Hola Reader-Friends,

As this is our first post in 2016, we want to begin by wishing all of you a very happy new year! We thank you for your support and look forward to hearing from you. This month we are delighted to have Rosa Lowinger blog for us; she is a renowned conservation specialist, curator, and writer. Her piece reads like a detective story and addresses an important motif in Cuban folklore—the idea that buried treasure abounds on the island, a metaphor, perhaps, for memories left behind and futures that never came to pass. Enjoy and please share your own buried treasure stories!

Abrazos,

Ruth y Richard

by Rosa Lowinger

Read post in Spanish >>

In January 1961, shortly before my parents left Cuba for good, my father and grandfather hid $200,000 in a false ceiling they built into the hall closet in my grandfather’s apartment. The bills were bundled with rubber bands and stacked onto a plank that was screwed into a ceiling, then carefully wallpapered over, so no one would find it before my family returned. Six years later, my grandparents also left Cuba. The money was never recovered.

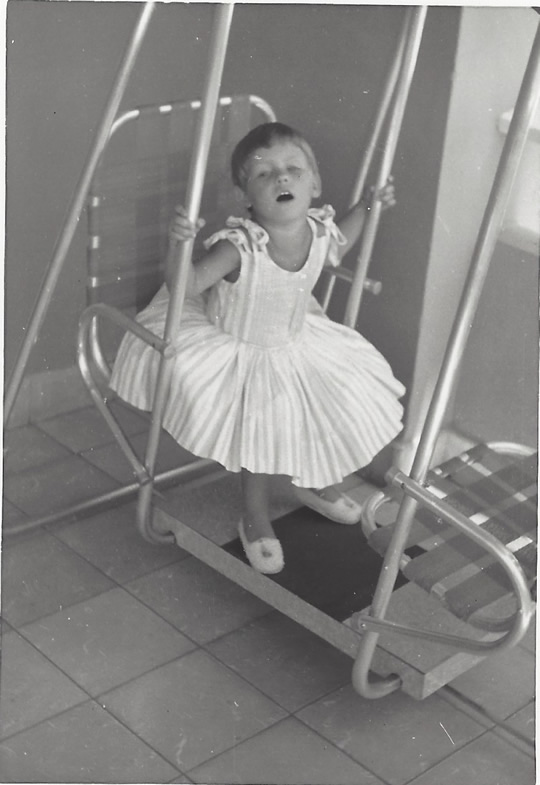

Rosa Lowinger as a child on the balcony of her family’s Vedado apartment. Photographer unknown, collection Rosa Lowinger

I learned about this story for the first time in May 2000. By then, I had been going back to Cuba for about seven years. My trips were always related to my profession, which is conservation of art and architecture. Havana is a city that begs for conservation. Everywhere you look there is something of historic value that needs to be repaired. I had not known this about Havana growing up. My family was either unaware of the wealth of architectural detail that our hometown contained, or uninterested in wealth of that sort. I, on the other hand, made (and make) my living preserving and restoring the sculpture and the decorative surfaces that make historic buildings historic. Things like tile murals, terrazzo pavements, bronze lighting fixtures, mosaics, and painted or cast concrete decorative finishes. The first time I went back to Cuba was to give a paper at a preservation conference. I was then invited to teach workshops at the now defunct Centro Nacional de Conservacion, Restauracion y Museologia. Eventually I started working with Cuban contemporary artists, helping them solve technical problems about fabrication and the longevity of their materials as they began selling to the American market, and guiding groups of arts professionals and preservationists on visits to the island.

It was during this latter phase of my travels that my father revealed the story of the buried treasure. I was getting ready for my trip when he casually said, “Hey, if you ever get to our old apartment building, you should try to find the $200,000 your grandfather and I hid in the hall closet.” I was completely taken by surprise by this confession. I knew that my grandfather was well-to-do in Cuba. He’d come as an immigrant in 1921 and by 1959 had two stores and two apartment buildings, including the one where we had lived. To have that kind of cash on hand was another matter. As my father, who had been through a series of economic troubles in the U.S. explained how they had hid the money, I felt his loss and his pain. I also had no intention of looking for the money.

During the telling, my father talked in detail about how high the ceilings were, how difficult it was to drill into the concrete block, and how the wallpaper, which had a busy pattern of orange trees and abstract swirls, had to be secured by false moldings to appear authentic. I recognized this sort of talk—it’s the kind of information people in my field toss around. So to change the subject a bit from the anguish of loss I asked him, “How do you know so much about the building’s construction?” My father then dropped an even bigger bombshell on me: “How do I know? I designed the building, that’s how.” Talk about a buried bit of treasure. My father, who was not an architect, designed a building. Turns out he wanted to go to architecture school but his father insisted that he work in the family store. As a concession, he bought a plot of land and told my father “if it’s so important to you to design a building, go ahead and do one for us.” So my father drew the structure, taking cues from the architectural magazines that were popular in 1940s Havana. Then my grandfather hired “a real architect” to draw up accurate plans.

The building is a modest structure in Vedado, close to the Malecón. In my profession we call the style “ordinary, everyday modern.” This means that it is not splendidly decked out, like the Hotel Riviera, or formally exquisite like Max Borges’ Tropicana Nightclub, or grand like the Nuevo Vedado houses that boast soaring, cantilevered rooflines. But it has a decidedly modern flair, even from the outside. I’d walked past it many times over the years, but had never thought to go inside. I felt weird about having people think I was there to scope out my family’s property for some future claim, which I decidedly am not. But I happened to tell the story of the hidden treasure to some friends in Havana—an artist named Alex and Aquiles, his studio assistant. A rising art star who was already commanding high prices for his works, Alex took the story in the same spirit as I did: as one of the many buried treasure stories that Cuban exiles like to tell. Like me, he recognized that the detail of my father having been the building’s architect was the more valuable morsel, for it revealed something about my own life choices. Conservation is a weird profession, and I never really understood how I came to urgently love repairing material things. Now it made sense.

Exterior of the Alberto Lowinger apartment building, architect Leonardo Lowinger, 1950. Photo: Kyle Normandin, 2016

For Aquiles, the studio assistant, the architecture story was a charming sidebar to the main tale: there was $200,000 hidden in a ceiling, potentially up for grabs. Being one of those agile street guys who knows everything and everybody in Havana, he asked me the address. I told him and it turns out that an old girlfriend of his named Liana just happened to live in the apartment in question. The next day, he went over and scouted the situation. He came to me with a plan. “Liana’s in Spain, but her grandmother rents out her room,” he reported. “I told her I needed it to spend the night with my new girlfriend—una norteamericana whose grandfather lived in that apartment.”

The next afternoon I went over there with him. Liana’s grandmother could not have been nicer. She served us coffee and chatted away about how much she loved the building, revealing not a shred of surprise that a forty-something woman was having an affair with a 23-year old and that she was prepared to pay $30 to sleep with him in her own grandmother’s bed. To be clear: I was not having an affair with Aquiles and all I wanted to do was have everyone go away so I could feel the space that my father designed without everyone’s eyes on me. My father was a mere 17 years old when he did the work but in its decorative details you can clearly see that he was a gifted man, a true modernist. At seventeen he had convinced his practical immigrant father to install boomerang-shaped wood dividers between the living and dining rooms. The front doors of each unit were frosted glass with metal framing. Most astonishing of all was the central hallway with its curved aluminum banisters, black terrazzo floors and walls faux-finished to resemble travertine. I never understood my father until that moment when I sat in that living room, seeing what he’d designed.

Interior staircase and hall of the Alberto Lowinger apartment building, architect Leonardo Lowinger, 1950. Photo: Kyle Normandin 2016

At a certain point I began to realize that the woman was well aware that my grandfather had not simply lived in the building, he had been its owner. She worked to impress me with stories of how well the present residents cared for it: “We have a maintenance committee that inspects the roof every month and prepares a barricade to protect the underground garage when there’s going to be a storm…” The subtext was clear: This building might have once been your grandfather’s, but it’s ours now. I had no proprietary intention at all, but her tone annoyed me. No, the building is and was and will always be Leonardo Lowinger’s, the same way Tropicana will always be Max Borges’ and the De Schulthess house will always be Richard Neutra’s… I thought. Then she dropped a bombshell similar to the one my father had, just several days earlier: “The building is better built than all the ones around it. That’s because the owner’s son designed it. There’s one just like it in Lawton.”

We spoke about my father for a while. She knew he was the designer because it had been passed down from resident to resident, from the building’s caretaker, el encargado, who, incidentally my family had reviled over the years because he was un comunista who helped nationalize the property back in 1960. But he had made sure that the residents knew that the old man who owned the building had a son who designed it. I told her that he had never designed another building, that he never studied architecture. She said that was a shame, because he clearly had a talent. I told her that I restore historic buildings, and that modern ones are my favorites. “At least the talent continues,” she said, and we all got up to go. As we said our goodbyes, arranging for the following night’s “tryst”, I decided to just ask to see the hall closet. The woman amicably opened the door. The closet was crammed with clothes and tools and other things. To my relief, the wallpaper was gone. There were traces of it, but the closet had clearly been altered. Aquiles was disappointed, but I convinced him that the story was even better than the money itself. We wrote a short story together about it. As of this writing we are developing it into a screenplay. It makes him happy.

Rosa Lowinger outside of her family’s apartment building. Photo-Catherine Meyler 2015

When I returned to Miami, I told my father that I’d been inside the building. I showed him pictures and told him that the residents knew he designed it and were grateful for its quality. I knew it was not enough to bridge the gap of loss, but it meant something to me to offer him this a bit of solace. He was quiet for a while, then he said, “I did another one for your grandfather, in Lawton. You should try to find it some time.”

Rosa Lowinger is president of RLA Conservation, Inc. a materials conservation firm with offices in Miami and Los Angeles. The co-author of Tropicana Nights: the Life and Times of the Legendary Cuban Nightclub, (Harcourt, 2005), she writes frequently about Cuban art, architecture, and Havana’s 1950s nightclub scene. In 2013 she curated Concrete Paradise: Miami Marine Stadium at the Coral Gables Museum and is presently guest curator for the Wolfsonian Museum exhibit Promising Paradise: Cuban Allure, American Seduction that will open in May 2016.

Spanish translation: Eduardo Aparicio is a translator, writer, and photographer. He was born in Guanabacoa, Cuba, and currently lives in Austin, TX, where he’s president of AparicioPublishing.com.

What a great read!

Muy lindo te quedo , Rosi. Un abrazo muy fuerte, RAke

I visited my grandmother’s home in the Santo Suarez neighborhood in Havana where I lived with my father, mother and younger brother before I left Cuba in the year 1960. It was designed and built by my grandfather as well as the house next to it and two “solares” adjacent on each side of the two houses.

I had traveled to Cuba with my youngest son who insisted on visiting my home. I knocked on the door and an elderly lady answered, who I’d never met or heard of, and was living there with her grandson and his two children. I told her that this is where I lived and that I wanted to visit the house and remember.

She was gracious and allow me to visit everywhere in the house. It was very emotional and brought tears to my eyes. Before I left I told her that my house was now hers and that I will never make a claim on it. I gave her a hug and $100.00 and have never been back, even though I now visit Cuba often.

Such a wonderful story, so full of intrigue, and so very well told. I held on to every word until the end, enjoying the suspense, and thoroughly enjoyed the photos. Thanks for publishing.

This is truly “one of the many buried treasure stories that Cuban exiles like to tell”…..

Such a powerful story that goes beyond a materialist treasure. Rosa Lowinger, I enjoyed reading your story because of the meaning “treasure” was later transformed into a personal, cultural connection to you and your profession. Thank you for providing photos and detailed descriptions about your journey. I enjoyed every piece of it. How has your work today impacted you, now that you know your father has built buildings in the past? Has this story influenced you to start new projects?