 11/14/2021. Photo: Ana Hebra Flaster.

Ana Hebra Flaster was five years old when her family fled post-revolutionary Cuba in 1967. She strives to honor the immigrant experience and Cuban American culture through her writing and storytelling, which have been featured on national broadcasts of NPR’s All Things Considered, PBS’s Stories from the Stage, and in national publications, including like The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and The Boston Globe. Her work has been selected for anthologies such as Alone Together: Love, Grief and Comfort in the Time of COVID-19, winner of the 2021 Washington State Book Award for Nonfiction. She is often invited to speak with high school students, in classroom and schoolwide settings, about writing, Cuba and the immigrant experience. Ana’s forthcoming memoir, Radio Big Mouth, explores her family’s journey from disillusioned revolutionaries in a working-class Havana barrio to stunned refugees in a snowy New Hampshire mill town. www.anacubana.com Twitter @AnaHebraFlaster

Gracias Anita.

Artículo necesario para reflexionar sobre algo que nos toca a muchos, desde varios ángulos.

De niños, mi y hermano y yo, ambos con no más de 10 años, vivimos un acto de repudio frente a la casa de una vecina que se iba con su hija por el Mariel. Fue durante la tarde-noche. Vinieron a buscarnos y, aunque mi madre no nos dejó participar, la bulla era justo al lado de nuestra casa. Hubo consignas y cantos que en mi mente infantil no significaban demasiado; sin embargo, el sonido de los huevos impactando contra la pared me llamó mucho la atención.

Varios años después que madre e hija se fueron, la abuela que quedó en casa no había quitado aún las manchas de huevo de la fachada. Ellas permanecieron allí, momificadas y firmes, como recordándonos aquella extraña noche…

Nosotros fuimos testigo. Aunque no participamos, sí lo vivimos tan intensamente, que el recuerdo permanece muy nítido, así como las manchas de huevo sobre la pared bien frescas en mi memoria.

Muy buen escrito.

Espero por el siguiente.

Ana I remember when you and your family arrived in our little neighborhood with your cousins. Loved see you article

Ana I remember when you moved to our neighborhood with your cousins