Hola Reader-Friends:

Twenty years ago, Ruth Behar (my friend, colleague, mentor, and co-creator of this blog), edited Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba, a landmark anthology that brought together Cuban voices of the second generation, both on the island and in the diaspora, for the first time in English. The multi-vocal and multi-genre collection includes both scholarly and creative writing and visual arts by Cuban and Cuban-American writers and artists that celebrate the informal networks that Cubans in both countries have maintained through artistic, academic, family, and other ties. On a personal note, the book changed my life, inspiring me to start building my own emotional bridge through poetry across time and place toward my Cuban heritage and identity. Still considered one of the most important works on the subject, and more timely than ever, the 20th Anniversary edition of the book will be re-issued this year with a new foreword. To celebrate, we present here a conversation with Ruth about the anthology. It will also be part of our conversation at the Miami Book Fair on November 21, as part of a panel on this blog, which was largely inspired by Ruth’s brilliant bridge-building work.

Abrazos,

Richard Blanco

Read post in Spanish >>

Havana (Gabriel Frye-Behar)

Richard: When I pause to think that this anthology was first published twenty years ago, I stand in awe of the courage it must have taken to develop and launch such a landmark project back then. What was the political and emotional climate at the time, and how did that climate challenge you personally and/or motivate and inspire you? How was the book received?

Ruth: I am not so sure whether it took courage to develop and launch Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba, though thanks for thinking so. Looking back, I’d say I went into the project with a lot of hope and a lot of innocence as well. Some would say I was naïve. It was the early 1990s. Cuba’s economy hit rock bottom after the collapse of the Soviet Union. It was a time of desperation, hunger, blackouts, and uncertainty, and there was the vast departure of balseros taking to the sea in 1994. The spirit of that era was very melancholy. An entire social system was crumbling. Cuba was transitioning toward an economy and a culture based in tourism and remittances from Cubans abroad. Yet people were still trying to hold on to tarnished revolutionary ideals and to their dignity. They were also moving to a new way of life centered on being able to inventar and resolver, inventing unusual solutions to everyday problems as the socialist safety net fell apart.

Entering this surreal context, I was a nervous wreck. Eager to learn about life in Cuba, I was also terrified of the catastrophes I might experience while there. My parents had filled me with fears. I went through a period where I seemed to be reliving the trauma of having left Cuba as a child. I had wrenching panic attacks and would weep suddenly and for no reason. But I got over my fears as I met a wide range of people on the island—from my former nanny and our old neighbors in Havana to writers, thinkers, and artists of my generation who were eager to talk and make up for lost time. I had expected to be seen as a gusana, a “worm” of the Revolution, and to be rejected by my counterparts on the island. Instead, there was an openness toward those of us who left and came back in search of memory, in search of the parallel life we might have lived had we stayed. I was welcomed and told I belonged, told I was still a part of Cuba.

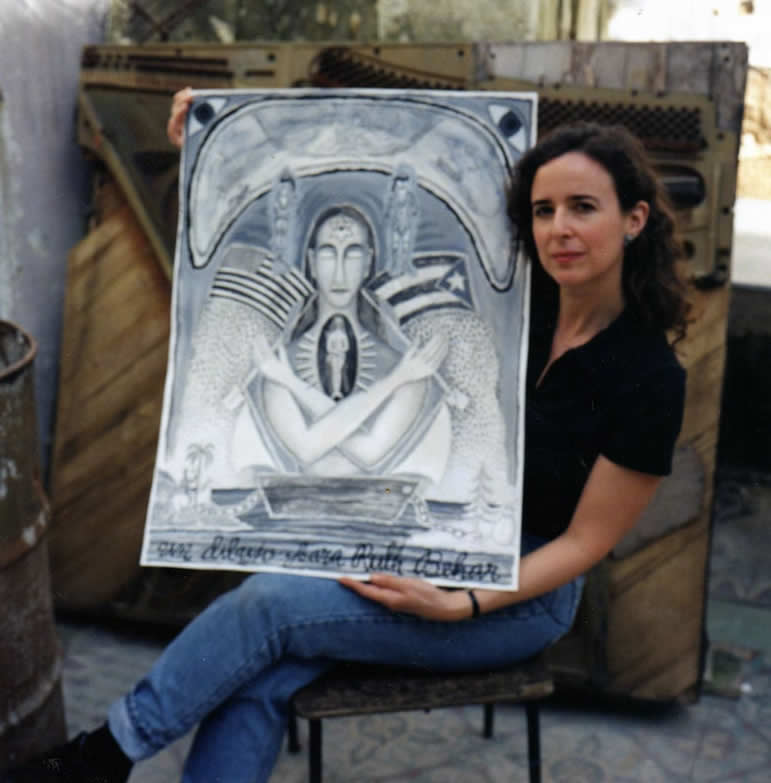

Ruth on one of her first trips to Cuba with artwork by Rolando Estévez (Rolando Estévez)

That changed my life. I began to go back and forth between the island and Michigan every few months. Then I heard about other Cuban-Americans who had gone through similar experiences but hadn’t yet spoken out, because it was still a moment in the United States, and especially in Miami, when you didn’t announce en voz alta that you were traveling to Cuba. It occurred to me that something needed to be done to bring these voices together, to form a bridge between Cubans on the island and in the diaspora. The term “diaspora” had not yet been used to talk about Cubans abroad. We had called ourselves “exiles” until then. But we had stayed in the U.S. longer than we had expected and become a Cuba outside Cuba, a nation outside a nation, which is what a “diaspora” is. The island and the diaspora had been separated by ideology and politics. I thought I could bring about national unity and a vision of peace with an anthology seeking bridges. As I said, I was hopeful and innocent!

There were a few who criticized me for being too romantic, but overall the book was received very well, both in Cuba and by the Cuban diaspora. Afterwards many people picked up on the concept of “bridges,” or “puentes,” when speaking of ties between Cuba and Cuban-Americans and Cuba and the United States. It was the first book of its kind, and it made an impact. It became mainstreamed to the point that not everyone realized when they were referencing it.

Richard: How do those circumstances compare to the present day, especially given the recent restoration of a diplomatic relationship between the U.S. and Cuba? How is the book still relevant?

Ruth: Two decades later, Cuba now has a greatly expanded tourist economy, two billion dollars yearly in remittances, and an expanding private sector that is providing new opportunities for some Cubans. Travel restrictions have been eased in Cuba and it is now easier for Cubans to spend time abroad—as long as two years—without losing their homes and possessions on the island. But there are many Cubans who feel they are being left behind and they have grown desperate. They are taking to the sea, rushing to set foot on American soil and request asylum, afraid that the fast lane toward U.S. citizenship that became the privilege of Cubans after the Revolution will soon vanish as the two countries renegotiate their relationship. As this complex situation unfolds, there is now a crazy race among Americans eager to get to Cuba “before it changes.” All the Americans who were on the fence about traveling to Cuba now feel they have permission to go, and they are flocking to the island to see this once-forbidden place and also to check out investment options. The bridge to Cuba is now heavy with travelers going back and forth, and those who can’t get on the bridge are trying to float across the ocean, praying they’ll make it to the other side.

Apartment building in Havana (Gabriel Frye-Behar)

Is the book still relevant in this current situation? I think it is very relevant. Twenty years ago, my anthology offered a forum for people to reflect on the meaning of bridges via poems that explored common hopes and memories shared by all Cubans, via essays by Cuban-Americans who wrote about the emotional journey of returning to Cuba, and via stories that sought to explore the meaning of Cuban identity, both by those who’d never gone back to Cuba and those who’d never left the island. The issues of twenty years ago are vital today. Many more of us are now thinking about the bridge to and from Cuba and trying to figure out how to make it sturdy and lasting, so that deeper conversations can be had, more meaningful exchanges forged, and dreams fulfilled.

Richard: What was your reasoning for including “from Cuba” in the title of this blog, instead of only “to Cuba,” as in the title of the anthology? What does the proverbial use of the word “bridge” ultimately mean for you in the context of the anthology? What effect did you hope Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba would have twenty years ago, and how does that compare to your hopes today? What role do you think literature and the arts can play in this kind of bridge-building?

Ruth: When you and I decided to create our blog, it seemed to me it was time to acknowledge that the bridge now went in both directions—to Cuba and from Cuba. Twenty years ago, it was more difficult for Cubans on the island to travel abroad and so the bridge mainly went in one direction. That was a moment when Cuban-Americans in large numbers, especially scholars, writers, and artists, were beginning to go back to Cuba on a regular basis, seeking to normalize their personal relationships to the island. I wanted to emphasize those return journeys in Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba, and also to legitimize them, to let the world know there were Cuban-Americans who were advocates for establishing a real, vital, complex, and often ambivalent connection to their homeland. I was careful to include several Cuban-American contributors who had never returned to Cuba, and did not wish to go back, but who still felt a bond to Cuba and had created a bridge through their writing and scholarship. The “bridge” worked as a symbol not only for those who were physically going back and reclaiming their relationship to the island, but also for those in the diaspora who traveled to the island metaphorically through their devotion to Cuban culture, literature, and art, and most of all, through a fundamental belief that their Cubanness couldn’t be taken away from them, no matter how much time had passed since they or their families had left the island. There was also, however, the “bridge” from the island to the diaspora, and in stories, poetry, and art, you could see that those who had stayed had never forgotten those of us who’d left, that we were still present in their imagination.

My hope twenty years ago was to create awareness of how these bridges crisscrossed among Cubans and to show that despite the wounds caused by decades of antagonism between Cubans on the island and in the diaspora, there was a common memory and culture that we shared. At the same time, I never sought to make light of the fact that there were real ideological differences between us as Cubans that had split us as a people. In many ways, the Revolution was a civil war, like the Spanish Civil War. Those of us who were children of the Revolution had inherited this division and grown up within it. But as adults we wanted to know what tied us together as a people, and Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba was about that search. I had a deep faith that, to quote our beloved José Martí, los libros sirven para cerrar las heridas que las armas abren—that books could heal the wounds opened by weapons. Literature and the arts offer spaces to imagine other worlds, to tell the truth on a human scale and show how particular individuals live their lives and make difficult choices. Through story, metaphor, image, I feel that the writers and artists in the book were able to look beyond the surface divisions and offer more subtle and nuanced insights into our culture as Cubans.

Malecón (Ruth Behar)

Richard: What are some of the most powerful pieces in the anthology and/or some of the more interesting backstories about some of the pieces? Did you forge any life-changing friendships or relationships as a result of your editorial work on the anthology?

Ruth: I wish I could speak about every piece in the anthology. There is a story behind every single one and they are all special to me. So before I say anything more, I want to thank all the contributors for being a part of the project, for trusting me with their work, and believing in the idea of bridges.

Because space is limited, I will mention just one of the pieces that is extremely powerful: Raquel (Kaki) Mendieta’s piece, “Silhouette,” about her cousin, Ana Mendieta, who was the first Cuban-American artist to go back to Cuba, where she created works in the soil, sand, and caves of the island, works that would ultimately disappear, leaving no traces, a metaphor for her own departure from the island. Kaki wrote with a blunt awareness of the distance that had grown between them and the love they sought to find during their reunion in Cuba. Kaki addressed her artist-cousin in this way, “You came with your Art, and we waited for you in the lobby of the hotel.” In conclusion she referred to Ana’s tragic death in 1985, in a fall from a 34th story apartment in New York City, likening it to the silhouettes Ana had made, using her own body traced onto land, fire, and as flower blossoms floating down a river. Ana’s final silhouette, as Kaki put it, was “carved, forever indelibly, into a New York street.”

Kaki was one of the people in Cuba to whom I’d extended my bridge and it was very moving to include her piece in Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba. I had never expected that she would leave Cuba, but in 1994 she came to the conference at the University of Michigan that I organized to launch the anthology and overstayed her visa, choosing to remain on the other side. She seemed eager to reinvent herself in the U.S. But sadly she could not, and she ended her life in 1999. I tell this story in more detail in a subsequent anthology, The Portable Island: Cubans at Home in the World, co-edited with Lucía Suárez. That’s the anthology for which you, Richard, wrote a beautiful piece, “Wherever That May Be,” about the search for home. There were also several contributors to Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba who wrote sequels to their pieces in The Portable Island. But Kaki’s story was, for me, the sad aspect of the bridge—the story of the bridge that failed, the bridge that collapsed into the sea. I want to honor her memory here as we speak of the more hopeful facets of bridges.

In response to your other question, yes, I did form many life-changing friendships as a result of my editorial work on the anthology. To talk about all of these friendships would take pages and pages, probably an entire book. I will just mention my long friendship with the book artist Rolando Estévez, whom I first met twenty years ago. He and I immediately felt like mirrors of each other. At the age of fifteen, he had been left behind in Cuba by his parents and younger sister, who resettled in Miami. I had been taken out of Cuba as a child, too young to make my own decision about where I belonged. Our shared sense of rupture created a strong bond, as did our love of literature and art. Through his stunning handmade books, Estévez introduced me to the classics of Cuban literature, and in particular, his love for poetry helped me find my way back to a form I had adored as a young woman and abandoned when I became an anthropologist. His ability to construct such beautiful symmetries between word and image continues to amaze me. He created the artwork for the cover of the 20th anniversary edition of Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba and also made lovely images for our blog.

Richard: How does your work as an anthropologist, ethnographer, and writer interact with your work on this anthology? How do you navigate between the artistic, scholarly, and political lines that tend to blur for us as Cuban-American children of exiles? What are some of those challenges, and have you been able to overcome them?

Ruth: I think of Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba as a project in which all of my identities and all of my passions came together. Classically, anthropologists work with exotic others in distant lands or with those considered less privileged in order to bring their voices to the attention of the world. For the Bridges project, I was working with those who shared a common culture with me, and I was going back to the place I had called home and wanted to call home again. I was engaging in what I later came to call diasporic ethnography. I was starting out as a professor of anthropology, but I spoke as a poet and a memoirist in the anthology, daring to view myself as a creative artist, or an anthropoeta. I encouraged other scholars to do the same, to write personally and poetically, and to question the academic writing we had been trained to do. That is why several of the scholars, including Nena Torres, Flavio Risech, Ester Shapiro, and Alan West, went out on a limb with more personal pieces than they were accustomed to writing.

But as you say, for so many of us who are Cuban-American children of exiles, the lines between the artistic, scholarly, and political approaches do blur. We grew up hearing the political talk and wondering who was right and who was wrong. We had to go in search of some understanding of the facts through reading history books and other scholarship. And we had to find a way to transmogrify what we heard, what we read, and what we felt by writing poems, or making art, or telling stories.

Cine Yara, Vedado, Habana (Ruth Behar)

The main challenge I’ve experienced in my career is trying to be loyal to one genre—which, as an anthropologist, would mean I’d be expected to write only ethnography my entire life. But I wanted the freedom to write in a variety of genres. I sought to overcome that limitation in Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba by creating a space for a very broad mix of poems, stories, testimonies, plays, essays, conversations, critiques, mambos, reviews, manifestos, and even including an ode to Cubans and airports by historian Teofilo Ruiz. The art is also extremely varied and includes painting, installations, sculptural work, and pieces that invoke a strong Santería aesthetic. I wanted the anthology to be a great big mosaic of voices and visions, as energetic, diverse, and unstoppably creative as Cuba itself.

Richard: In the process of working on the anthology, I imagine you must have had some powerful political, personal, and cultural revelations. How did this project change your life when you first worked on it? And now, as you look over it again twenty years later?

Ruth: It was hard to put the anthology together. The internet was in its infancy, so we were still using regular mail in the U.S. And communication with Cuba was nearly impossible. Phone calls were expensive and unreliable. Gathering writing and art from Cuba was a challenge, though many wanted to participate, and people often gave me the only copy they had of a manuscript or a slide. In his poem, “Epistle to Jose Luis Ferrer (From Havana to Miami),” addressing a friend who had recently left the island, Jorge Luis Arcos wrote, “Diaspora, like death, interrupts all conversation.” At that time there was no email, no quick and inexpensive way to be in touch with those who had crossed to the other side. One of the revelations for me was how the power of politics had divided us as a people, turning the ocean into our Berlin Wall, creating barriers for communication between those who stayed and those who left; indeed, interrupting all conversation.

The anthology is filled with personal stories. These stories came from the heart, and they revealed the sorrow and grief that was brought about by the splitting apart of the nation of Cuba. But there is also a great desire to heal and to find spiritual closure. You see that in so many of the pieces; for example, Rosa Lowinger speaks about architectural conservation in Cuba as a way to repair things that are broken, including her relationship with the island. Or in the beautiful photo/text project that Eduardo Aparicio put together, “Fragments from Cuban Narratives,” he shows Cubans on both sides of the border trying to make peace with where they ended up. An important lesson for me was that through the personal voice you could get at a level of understanding that went beyond the polarization of politics and unearthed a deeper truth. I became committed to writing in the personal voice—something I had just begun—through working on the anthology.

Now, twenty years later, I am in awe that so many talented and brilliant people came together to lend their voice to a project that was incredibly utopian at a time when many utopian dreams were falling by the wayside.

Grand Theater of Havana (Ruth Behar)

Richard: What broader or universal message does the anthology echo for readers outside of the Cuban diaspora or the Cuban people of the island?

Ruth: There are many diasporas all over the world. This means that numerous people are living outside the territory where they were born, but still holding on to the culture of the place they no longer physically live in. Mentally and emotionally they inhabit that abandoned place. They can’t quite let go of it. The desire to create bridges to a homeland can be felt by all who have been uprooted, whether by force or choice. We also know that people in various homelands hold on to the memory of those who left, as they do in Cuba. Bridges to Cuba/Puentes a Cuba speaks to that deep relationship between homelands and their diasporas. The anthology is also about border-crossings and the importance of trying to create bonds of hope in tense and politically polarized situations. I think these universal themes resonate with many people, even readers who aren’t as obsessed with Cuba as you and me.

Diaspora child. Thanks for this. I guess i can finally walk this ramified bridge to identity.

I am SO HAPPY to learn about the new edition of Bridges to Cuba! Congratulations, Ruth, and THANK YOU! I will be recommending it to anyone who wants to learn more about Cuba through literature…