Born in Havana into a Sephardic Jewish family and raised in the small town of Lakeland, Florida, Elisa Albo’s story is quite unique. In this month’s piece, she looks at the many layers and questions that shape individual identity. Tracing three generations, she explores how immigrant journeys, language, and the mix of birthright, culture, and religion define us at any given moment. As we enter a new year full of hopeful possibilities, Elisa’s story reminds us of the relativity of our identity that can change over time, shaped by the forces of history, while still holding on to ancestral legacies from generation to generation.

by Elisa Albo

Read post in Spanish >>

When students at the diverse campus of Broward College in South Florida, where I’ve been teaching for twenty-five years, ask me where I’m from, I’m momentarily stumped. It’s a long and complex story, one I unravel in a poem called “Cuba: A Geobiography,” a word I made up to describe where I come from, what my culture is, who I am. The poem begins, “I was born on an island I have never known,” meaning I was born in Havana in 1960, but we left Cuba when I was only 18 months old. Does my birthplace alone point to who I am? I was also born a Sephardic Jew whose ancestry dates back to Turkey and even further back to Spain before the Inquisition. Is being Jewish what defines me? What about my daughters who were born in Miami Beach? These identity questions of place and journey are at the heart of my geobiography.

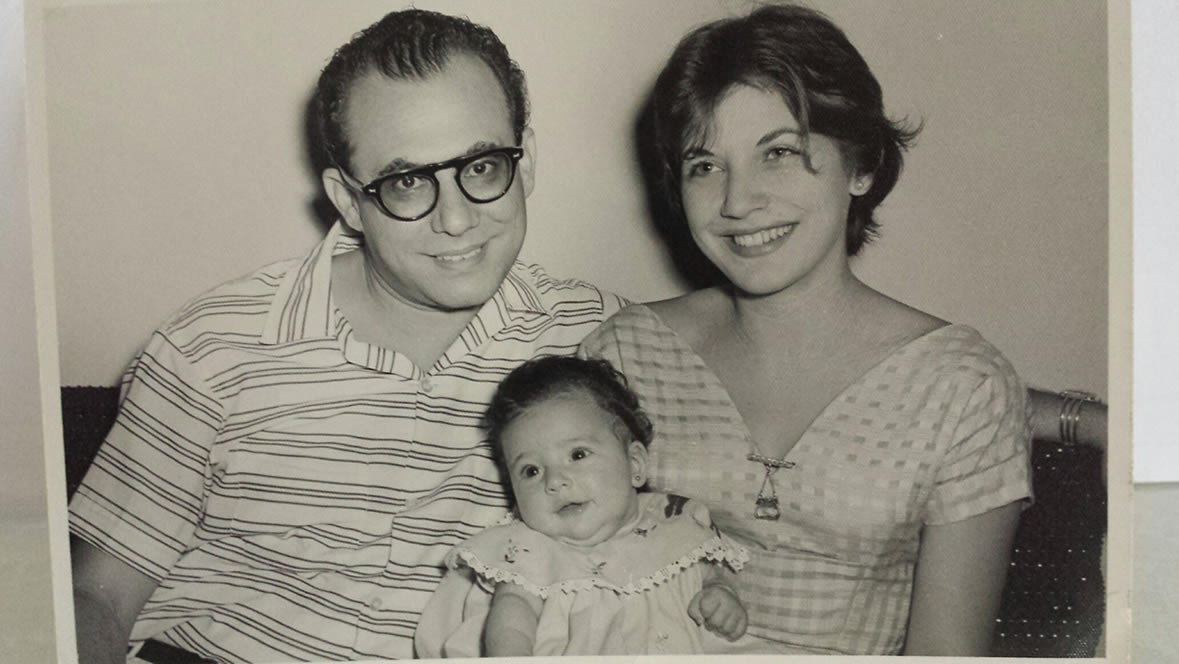

Elisa Albo with her parents at four months old in Cuba.

After leaving Cuba we spent a year in Tampa, survived one winter in Pennsylvania, then lived three years in Gainesville before finally settling in Lakeland, a very Southern town, midway between Tampa and Orlando, with a church at every turn. We rented a little house on the north side of town near Lakeland General Hospital where my father began working as a surgeon. He’d arrived in the U.S. without a penny, but prospered thanks to his education and experience as a physician, which is why, for my father, education was everything.

My education began as soon as we arrived in Lakeland and I started first grade. My grandfather came up from Miami Beach to visit, and we were playing with a ball when it rolled into the neighbor’s backyard. The next day, a barbed wire fence appeared. Within three weeks of having moved in, we moved out. That was our welcome to small town America.

Elisa Albo, six years old, in Lakeland, Florida—sitting with her father at a table set for Passover.

My education continued at Cleveland Court Elementary School when a boy on the playground at recess came up and asked to see the horns in my head. He’d learned I was Jewish and that Jews had killed Jesus. Another time, a man giving away copies of The New Testament could not get me to take the book from his hand. I kept repeating, I’m Jewish. We believe in the Old Testament. I’d learned my lesson. I can see his outstretched hand, the book I dared not touch as if it were electrified.

Then my father sent my younger siblings and me to Santa Fe Catholic High School instead of to Lakeland High School, the public school. He believed we would get a better education at the small private school even if it was Catholic, and we were not. He said to us, You know who you are. What he meant was that we were Jewish.

We got an education all right. There was one Black senior when I started ninth grade and some Americanized, assimilated Hispanics like me, but we never spoke a word of Spanish to each other, and they were all Catholic. There was one other Jewish family with kids. The girl was in my class. We’d been to years of Sunday school and Hebrew school at Temple Emanuel where we learned to read and speak Hebrew and observed the Jewish holidays. At this beautiful synagogue on the lake, near a church, a Methodist college and the Lakeland Yacht Club, we learned much about who we were, yet even there we were the only Sephardic family. The entire congregation was Ashkenazi, of eastern European background. We were a minority within a minority.

My parents had an active social life in Lakeland. Their friends were largely Cuban, and they celebrated together in style, gave frequent dinner parties, hired bands, bartenders, and caterers, but when it came to lunch or events at the private Yacht Club, a quarter-mile from the synagogue in our cultural desert of a town, they couldn’t go as members. They had to be sponsored by friends. Until the 1980s, the club was “restricted”: Jews and Blacks were not welcome as members. When they finally were welcome, at first my parents refused, on principle, but with so few social venues in Lakeland, eventually they joined.

When I was sixteen, my sister and I pulled into the driveway from school as my mother came out of the house with an envelope in her hand. “You’re an American citizen,” she said. I’d never known I wasn’t. I was rarely reminded I was Cuban—despite the food, the Spanish spoken in the house, my parents’ friends, and the music they played at parties. I just was. My siblings and I, unlike our many cousins in Miami, spoke English with no accents.

What we were much more often reminded of was that we were Jewish. Even close friends saw us as somewhat strange, unique, apart. We didn’t go to church every Sunday; while not fully kosher, we didn’t eat pork; and we observed what they viewed as odd rituals and traditions—a new year in the fall, fasting and atoning, a bar or bat mitzvah or bris (a ritual circumcision, which my father performed for many years as the mohel of Lakeland). The biggest issue, I sensed, concerned our utter lack of acknowledgement, much less acceptance, of Jesus and Mary. My father had taught us that Jesus was a great prophet; we were all God’s children, and that was it. My mother says that to this day, close Cuban friends who are Catholic will single her out in conversation: “You people believe….” or “Your people don’t believe….” Even in South Florida in the early nineties, I recall being at a party with many Cuban artists, some of them recent refugees, when a conversation in Spanish turned to “those Jews” replete with negative stereotypes. They had no idea they were in “mixed” company. Among that group, I felt very American—and very Jewish.

In my last year of Sunday school in tenth grade, our teacher told the class that we feel our identity more strongly at certain points in our lives: When we’re young and are told who we are and what to feel, when we’re threatened, when we marry, when we have children, when we suffer, and when we are near death. In between, we struggle. He was talking about religious identity, but being Jewish is not based only on religion. Many Jewish people are secular. It’s our culture, our ancestral inheritance. It’s who we are, no matter if or how we embrace it. When I think about my parents’ immigrant wanderings, that sense of inheritance is especially clear.

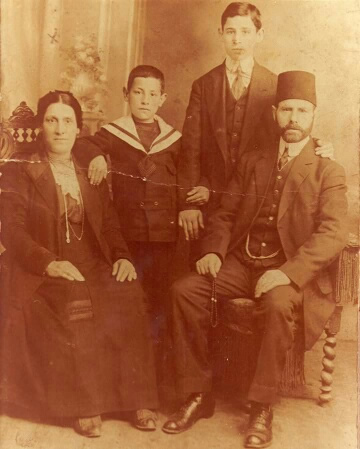

My father was born in Cuba, in Ciego de Avila. As a boy, he moved with his family of six siblings to Havana and went to medical school at the University of Havana. His parents, my grandparents, were born in Turkey, Sephardic Jews who immigrated to Cuba a hundred years ago after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Why Cuba? Mostly to escape conscription into the Turkish army. The young men rarely returned home alive, so the Jewish parents married their children and sent them out of the country. Most never saw one another again.

Elisa Albo’s grandfather Victor Albo (the taller of the boys) and her great grandparents in Turkey.

Also, they spoke Spanish, or rather, Ladino, a language any Spanish speaker can understand. The Jews—a small, insular, religious group—had lived in Turkey for 400 years, precisely from the time of the Spanish Inquisition. In fact, Columbus had to change his port of departure to the New World because the Jews had been given an ultimatum: convert to Catholicism, leave, or be killed. My Spanish ancestors traveled east in Europe, settling in Turkey; others continued on to Italy and South America. Throughout these journeys, they held on to their Spanish. And so I wonder: Is it language that creates us, that defines who we are?

My mother was born in 1942 in northern Spain, in Bilbao, the last of ten siblings. A year later, her father caught pneumonia and died. Her parents were also Sephardic Jews from Turkey who left for Cuba in the mid-1920s to keep my grandfather David from having to go into the army during what is now known as the Armenian genocide. In the decade before my mother’s birth, my grandparents fled the Cuban political turmoil of the Machado dictatorship to Spain, and within a few years endured a civil war, Franco’s fascism, and World War II. My mother’s oldest brothers emigrated back to Cuba. She stayed, and during the 1940s, as she grew up in Spain and before joining her brothers in Cuba, the family pretended not to be Jews, and a nearby convent of nuns helped out my widowed grandmother. My mother was fifteen when she met my father, Jacobo Albo Maya.

In the poem “My Parents Meet,” I write how my parents’ aunts introduce them on a beach, how they marry a year later and have me and my sister before “a revolution…will spin them out over the sea.” Fifty-five years after leaving Cuba, not “a year or two” later, Cuba is still “an island / I have never known.” So am I Cuban? Perhaps—but not only Cuban.

When I met my husband at a poetry reading at a used bookstore/café in Hollywood, Florida, our connection was instant. Five minutes after we met, I said, “If we marry, we’re raising our kids Jewish.” “Okay,” he said, to which I replied, “Now we can continue.” He’s not Jewish; raised Catholic, by age eleven, he had lapsed. For Jews, if the mother is Jewish, the children are Jewish. Our fourteen-year-old celebrated her bat mitzvah last year. Our younger daughter will do the same next year. When I asked her sister how she identifies, she said, “I tell people I’m Cuban.” Do you feel Jewish? “I’m a Jewban,” she says, part of each.

Elisa Albo and her brother in their aunt’s “Florida room” in Miami Beach.

I plan to travel to Cuba in the near future, but what will I find? As I say in a poem, “Can I return to a place that / lives in the liquid center of my imagination?” I am a mix, un arroz con mango perhaps to some, but I see my history as one of an immigrant traveler across time and space, that is, across centuries and continents. My family has done what it had to do to survive and thrive. Now it is my turn to make sure my children do the same and take pride in the journey that defines them. If they ask me who they are, I will tell them:

We wore a Star of David

for centuries before

a guayabera shirt.

We know how to leave,

to pursue shifting winds,

the map of a name:

Maria Dolores Franco de Albo,

my mother who gave

her children no middle

names, saying basta,

enough is enough,

We stay put in the state

with the Spanish name.

La Florida, for now.

Elisa Albo was born in Havana and raised in Lakeland in central Florida. Her poetry chapbook Passage to America recounts her family immigrant story and was recently reissued by Main Street Rag. It’s also available as an ebook. Her chapbook Each Day More is a collection of elegies for friends, family, and strangers. Elisa’s poems have appeared in journals and anthologies, such as Alimentum, BOMB, Crab Orchard Review, Gulf Stream Magazine, InterLitQ, Irrepressible Appetites, MiPoesias, The Notre Dame Review, Poetry East, The Potomac: A Journal of Poetry & Politics, and Tigertail: A South Florida Annual. She has work forthcoming in Two-Countries Anthology (Red Hen Press 2017). She has a Master in TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages) and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing, both from Florida International University. At Broward College for nearly 25 years, she teaches composition, literature, Honors courses, and ESL and has received an Endowed Teaching Award and Teacher of the Year. She lives with her husband and daughters in Plantation (Ft. Lauderdale), Florida.

A beautiful story of origins, belonging, and nature of self. It moves the heart from the first sentence to the last.

A lovely, unsentimental and interesting biography–Elisa fills us with sentiment through her clarity and innocence.

Elise~ your writing is mesmerizing & eloquent…

Wishing you & yours a magnificent 2017!!

Thank you to Ruth & Richard for this sharing this one

♡♡♡

I grew up next to you for many years and I am sorry I never knew you suffered prejudice. I remember attending a dinner with you at the Temple and envying the feeling of community and acceptance I felt there. I really enjoy your writing.

Absolutely elegantly and richly told. i love it.

Thanks for sharing your touching story!

Beautiful!