Since last month’s post we’ve witnessed the election of Donald Trump and the death of Fidel Castro. In contrast to these swaggering male figures, this month Margarita Engle shares with us her passion and motivation for writing about history’s unsung heroes and forgotten poets who’ve struggled for change through non-violence in often hopeless situations. She reminds us of the importance of connecting past and present through the bridge of literature, especially for younger readers to have a more complete picture of Cuban history. As both Cuba and the United States look ahead to an uncertain future, there is no better moment than this to think about how to pass on to the next generation the stories of those who wished for peace.

by Margarita Engle

My status as a Cuban-American is unusual, because I am neither a refugee nor an exile. My father is an American artist who traveled to my Cuban mother’s hometown of Trinidad after seeing photos in the January, 1947 issue of National Geographic. He met my mother on Valentine’s Day, on the terrace of a colonial palace that was being used as an art school, and is now known as El Museo Romántico. When my parents met, it was love at first sight. They could not speak the same language, but they were artists, so they passed pictures back and forth to get to know each other. Within a year, they were married. They moved to my father’s hometown, Los Angeles, where my sister and I were born and raised. During summer trips to the island to visit my mother’s extended family, I fell in love at first sight too. I loved my abuelita, bisabuela, tíos, and primos. Many were educated, but others were guajiros, country people who lived on farms, rode horses, rounded up cattle, chopped sugarcane, and picked wild fruit, the brilliantly hued mamoncillos and mameyes that I still remember as vividly as if they were made of light beams that can travel across years and decades.

Trinidad, Cuba, birthplace of Margarita Engle’s mother

During the school year in Los Angeles, I was a bookworm who loved adventure stories and poetry. In Cuba, the adventures were real. I fell in love with tropical nature, playing with flowers, catching tarantulas, and fulfilling my dream of riding horses. Some of my cousins and uncles were barbudos, bearded revolutionaries who fought with Che Guevara in the Escambray central mountains, and later fought against him once the land reform reached smaller farms.

We were in Cuba during the summer of 1960, when diplomatic relations with the U.S. began to break down. Subsequent years brought the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the October Missile Crisis, the trade embargo, and the travel ban. When I was a teenager in the 1960s, it was easier for a U.S. citizen to walk on the moon than to visit relatives in Cuba. Without those summer visits, I felt as if I’d left an invisible twin behind on the island, the girl I would have been if we’d lived in my mother’s homeland instead of my father’s.

Throughout three decades⏤from 1960 to 1991⏤memory served as a form of magical bridge across time, helping me feel complete. Still fascinated by tropical nature, I studied botany and agronomy, became the first female agronomy professor at a technical university in California, and then, during a graduate seminar in creative writing taught by the great Mexican-American poet Tomás Rivera, rediscovered my childhood love of creative writing.

During the summer of 1991, after the fall of the Soviet Union, non-eastern Bloc travelers were allowed to attend Havana’s Panamerican Games. Since Cubans were not yet allowed to interact with foreigners, I visited relatives secretly, making my life feel even more surreal than before those hidden family reunions. I flew to Trinidad on a plane so small, and so old, that the pilot stuck his head out the window to wave at people on the ground.

On Margarita’s family’s farm

I continued traveling to the island frequently during El Período Especial, the Special Period of the early 1990s, when Cubans were so hungry and desperate that tens of thousands took to the sea on flimsy rafts. My novels about that era were written in prose, for adults. It was not until I decided to write a historical novel about Juan Francisco Manzano, El Poeta-Esclavo de Cuba (The Poet-Slave of Cuba), that I switched to free verse. For the past decade, I have written almost entirely in verse, and almost entirely for children and teenagers. I tend to write about people who are not famous in the U.S., trying to bring forgotten heroes back from the margins of memory. I am especially fascinated by those who found nonviolent ways to struggle for change, clinging to hope in situations that must have seemed hopeless. Rosa la Bayamesa, in The Surrender Tree/El árbol de la rendición, was a wilderness nurse who healed soldiers from both sides during Cuba’s wars for independence from Spain. Fredrika Bremer, a Swedish suffragist in The Firefly Letters, and Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda, the great Cuban poet in The Lightning Dreamer, used the written word as a weapon against slavery and the oppression of women. Antonio Chuffat, in my newest historical verse novel, Lion Island, documented freedom petitions written by the island’s indentured Chinese laborers. In an effort to bring the past back to life, I write these biographical stories in present tense, hoping to offer young readers a sense of immediacy that could be described as time travel. By writing in free verse rather than prose, I try to offer a welcoming page, filled with rhythmic language that can serve as a musical bridge between thoughts and feelings.

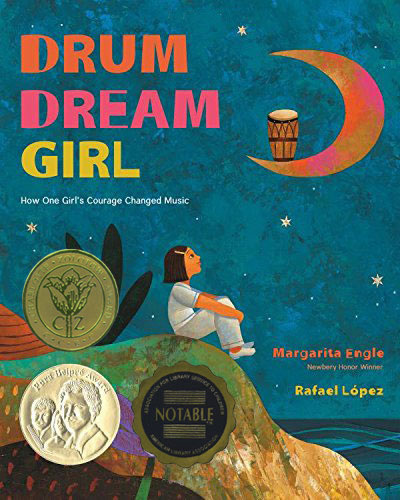

Margarita’s most recent picture book

Each time I return to the island, I see small, hopeful changes, such as farmers’ markets and a flourishing of the arts. A few years ago, I decided to write a verse memoir, Enchanted Air, Two Cultures, Two Wings. With no visible sign of a Cold War thaw on the horizon, I had given up dreaming of a renewal of diplomatic relations within my lifetime, so I wrote my childhood memoir for young readers, assuming that a future generation would be the one to finally make peace. I have never been so thrilled to be wrong. Advance review copies of the memoir arrived on my doorstep during the same week when President Obama announced plans for a gradual reconciliation. I felt as if I had written a prayer, and miraculously, it had been answered, transforming my plea into a song of thanks. I hope that children who feel marginalized, divided, or doubled by history⏤or any other strange aspect of reality⏤might find encouragement in the story of a girl who wished for peace.

I began writing about history’s nonviolent heroes because I admire them, and because so many North Americans know so little about Cuba. When I visit schools in California, children don’t ask, “Where is Cuba?” They ask, “What is Cuba?” Even many of their teachers learned nothing about the island in school. Just last month, I met a high school U.S. history teacher who thought Cuba was a protectorate of the United States, like Puerto Rico. However, President Obama’s efforts have inspired me to move into the present. My next middle grade verse novel, Forest World, is an adventure story set in modern Cuba with a strong environmental theme (forthcoming, Atheneum, fall 2017).

Now, quite suddenly, right after a bizarre U.S. election, the future is once again baffling. What will Trump do? I find it impossible to understand my own complicated emotions as I wonder about the future of U.S.-Cuba relations. I am fearful, sad, and angry. I feel like a storm. President Obama’s legacy of peacemaking deserves to survive, but as an individual with family on both sides of a threatened bridge, I feel just as helpless as I did when I was a child. All I can do is wait, and hope.

NO PLACE ON THE MAP

(excerpt page 11, Enchanted Air)

After those first soaring summers,

each time we fly back to our everyday

lives in California, one of my two selves

is left behind: the girl I would be

if we lives on Mami’s island

instead of Dad’s continent.

On maps, Cuba is crocodile-shaped,

but when I look at a flat paper outline,

I cannot see the beautiful farm

on that crocodile’s belly.

I can’t find the palm trees,

or bright coral beaches

where flying fish leap,

gleaming

like rainbows.

Sometimes, I feel

like a rolling wave of the sea,

a wave that can only belong

in between

the two solid shores.

Sometimes, I feel

like a bridge,

or a storm.

Margarita Engle is the Cuban-American author of verse novels such as The Surrender Tree, a Newbery Honor winner, and The Lightning Dreamer, a PEN USA Award winner. Her verse memoir, Enchanted Air, received the Pura Belpré Award, Golden Kite Award, Walter Dean Myers Honor, and Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award, among others. Margarita’s books have received multiple Pura Belpré, Américas, International Latino, and Jane Addams Awards and Honors, the Claudia Lewis Poetry Award, and an International Reading Association Award. Her most recent picture book, Drum Dream Girl, received the Charlotte Zolotow Award for text.

Margarita’s newest historical verse novel is Lion Island, Cuba’s Warrior of Words. She lives in central California, where she enjoys helping her husband train his wilderness search and rescue dog.

Wonderful piece by Margarita Engle. It brings back so many memories for me, who admire the author for her adventures in narrative verse

“All I can do is wait, and hope.”

I do more than “wait and hope”.

I returned from Cuba about two weeks ago after installing two water purification systems in Cuban churches. One in San Cristobal and the other just east of Baracoa in the hurricane damaged area.

I will be speaking at the University of Miami in February where I will ask for a leader of each Christian denomination, a Jewish Church leader and the leader of the Catholic Church in Miami, Florida to appeal to the Cuban-American community to end the Embargo.