Cuba and Cubans are continually being represented in visual images and consumed through visual images. However, too many of these images have become repetitive stereotypes. It was therefore a welcome surprise to discover the photographs of Geandy Pavón. There is something very unique about his representation of Cubans. He creates images of Cubans that are solemn, humble, and haunted. Whether photographing the Cuban exile community in West New York, New Jersey, which he knows intimately, or the Cuban migrants who until recently were stuck in camps in Nicaragua, he strives to offer another way of seeing Cubans that cracks through the surface to capture the soul of a people leaving home, finding home, or still searching for it. We are delighted to feature Geandy Pavón’s photoessay as our post for July and hope you will also be captivated by his work. Abrazos, Ruth and Richard

Read post in Spanish >>

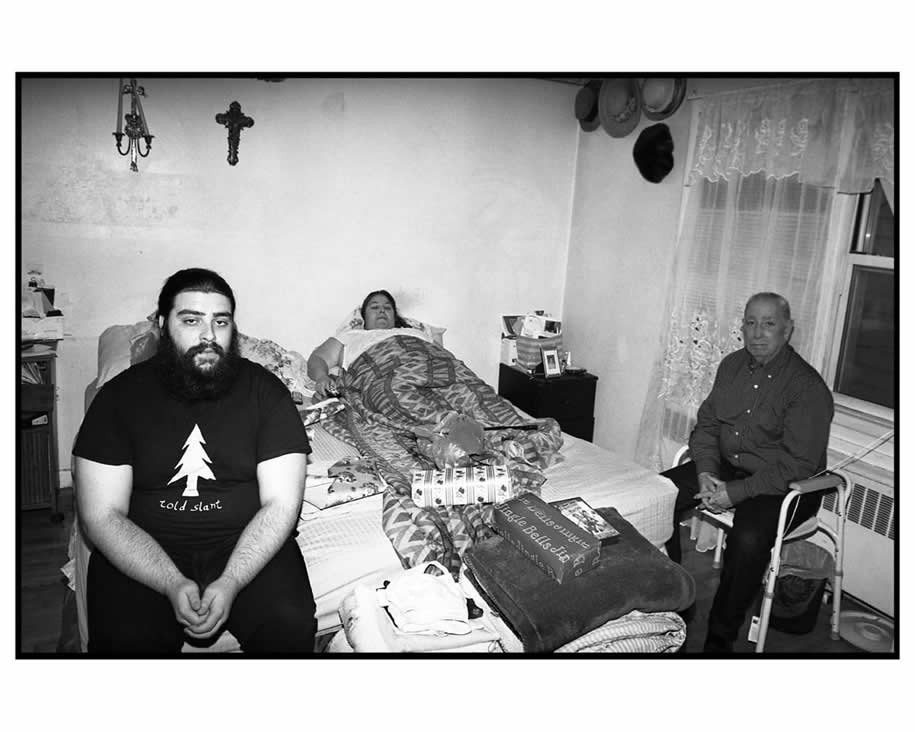

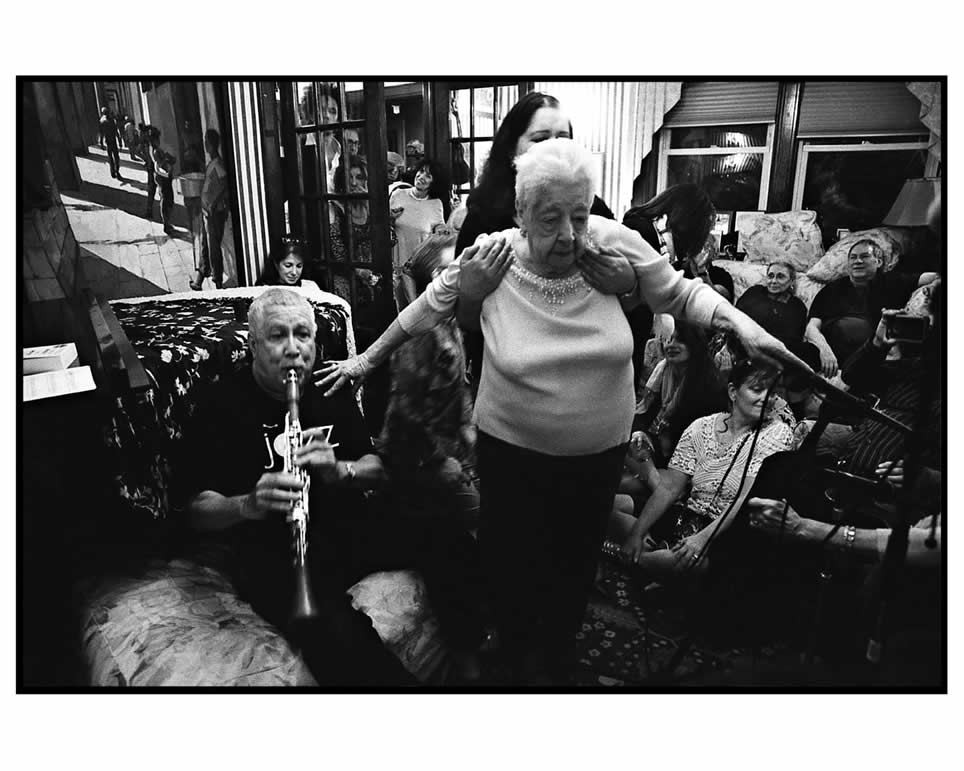

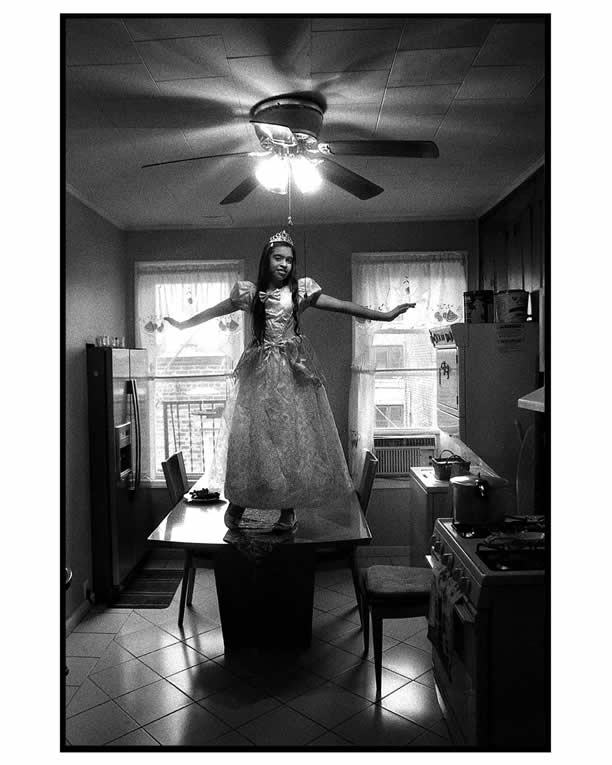

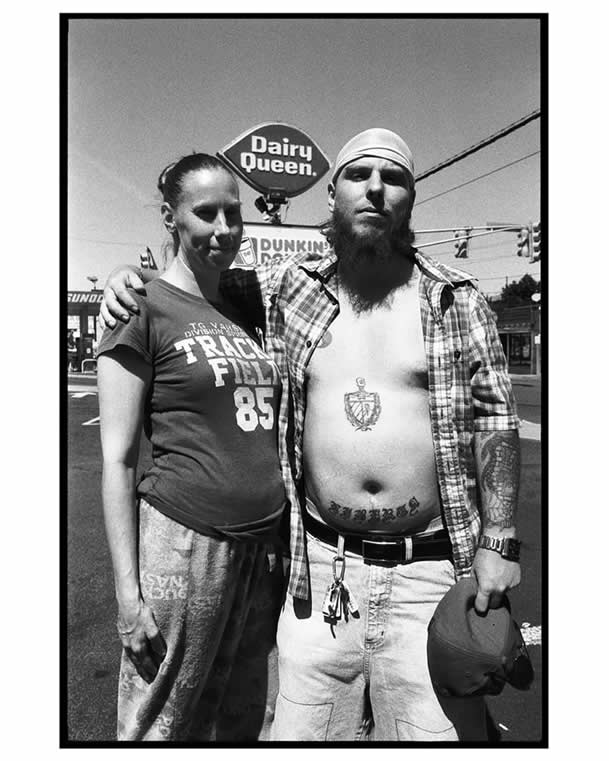

Geandy Pavón was born in 1974 in a neighborhood in the eastern region of Cuba, in the Las Tunas province. There he began studying fine arts at the local academy. Later he moved to Havana and continued his studies at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas, graduating in 1994. Two years later, amid one of the worst economic crises in Cuba, he immigrated to the United States with his parents and younger brother. The family settled in the New Jersey town of West New York, the second largest enclave of the Cuban diaspora in the U.S. Surprisingly, photography was not a part of Pavón’s training in the visual arts, which focused his attention on painting and video art. He encountered photography later, when he began using photographic images as a reference for his work and as a visual record of political and historical material. His life as a photographer began when he met Juan Carlos Alom, a teacher of Cuban photography. Alom introduced him to the world of analogic film photography, and together they built a small lab for printing and developing film. Pavón continued embracing photography not just as a form of expression, but also as a way of seeing and living life. He notes, “Through photography I enter a state of consciousness of the world around me. I notice the existence of stories rarely told, at least photographically. Like the story of Cubans outside of Cuba—that rare mix of snow and Cuban flags in gardens, the forced adaptation of one world within another, Spanish with an American-English accent, English with a Cuban accent, neighborhoods, restaurants, interiors, basements, monuments to Martí.” The documentation of that ephemeral Cuban world outside Cuba obsesses him and is at the forefront of his work. This obsession is evident in Vae Victis, a documentary photography series that portrays the life of a group of Cubans who were political prisoners in the 1960s and 1970s, and who still gather every Tuesday in the heart of Union City in New Jersey. Pavón’s most recent series, Quo Vadis Cuba, portrays life at three Cuban refugee camps in a town called La Cruz on the border of Costa Rica and Nicaragua, where he lived among the refugees in 2015. The camps were a consequence of the Nicaraguan government’s refusal to allow Cuban immigrants to travel through Nicaragua to the United States. More than 8,000 Cubans were stranded—the most significant Cuban immigrant crisis since the Mariel exodus of 1980 and the raft exodus of 1994. Thinking about how Cuba is represented in photography immediately conjures up epic images of the triumph of the revolution in 1959, or the already classic postcards of American cars from the 1950s sputtering among Havana’s ruins. Likewise, images of the diaspora or exile communities are too often reflected in a facile and simplistic way. Yet the people of these communities embody, beyond the stereotypes, all the complexities of the human condition. Pavón’s series-in-progress, The Cuban-Americans, intends to capture those complexities by concentrating attention on what Pavón thinks of as the pure space of being—the oasis amid the ordinary places where the people of these communities live out their lives. In The Cuban-Americans, Pavón echoes the work of Robert Frank, a Swiss-North American photographer. Specifically, it is Frank’s series The Americans that interests him, for the way it refutes, in Pavón’s view, the antiseptic discourse of America in the 1950s. Instead, Frank portrays Americans as torn between optimism and the reality of impoverishment and racial clashes. Similarly, The Cuban-Americans escapes the triumphalist and chauvinistic discourse often promoted in exile, as well as used in the propaganda of the Cuban government and its caricatured images of exiles. Refreshingly, the exiles Pavón portrays are not epitomes of economic success or former landowners who resent the revolution. As Pavón explains, “These are portraits of friends, family, people I meet in the streets of the Cuban neighborhoods in New Jersey—Union City, Guttenberg, West New York and North Bergen—”the Cuban ghetto,” as I like to call it. That’s where all the portraits were taken.” Portraits, as Pavón notes, “of normal people who rejoice and suffer in exile and live in the hyphen between, as the Cuban-American writer Gustavo Perez Firmat puts it.” Pavón is planning to visit Miami soon to expand the series. He’ll concentrate primarily on a Cuban mobile home community in Hialeah. Pavón’s images are not simple testimonies; they wield an aesthetic influence of great importance. In addition to Robert Frank, in Pavón we encounter profound references to the photographic work of Diane Arbus and Mary Ellen Mark. And there is a strong influence from the visual arts, especially Velazquez, Caravaggio and Georges de La Tour. But Pavón’s work offers more than a conversation about technique or influence; like all art in conversation with identities and communities, it offers a new way of seeing. EXILE FAMILY

The people portrayed in this photo are Alfred (the young man with the beard), Evaristo, and Silvia. I’ve known this family since I arrived as a refugee to the U.S. in 1996. Evaristo was a political prisoner when he was 17 years old. He has dedicated his whole life in exile to the fight for a change in Cuba’s government, a change which hasn’t arrived and around which they have structured their lives, their family life as well as their social lives. Cuba has been the center of this family’s life, including for Alfredo, who was born in northern New Jersey. Silvia is currently suffering from a nervous ailment and spends almost every day secluded in bed. Evaristo is the only breadwinner of the family.

THREE TIMES FIVE

A birthday party for triplets Malcolm, Leandro, and Salvador. All three are wearing quinceañera crowns as a joke–that day they turned 15 years old. For Cubans, the grand fifteenth birthday celebration is always a party celebrated for females but not for males

LATIN JAZZ

This is a typical scene from jam sessions at the house of famous Cuban-American jazz musician Paquito De Rivera. Paquito is playing the clarinet in this photo. The woman in the center is Nelsa Márquez, the legendary singer of the las Hermanas Márquez duo, a relic of the musical splendor of Cuba in the 50s.

CUBAN AMERICAN PRINCESS

A portrait of my daughter, Alicia. She is posing on top of her grandmother’s kitchen table, dressed in her Halloween costume.

LA PURA

A portrait of Carlina Zayas, my mother.

CUBAN REDNECKS

I was driving when I saw this couple walking near a Dairy Queen in North Bergen, New Jersey. I approached them to ask their permission to take a photo. They spoke intermittent English with a strong accent, and although I spoke to them in Spanish, they insisted on speaking English. I don’t remember their names. I returned a few times to ask for their address and to give them a copy of the photograph, but I never saw them again.

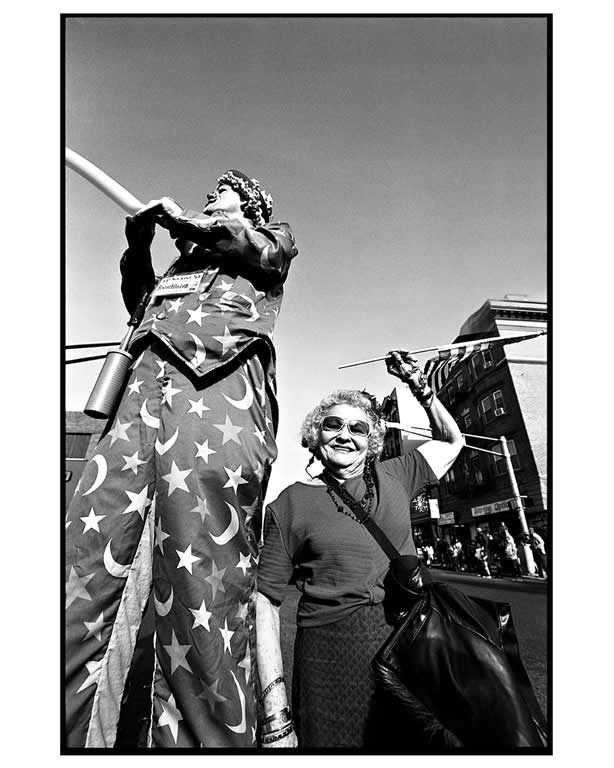

PARADE

A Cuban Parade in Bergenline Avenue, West New York, the heart of the Cuban community in New Jersey. Every year the Cuban Diaspora in West New York celebrates the Cuban Independence from Spain—after the Spanish-American War, Cuba gained formal independence from the United States on May 20, 1902. Bergenline Avenue is one the largest commercial streets in United States, and most residents and storeowners are of Cuban descent.

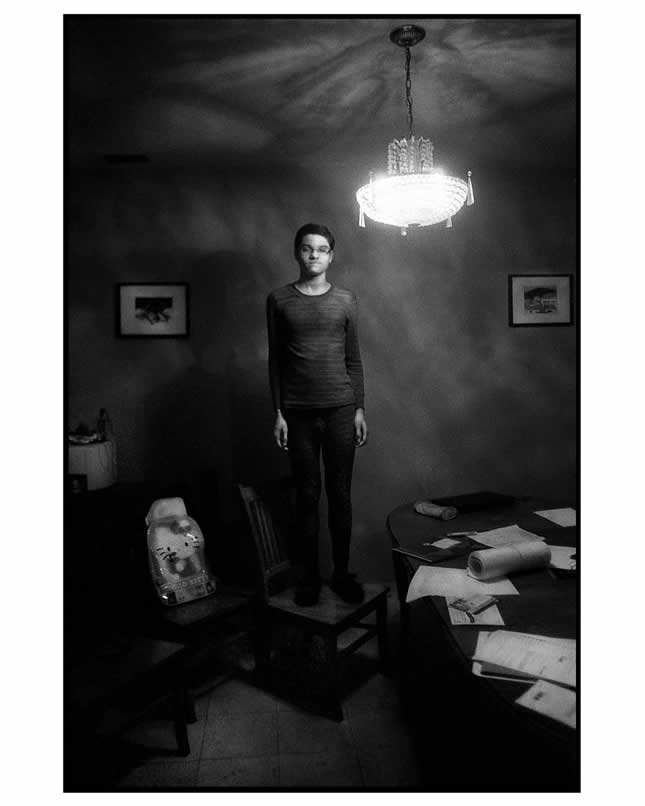

HELLO KITTY

Eric Del Risco es un adolescente ensimismado e inteligente, hijo del escritor exiliado Enrique Del Risco y la profesora Eida del Risco. A Eric lo conozco desde apenas unas horas de nacido, siempre me llamó la atención su personalidad, es un ser que no tiene la capacidad de poder mentir. Eric vive en West New York, NJ con sus padres y su hermana Lila, su casa es un centro de encuentro de varios intelectuales, artistas y activistas políticos en el exilio.

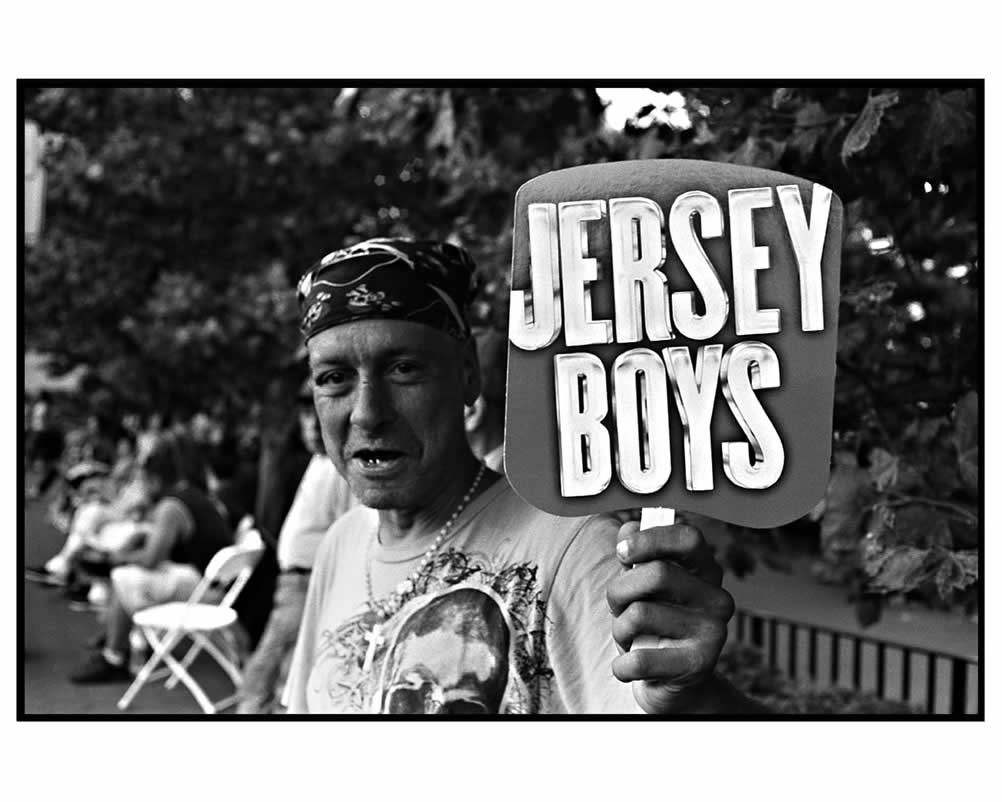

JERSEY BOYS

I have forgotten the subject’s name. I remember he came during the migratory crisis of “el Mariel” in the 80s. I also know that he likes the fact that when people approach him, they always speak to him in English. According to him, that means that he looks “American.” Every time I see him he is drunk.

Eduardo Aparicio, translator of Geandy Pavón’s piece, was born in Guanabacoa, Cuba and lives in Austin, Texas. He is a writer, translator, and photographer.

I am always impressed by the beautifully written postings that appear in this blog. I relate to all of them as they touch my wounded Cuban soul.

I am not as artistic nor as good a writer as those that post. But I believe that I have discovered how to, finally, bring economic and political reform to Cuba. And it won’t cost a single taxpayer penny.

There is one person who is responsible for maintaining the Cuban Embargo. Her name is Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, the Florida 27th District Congresswoman.

She has betrayed the Cuban-American community and, worse, the American People.

I know that this is a serious charge, but I am willing to debate her in public.

I travel to Cuba, I install water purification systems in Cuban churches, free of charge through volunteers and private donations. I have first hand knowledge of the economic and political situation in Cuba.

There is no spirit of communist revolution in Cuba. The Cuban people want a better economy, Internet, freedom to worship and more liberty.

The only claim to legitimacy that the Castro regime has is that he is protecting the Cuban people against the Cuban Embargo.

You take the Cuban Embargo away and political and economic reform will follow.

You defeat Ileana in the November election and the Cuban Embargo legislation will be defeated in the US Congress.