As we near the end of the summer, we are thrilled to feature as our August blog post a stunning and evocative piece by Achy Obejas that defies description and is both moving and profound. Part prose-poem, part tango dance, part intertextual game, “Volver” asks us to reflect on the way we speak and think about our complex relationships with Cuba. Teasing and thoughtful, Achy leaves us wondering how our words, among them those of Martí and Obama, and others, have come to represent and misrepresent the island we want so much to understand. We hope you enjoy the piece as much as we did and look forward to your comments!

Abrazos,

Ruth and Richard

By Achy Obejas

You are returning, you are going back to where it all began, careful to engage the necessary oblivion of the circumstances that took you away in the first place. You will hold your breath and pretend enough answers have been provided to satisfy your pride, your urge to be here, on the threshold of what might have been home if not for upheaval, if not for the price of sugar and oil on the world market, if not for the assurance of safety and comfort elsewhere, if not for revolution and exile.

Y aunque no quise el regreso, siempre se vuelve.

Here is the sea, the jeweled sea, flickering with caution. The sea, soaking you, stopping you in your tracks, impeding your salt-encrusted progress. And here too is the sea, its waves knocking you off balance so you must reconsider what you know of the view: an arresting vista, the promise of atonement in your return.

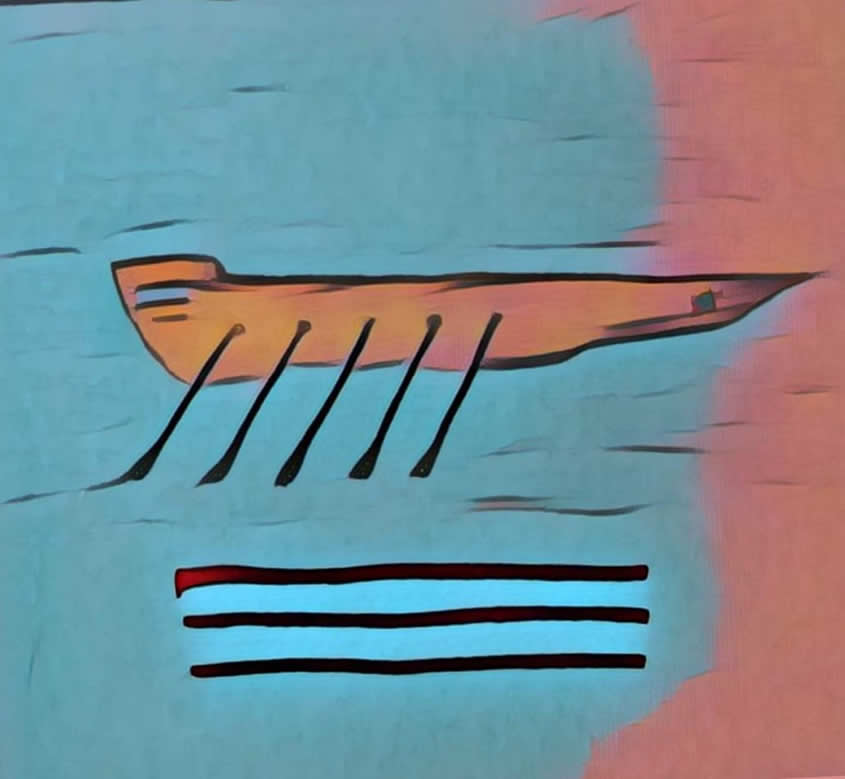

Someone is saying, Put your mouth on mine, put your mouth on mine and let us create a pleura to sustain us. Put your mouth on mine, put your mouth on mine and walk carefully, this way, side to side to the water’s edge, tilting our heads together to see: the empty inner tube, the vacant skiff, the remains of a flying machine. Put your mouth on mine, breathe and don’t worry about the aftertaste.

Es un soplo la vida!

Oh, yes, you have returned and you want to drop to your knees and kiss the ground, embrace the columns in the old city, the neighbor who remembers you when you were a newborn and not yet in exile, not yet marked for departure, by air or water, solo or accompanied, legal or illegal. Behind you, you hear someone saying, You, returnee, what did you bring me? But no, don’t turn your head, stay here, disseminating emotions in our shared spit. Put your mouth on mine, put your mouth on mine. Your step is halting: You’re obeying this ritual⏤a convention with which you’re utterly unfamiliar⏤and have surrendered to this breathing down each other’s throats like a native.

Later, you will confuse the beginning and the end of the journey, the packing and unpacking and repacking of your bags. You will forget what you brought to give away and what you brought to put back in its proper place. El olvido que todo destruye. You will be confused about what to take, what to accept, what to leave behind. You will weep while walking on the boulevards and you will notice that, as you pass, the students on the seawall are also weeping, as are the young mothers and the pickpockets, the new entrepreneurs and the masturbators.

Someone will say, Put your mouth on mine and someone else will say, We are all weeping because you weren’t here, we are wrecked because you weren’t here, how can we have talked about progress without your input, how can we have contemplated the beauty of the sea without your voice in the national discourse? We are weeping because there is a hole in the nation where you should have been, a deep and painful hole, a black hole with your name on it. Now put your mouth on mine and breathe carefully, walk warily, hold on, put your mouth on mine and let’s tilt our heads toward the abyss and be careful not to fall. Put your mouth on mine and don’t worry about the aftertaste, it’s nothing, it’s the taste of nothing, the wind, a goose egg, a knot on the quipu. Put your mouth on mine and let the wind become a voice that tells the story in which the goose egg is you.

Tengo miedo del encuentro. Tengo miedo de las noches que pobladas de recuerdos encadenen mi soñar. Tengo miedo de decirte que te quiero y no quererte. You ever feel like nobody (n)ever understands you but you?

Cultivo. Cultivo una rosa blanca. Cultivo una rosa blanca en julio como en enero. The sea. The blue sea. The blue sea beneath the battleships, the freighters, the cruise ships The blue sea beneath us, beneath the empty inner tube, the vacant skiff, the remains of the flying machine. It’s a short distance. A meager expanse.

Put your mouth on mine.

Put your mouth on mine.

Y qué, eh, y qué?

You have returned to shake hands with everyone, with sworn enemies and innocents, con el amigo sincero, con el cruel que me arranca, with the carefully selected audience that has been prepared for your performance. You shake some hands with reluctance and others eagerly, but you shake and shake until someone hands you a script and then you stop and stare. Oh you recognize this⏤a lullaby, a presidential address perhaps⏤but, goddamn it, how do you read that accent? How do you bring all the eloquence of your heart to the moment when your tongue stumbles and falls like a tourist who’s gone too far out on a tamarind limb?

Cultivo una rosa blanca, carajo.

You set out to write your autobiography, which will be a collective biography of all the people who were exiled with you. You want to be understood, you want to be precise, so you leave out metaphors, you leave out anything that could be symbolically confusing, you leave out the politics, you leave out the part about exile and your mouth on mine. Using a long goose feather quill, you write: I have come back to extend my hand in kinship. You write: Sometimes the most important changes happen in small places. You write: The tides of history can leave people in conflict and exile and poverty. You write: It takes time for those circumstances to change. You write: The recognition of a common humanity, the reconciliation of a people bound by blood and a belief in one another… You tilt your head towards the water’s edge, the black hole.

Put your mouth on mine.

It’s an order, man, do you not understand?

Exile is actuality, animation; exile is endurance and presence, the rat race, the real world; it’s the journey and the entity you sleep with every night, the subject of every memo, every recipe, every instruction manual, every warranty and contract. Exile is everything, everything possible within the possibility of return.

Finally you go to that one boathouse, the one you’ve never seen, the one you were born in. You read all about it in the guidebook on the bus on the way there. How it’s surrounded by palm trees growing out of the water, how it’s guarded by angry geese that bark when you near it. When you get there, the colors are beautiful, long splashes of orange in the sky, a circuit of white orchids ringing their bells. You want so much to feel, to gasp with wonder, to identify. You want the geese to bark, to bite your ankles and maybe draw a little blood. But they are tired, curled like kittens on the water’s edge. You want desperately for someone to approach you and ask you to put your mouth on their mouth and breathe some kind of warmth but it’s lonely here, lonely, and soon very dark. You break into the boathouse, which is dilapidated and slippery with moss. You let yourself fall into the moss, make a bedding from it, smoke some. You entertain yourself making nautical knots you learned abroad: the Alpine Butterfly Loop, The Trucker’s Hitch, The Zeppelin Bend. The wind is blowing through the boathouse and it’s a lovely music. When you wake up the next morning, you need a moment to remember where you are. You decide not to eat your provisions, not to open your thermos. You will, instead, live today like those who never went into exile. When you peel away the moss and lift up the floorboards to get at the water, you realize the boathouse has been unmoored. You lean over the edge and, swatting away the geese, you drink from the sea, you drink and drink the salt water until your belly bloats. En julio como en enero, cultivo. This is a pain you can live with.

Achy Obejas is a writer and translator. Her new book, The Tower of the Antilles, a collection of short stories, will be published next year by Akashic Books. She is currently co-director of the Mills College MFA in translation, which she conceived and founded. For more info about the program, go to http://www.mills.edu/mfa-translation. For more info about Achy, visit achyobejas.com

bellísimo, mil gracias, this arrived in my inbox just as i’m preparing to depart…

La decisión sobre el significado del regreso depende del contenido, es cuando uno se plantea el regreso que sucede el regreso…aquí Achy nos conduce al regreso y la siguiente posibilidad es evidente. Geografía de un espacio que se abre. Mis felicitaciones para A. Obejas y Eduardo Aparicio por tan importante traducción.

Captivating piece, Achy. Masterful.

Una narración muy hermosa y muy emotiva, aunque deben editar el último párrafo porque hay un fragmento que se repite varias veces “Finalmente vas a ese cobertizo para botes …En julio como en enero, cultivo.” Merece ser enmendado.

Es una narración muy hermosa y muy emotiva, aunque el último párrafo debe ser editado porque está repetido varias veces. El fragmento que se repite: “Finalmente vas a ese cobertizo para botes …. En julio como en enero, cultivo.”