Dear Friends,

For this post, we wanted to share a conversation we had about the reopening of the U.S. Embassy in Cuba. At the ceremony, Richard read a poem that he’d written for the occasion, “Matters of the Sea,” which Ruth translated into Spanish as “Cosas del mar.” We talked about what the experience meant to Richard and about the inspiration for his poem. We hope you enjoy this conversation!

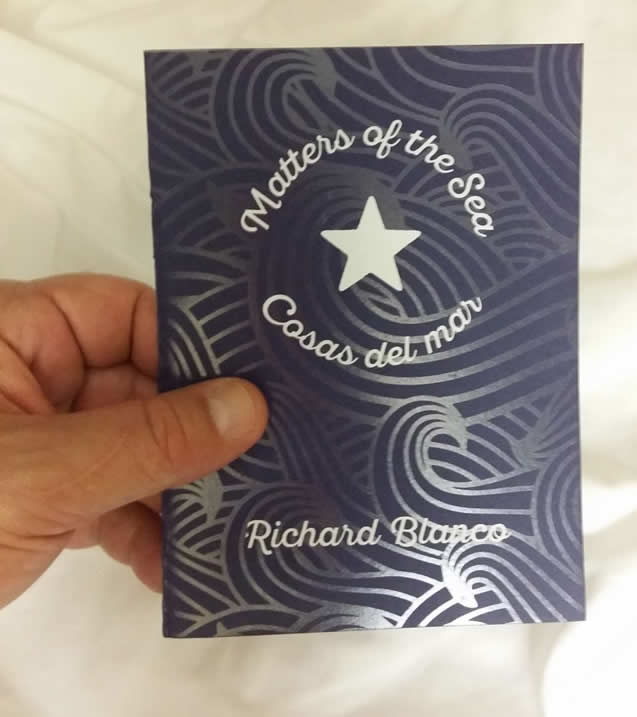

A commemorative chapbook of the poem has just been published in a completely bilingual edition with commentary by Richard and Ruth: https://www.upress.pitt.edu/BookDetails.aspx?bookId=36606

Royalties from the book will be donated to Friends of Caritas Cubana, a non-profit that aids in providing humanitarian, emergency, and social services to the people of Cuba.

Abrazos,

Ruth and Richard

Read post in Spanish >>

Ruth: You write in depth in your book, For All of Us, One Today, about the experience of being chosen to write and present a poem for President Obama’s second inauguration. You felt then that you had finally become an “americano,” and even whispered that thought to your mother before going up to the podium to read your poem. Now this summer, you were chosen to write and present a poem for the reopening of the U.S. Embassy in Havana. Did you suddenly feel you had become more or less “cubano”? If the answer is yes, what kind of “cubano” are you after the event? Have you perhaps become a different sort of “americano” after the experience of writing and sharing your poem, “Matters of the Sea?”

Richard: Certainly, as presidential inaugural poet I began to feel emotionally attached to the United States in a way I hadn’t before; it seemed that the question of “home” had been answered. And, to be honest, the pursuit of my Cuban heritage and urgency to reclaim it had begun to wane. Not only because of my newfound Americanness, but also because the hope of a “normal” and personal relationship with Cuba seemed to be an impossibility in my lifetime. In a way, that hope had significantly faded, just as it had for my mother and many other exiles, as well as many Cuban-Americans of my generation.

But the question of “home,” and all that big word encompasses: country, place, belonging, cultural identity—has no final resolution. Case in point: when President Obama announced his initiative to normalize U.S.-Cuba relations, new as well as old questions about my cubanidad and my cultural home arose. And after my role at the re-opening of the US embassy, those questions became even more intense—and are lingering, still. Questions not about my American identity, but about my Cuban identity. What does it really mean to be Cuban? Was I Cuban enough for Cuba? Do I even have the right to (re)claim my heritage?

Much to my surprise, today I feel less Cuban and more Cuban than ever before. Less so because I’ve realized that being Cuban has to mean more than just drinking café cubano, listening to Celia Cruz, eating guava pastelitos in Miami, and visiting the island every five or six years. Cuba is a real country with real people, real art, and real history that I must get to know more intimately if I am ever going to call myself Cuban. I’m not as Cuban as I thought I was. And yet, ironically I feel more Cuban than ever before because my hope and desire of truly connecting with Cuba in that way has been reanimated, and stronger than ever before. I can almost “taste” it.

Most of my life I’ve been questioning what it means to be an American from a Cuban point of view as the cultural “other.” Now that I feel more grounded than ever in my American identity, I am instead questioning what it means to be Cuban from an American point of view as the cultural “other.” The cultural table has been turned on me! I am delighted by that surprising turn, and welcome the challenge it presents to me emotionally and to my poetry. As they say: good art answers questions, but great art asks them. I am eager to explore new questions about home and belonging in parallel with the new political, cultural, and emotional relationship unfolding between Cuba and the United States. Someday I would like to be fully cubano and fully American, not half of both, but a whole—a fully integrated Americuban, without a hyphen.

Ruth: Looking out at the Malecón and the sea, what thoughts ran through your head just before you stood up on August 14, 2015 and read “Matters of the Sea” on the grounds of the newly reopened U.S. Embassy?

Richard: So many thoughts occurred, as you can imagine. But I would say the most powerful one was not a thought at all, but an emotion—the pure, absolute, sacred feeling of hope. Hope that that moment would spark real transformative changes in Cuba; hope that those changes will bring an end to much suffering and mend the divide; hope—as the poem hopes—that we may all be able to heal, someday; hope for all our tomorrows of silent reconciliation; hope for a happy ending on the horizon.

Ruth: Your Cuban-born mother accompanied you to your reading of “One Today” in Washington, D.C. To your reading of “Matters of the Sea,” on the occasion of the reopening of the U.S. Embassy in Havana, it was your American-born life partner, Mark, who accompanied you, and it also happened to be his very first visit to Cuba. Why was it important that Mark share this experience with you?

Richard: I think there’s another kind of irony here. I feel that my mother’s story as an exile/immigrant is in many ways a quintessential American Dream story. Her faith in that dream—the difficult life-choices she made, all her hard work and sacrifices—is what symbolically and emotionally made that moment at the podium in D.C. possible for me. As such, it was important to me that she be at the inauguration by my side, my American side. At the U.S. Embassy ceremony, however, it was important that Mark be by my side, my Cuban side, for different reasons. Of course Mark had experienced a whole lot of Cuban culture though my family and the years we lived in Miami (including many a Thanksgiving Day with roasted pork!). But I wanted him to see the “real” Cuba—experience the source, see what I had been talking about and writing about for years. Also, thinking ahead to the idea that someday I might legally and morally be able to live in Cuba for a time with him, I wanted him to adore Cuba and its people—luckily he did! Symbolically, however, Mark represented my American consciousness; if he could embrace Cuba, then I too—as an American—could embrace it, and love two countries.

Ruth: “Matters of the Sea” seeks to build a sense of unity between Cubans, all of whom feel a deep connection to the sea. The sea has long been a space of dreams and diaspora for Cubans. But the sea has also been a space of tragedy and loss, going back to the days of slavery and continuing today with rafters who sacrifice their lives to get across to “the other side.” Did you find it difficult to “navigate” all of these complexities? Is there a tone you were going for in your poem that could express both the wonder and the sorrow Cubans associate with the sea?

Richard: To be clear, the occasion demanded that the poem address not only Cubans, but also Americans—the United States. So, really, my audience was three-fold: America, Cubans in America, and Cubans on the island. But of course, the emotional core of the poem is the relationship between Cuban-Americans and Cubans. That was indeed the most emotional and difficult complexity I had to navigate, both collectively and personally. On the one hand, I’ve lived with and written about the painful stories of my exile community, my family in Cuba, the Mariel boatlift, the Cuban HIV/AIDS camps, the Mariel boatlift, and the rafter crisis of the 1990’s. In other words, much of the pain and suffering, the tragic loss of life, the endless plight of our people everywhere. But, on the other hand, I’ve also lived with our heroic hope of someday being one people again, the unyielding strength of our family ties (despite politics), and our unspoken desire to find a way out of the pain, anger, and resentment. The sea, which can be melancholy and sad, as well as transcendent and uplifting, felt like the right imagery to evoke that bitter-sweet tone which seems to haunt our lives and our history to date. In the end, however, I wanted the sea—the poem—to echo not just what was or what is, but more so to offer us what could be. The poem is ultimately about the hope of someday healing.

Ruth: When I told you that José Martí studied and wrote about the work of Walt Whitman, you were pleasantly surprised. Did the Embassy experience bring the poetic traditions of Martí and Whitman together for you in a new and unexpected way? You’ve also noted that the poems of Elizabeth Bishop have been a strong influence in your work. What has drawn you so strongly to her writing?

Richard: Yes, I realized that in similar ways Whitman and Martí were both trying to grasp the essential character of their respective “peoples” and define “homeland.” Reading Martí’s essay on Whitman felt as if I was listening to my Cuban “half” in conversation with my American “half.” As such, I also realized that the quest for cultural and national identity is more universal than I had thought. I think this is why I also connect to the work of Elizabeth Bishop so intensely. One would think that the life and work of a New England woman like Bishop who attended Vassar would have nothing to do with the life of a child of Cuban exiles like me raised in Miami. But the power and beauty of poetry connects us to the core emotions we all share as human beings, e.g. love, anger, loss, triumph. And in the case of Bishop’s work, it’s that universal longing to belong to something, someplace, and/or someone which connects me to her across cultural differences. She was effectively orphaned when she was four years old, and so I recognize in her work questions similar to my own about home and belonging, and a parallel to the emotional complexities and psychology of exile. And also, she was gay, like me; I think that adds another layer to our shared search for home—not in the physical sense, but in the sense of home as a safe space where we can be who we truly are without fear or shame. And there’s yet another dimension to my attraction to Bishop. Seeing myself in Bishop—in the “other”—has instilled in me the sense that emotions are universal, despite any specific cultural settings. As such, I wrote with more confidence, believing that my story and that of my exile community was in the end about the universal search and struggle for home. Bishop, Martí or Whitman—we are all “other” and yet we are all the same.

Ruth: If tomorrow President Obama named you a poet-ambassador to Cuba, what would you want to accomplish?

Richard: What a great title—poet-ambassador! It would be my dream job—that’s for sure. One of the main roles of an embassy is to promote professional, educational and cultural exchanges—and that’s what I would do, with a particular focus on exchange between Cuban islanders and Cuban-Americans, especially those of my generation. I think that relationship is key because it’s at the emotional and political core of everything that is at stake; its successful development could serve a kind of compass with which to navigate the waters of change and sustain a mutually beneficial, symbiotic, and respectful relationship among all Cubans, and between the U.S. and Cuba. On the professional front, Cuban-Americans can be instrumental in helping the Cuban people build successful businesses and mentor them so that they may prosper and avoid being taken advantage of financially, with the understanding that prosperity can lead to empowerment and the ability of the Cuban people to better advocate for themselves and for reforms. On the cultural and educational front, many of us Cuban-Americans (including me) have a lot of “catching up” to do, so to speak. Though we may have been raised “Cuban,” it’s not the same as being raised in Cuba like most of our parents and grandparents. There is a cultural void that I think the Cuban people can help us fill through sharing of their music, arts and humanities. We can in turn serve as mini-ambassadors ourselves to educate the American public and help them understand the real stories, lives, and culture of Cuba, beyond mojitos and vintage cars. In that way, we can perhaps evoke a certain cultural respect for the country that would help to preserve its character. All this, of course, assuming the conditions are politically set for such exchanges, and with the ultimate goal of ensuring real and meaningful changes for Cuba on all fronts.

*

Ruth and Richard: Gracias for reading this interview!

Dear Richard,

Thank you for sharing your provoking thoughts on your search for what is suppose to be the essence of being Cuban.

Even though I came to the United States at age 12 ( in 1962 ) the thoughts of Cuba never departed because I lived my childhood there. But ,at the same time I was very close to the American culture as I attended one of the so called ” American schools ” in Havana ( actually it was founded by the two Jamaican-born British subjects teachers ) – St. George’s School. The bilingual – and up to a certain extent -bi-cultural education I received in my formative years- prepared for life in the USA and upon arrival on American soil in 1962 I felt I was arriving at at a home away from home. So strong was my connection to the US from an early age that the constant anti-US propaganda from Cuba’s communist rulers made me want to disconnect from those things that were Cuban but tainted by the rules of a new order. Of course I missed Cuba , but as the years went by I wanted to regain a sense of ” nationhood” and knew I had to put on hold my ” Cubanness” to give my ” Americannes ” a chance to grow and mature and take a strong hold in by heart and soul. IN May 2002, after a 40 year absence, I went back to Cuba and felt like a fish out of water , a very disoriented visitor in the city I was born , in the country I once called home. Everyone’s trip back – if they go back-is a very personal decision (and a very hard one to make) not to mention the emotional roller-coaster ride you experience. Personally , very personally, I think that if we accept Cuba for what it is TODAY bridges of understanding and reconciliation can be built. I understand – or try to anyway-the pain elder Cubans experience on anything related to Cuba. They lived life there as adults and their view of Cuba is totally different from mine. But once thing is for sure Richard, we can honor, respect and remember the past, but we will never be able to bring it back nor we can rebuild Cuba on the image we had of years gone by. It is sad that so much pain has caused so many family and friends divisions , built so much mistrust ( even hate in some cases ) and have left a wound open that refuses to receive the healing needed so on top on such sufferings a new beginning could rise. I do not know the answer to all this dilemma, but once thing I know for sure, loving with an open heart what we value and respect of the ”

Cubanness” that lives and survives on both sides of the Strait of Florida can have a rebirth if we work hard at it focusing on the many things we have and share as members of the human race.

All the best to you and thank you for all you have done to make reconciliation among Cubans a little bit closer to today’s realities.

Al Martinez, Bedford, Texas

Al:

Thank you for sharing your feelings about Cuba.

I left Cuba at the age of 14 in 1960. I never thought that I would be able to rid myself of the bitterness and hatred In my heart. But two years ago I discovered that forgiveness can heal your heart and allow you to think clearly. Call me a “slow learner” if you wish.

I now travel to Cuba approximately every 4 months where I install water purification systems in churches.

We are all volunteers and the equipment is all paid by donations from the US.

Beautiful! Thank you for sharing your thoughts about this extraordinary moment in Cuban/U.S. history. I love Richard’s inauguration poem, and also his beautiful prose poem,”Havanasis,” which I have used in my literature classes. I’m looking forward to reading “Matters of the Sea,” and am delighted that it is being made available in a bilingual edition, so that the beauty of BOTH languages can be appreciated. I am so happy that in celebrating the normalization of relations between the U.S. and Cuba, the beauty and power of poetry was also recognized on this day. I can’t think of a better way, or a better person, to have chosen to make this special moment in our history even more special.

Congratulatins Ruth and Richard ! You are showing to all Cubans of our generation and others, the true feeling of people that are living in both side: Cuba and USA .

La apertura de las embajadas ha sido un desastre que no beneficia realmente al pueblo de Cuba ni al estado-nación cubano.

Y reconozco que sus planteamientos siempre son interesantes e ilustrativos.

Hay que estar siempre pendientes de lo que ustedes hacen.

Doctora, me inclino muy respetuosamente ante usted y beso su mano.

Muchas gracias por sus esfuerzos.

Dear Mr. Angurel:

The opening of a US Embassy in Cuba is not a disaster any more than our embassy in Russia. It is civilized behavior.

What is a disaster is the Cuban Embargo. How ironic that we, the Cuban Exiles, have made it possible for the Castros to remain in power for 55 years!

The Embargo is the escape goat and the external threat that keeps the Cuban population under the control of the Castros.

I challenge you, Ileana, Mario and Carlos to a public debate on the Cuban Embargo, any time and any place.

Because you are the guilty ones.

Richard:

Thank you for your beautiful poem and sharing your feelings. My feelings about being a Cuban and an American are so much like yours and I feel like you are my brother.

Many years ago I read an article in the Miami Herald written by a Cuban poet. I so much regret that I do not remember his name nor the exact words in the poem. But I remember the message in his poem: La patria es el lugar donde uno primero suena de su primer amor (Your motherland is the place where you first dream about your first love).

Maybe that is why I have never stopped being a Cuban.

I harbored for many years a lot of hatred in my heart for the pain and suffering that I experienced as a result of the Castros. I had giving up ever reconciling with the Cubans that stayed behind and their descendants. But, thanks to my son, maybe he conveyed a message from the Lord, I found the strength and the will to forgive and reconcile.

After a more than 50 years absence from Cuba I know do missions in the island. I install water purification systems in churches, without regard to their denomination. The missions are all made possible by volunteers and donations.

I am also dedicating myself to achieving the lifting of the Cuban Embargo. I want more than hope that the Embargo will be lifted. I want political change in the US, here and now, that will enable the lifting of the Embargo.

That can only happen if, at least, one of the Cuban-American Representatives in the US Congress is defeated in the 2016 election.

I am exploring running against Ileana. I believe that the Cuban-American community is ready to endorse the lifting of the Embargo.

Sincerely,