This month we are proud to showcase the incredible prose and poetry of Carlos Pintado. In this piece, he uniquely and beautifully explores various dimensions of “home,” asking us and himself some very important questions: Can we ever go back home? Is home nothing more than myth—a fiction? Is memory the only bridge back home? Questions that Carlos deeply ponders while reflecting on the past of his Cuban childhood and his relationship with Cuba today. Questions that affect many Cuban-Americans, but also universal questions that we all ask ourselves throughout our lives. And with a stunning evocation of Dulce María Loynaz’s poem about her loss of home, he connects past and present with grace and hope.

Abrazos, Richard and Ruth

By Carlos Pintado

“I’m a stranger in a strange land”

Carson McCullers

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter

The second time I went back to Cuba, in 2012, invited by a filmmaker friend to serve on the jury at the Gibara Film Festival, I suddenly recalled the Japanese legend of Urashima Taro, which tells of a fisherman who rescues a giant turtle (in reality, the daughter of the sea god) from being tortured by a group of children. The fisherman is rewarded by being taken to the Dragon God’s palace at the bottom of the sea, where he lingers, enjoying the delicious food and even falling in love with the sea god’s daughter, until after two days have passed he asks to be returned to his home village because he misses his ailing mother. Once back on the beach, the fisherman notices that something strange has happened: the houses are all changed, the paths have shifted, even the sea waves break differently. Like a man possessed, he asks desperately for the family of Urashima or Urashima Taro until at last someone tells him that a man by that name lived there a hundred years earlier, and that, according to local legend, he had entered the sea and never returned.

What always fascinated me about this fable—much more than its elements of fantasy, enchanting as they are—was the way it depicts a man suddenly forced to face a new reality. What has more weight for someone at that moment: the nostalgia for a past that will never come back, or the inevitable wonder at a surprising, perhaps promising present? Adapting to change or losing your mind, that’s the “To be or not to be” of our mental health.

On that occasion I thought about myself and Urashima Taro, setting aside the obvious differences between us: do we change ourselves, or do the cities where we live change us? Did the Japanese fisherman perhaps change more in three days than his village did in a century?

As always after a long separation, my sister and I stayed up talking till the early hours of the morning. In my memory I retained the image of our house in Pinar del Río, on the outskirts of a small town called Las Martinas that few people have ever heard of, because it is located at the literal end of the earth. Our conversation took place, however, in a brightly lit Havana, far distant from that other Havana of constant power failures and blackouts, floundering in the doomed years of the poorly named “Special Period” that so tormented us back then.

“The house isn’t there anymore,” my sister said, in the kind of voice you hear in dreams.

“Isn’t there? What happened?” I asked.

After I left Cuba on January 28, 1997, putting my faith in Martí and the saints, ownership of the house passed to a cousin, who naturally wasted no time in fixing it up and remodeling it until in the end he had built a new house on the spot where mine once stood. I can’t blame him. I would have done the same.

As in the Japanese fable, the house was no longer my house, the village no longer my village.

Before yielding to the waters of sleep, I thought about the strange fate by which the things of this world inevitably seem to abandon us, even when we try to save them through memory: the house where I learned to walk, where I first discovered the wonder of books, where I wrote Habitación a oscuras (In a Darkened Room), my first book of poems, no longer belonged to the kingdom of this world. That miniature version of the universe as we know it in our childhood no longer exists.

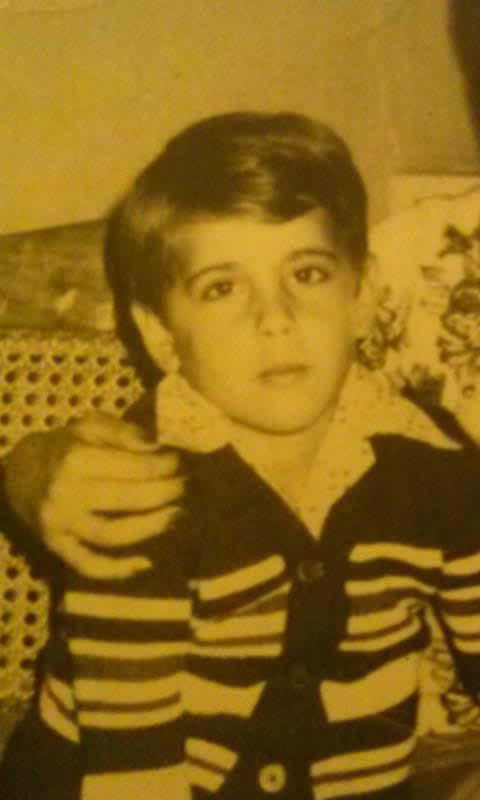

Carlos as a child in Cuba, 1980

That very night I read a poem from the book. It was unquestionably a small, silent tribute to the house of my dreams:

The House

The house, so silent, saves

within itself the chairs, the objects,

spinning wheels, mirrors, books, lockets,

and all the old accumulated dust

that no one will ever want to touch.

The house, so dark in its mystery,

floods the halls for us with voices.

All the silence of the night returns

along the half-seen wall in shadow,

searching for which lonesome phantoms,

calling out to whom, by which unlikely names.

The following day, wandering through an old bookstore, I found myself leafing through a copy of Últimos días de una casa (Last Days of a House) by Dulce María Loynaz, which I hadn’t read since my teenage years.

Perhaps the sea too no longer exists

Or has been changed, its place

Or its substance. And everything—the sea, the air,

the gardens, the birds—

has also been turned to gray stone,

to nameless cement.

And I realized, at least, that I wasn’t the only one who had lost the house of my past life. And I felt relieved.

The house that inspired Dulce Maria Loynaz’s poem, photo by Ruth Behar

I’m not nostalgic by nature; quite the contrary: I’m the sort who thinks of the future as divine fire, well worth stealing, come what may, who thinks that happiness is built up bit by bit, and that, as in love and war, all is fair too in happiness; and yet something flickers out inside of us when the things that have always stayed with us throughout our lives cease to be. I suppose it’s the desire for eternity or permanence that makes us resist change.

Later that day, to counteract this feeling, I asked about my friends; but like the house, my friends were not there, either. After the stampede of the 1990s, most of them also emigrated to other countries. As if arranging a recalcitrant kaleidoscope inside my mind, I pictured them in Madrid, in Venice among the gondoliers, or acting in and directing some telenovela or other in Mexico.

The heart, as no one knew better than Carson McCullers, is a lonely hunter. And I felt myself a stranger in a strange land. I spent my days on the island making new friends and reading dozens of screenplays that would later be turned, award-winning or not, into feature films. I tried to adapt to this new island, which was no longer my island. My advantage over Urashima Taro—perhaps my only advantage over him—was that I had learned very quickly that the things of this world come bestowed with a fleeting quality, that nothing is destined to last forever. “I am modifying the desert,” Borges said in a poem in which the protagonist (Borges himself, perhaps?), standing some three hundred meters from the Pyramids in Egypt, picks up a fistful of sand and lets it fall, in silence.

The days in Gibara were filled with that special light, so pure it makes everything eternal. My new friends spoke of literature, of film, and of love, placing their bets on a dream-filled future. Most of them exchanged text messages, talked about cell phones and the internet, connecting legally or illegally over phantom servers. For good or ill, they had a vision of the world that went far beyond the Cuba surrounded on all sides by water that was my Cuba. Something has changed, I told myself, and I was glad of it.

A statue on the porch of the Centro Cultural Dulce Maria Loynaz, photo by Ruth Behar

I saw that even under the most trying circumstances people never stop dreaming, and that this is our lifesaver when the ship founders.

At some point I started writing the story of this story: it was to be a very Caribbean—better yet, a very Cuban—version of the fisherman Urashima Taro. I’d have to imagine what must have gone through his head when, after three days at the bottom of the sea, he returned to the same place he had left and realized that a hundred years had actually gone by, and that everything he remembered about his life and his village had already fallen into oblivion. I wouldn’t write a disquisition about worlds in transformation but about the soul that is always hovering over a candle flame. That’s how we live. Someone or something blows on us from nearby. The world changes scenery.

Accepting this is a difficult but necessary birth. You don’t have to be a theosophist to notice. My story would begin by jabbing my finger into my own wound, traveling around a city that is familiar and strange at the same time. It doesn’t much matter whether three days or a hundred years have passed.

Translated from the Spanish by David Frye, a translator and anthropologist who teaches at the University of Michigan. He has translated more than twenty books from Spanish to English, including the novels Simone by Eduardo Lalo (University of Chicago Press) and Planet for Rent by Yoss (Restless Books).

Carlos Pintado is a Cuban–American writer, playwright and award-winning poet. His book Habitación a oscuras received the prestigious Sant Jordi’s International Prize for Poetry. In 2014, Carlos Pintado was awarded the Paz Prize for Poetry (The National Poetry Series), judged by U.S. Presidential Inaugural Poet Richard Blanco, for his book Nine coins/Nueve Monedas (Akashic Press), which was included in World Literature Today’s annual year-end list of notable translations. His poem “The moon” was selected as the featured poem of the September 6, 2015 edition of The New York Times Magazine by former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey and was also listed among the 10 Best Poems of 2015 by Vancouver Poetry House.

This essay reminds me of my trip to Cuba in 1998, thirty seven years after I left the island. I wandered the streets of Cienfuegos, my hometown, trying to capture my Cuban childhood.

Preciosa prosa y poesia del poeta Carlos Pintado, Felicidades! Me causo mucha nostalgia! También felicitó al profesor y antropólogo, David Frye, por su excelente traducción!

Alma pura