For Cuban-Americans, visits to Cuba can be especially complex experiences. We’re elated by the company of family, yet feel clandestine. We feel at home, yet estranged at times. We’re natives, yet tourists. We want to enjoy every bit of music, food, and culture Cuba has to offer, but often feel guilty about doing so. Can we have our mojito yet still honor the stories of our exile family and community? In this month’s post, Anna Kushner shares her relationship with the island in this context. With a keen and sometimes humorous eye, she takes a look at the wide spectrum of emotions and contradictions surrounding her various trips to Cuba, especially now as tourism continues to expand. We hope you enjoy the piece and look forward to your comments!

by Anna Kushner

Read post in Spanish >>

Something about the martyred saints thrilled me as a child: St. Lucy’s eyes on a plate, the many arrows piercing St. Sebastian’s side, St. Maria Goretti stabbed eleven times. I wanted to touch their wounds as much as the fruits set out before the large statue of Santa Barbara at a family friend’s house, or the flowers laid out at the Virgin’s feet at church throughout the month of May. The saints were powerful, and I longed to achieve their other-worldliness through my own deeds. Though I could barely be quiet for more than two minutes, I would take vows of silence to test myself. I would read the stories of Catholic zealots who denied themselves food and water or comfortable beds, and would mimic their suffering by wearing too many clothes on a hot summer day. Around age ten, I made up a game: I would imagine what horrors I could be subject to in Cuba if my parents had not chosen to leave the country in the 1960s, after my father had turned against the Revolution he initially supported but before I was born. My imaginings started the summer I saw Huber Matos, a former-revolutionary-leader-turned-political-prisoner, speak at a congress of the activist group Cuba Independiente y Democrática in my native Philadelphia. I had overheard dozens of stories about Cuban political prisoners before then, but hearing Matos tell his story firsthand made an even deeper impression on me, adding to the storm in my mind of all the terrible things Fidel and his men would do to me or to my parents if we ever visited the island.

Anna at Finca Vigía with her sister Alicia and her niece Larisa during her first trip to Cuba, 1999.

While those thoughts scared me, I confess they also bolstered my view of myself as someone noble and resistant, like the saints, capable of enduring a thousand unspeakable horrors, as well as whatever trivialities of my daily life plagued me. So, when I couldn’t go to a sleepover with the americanas from school, or couldn’t join the swim team because our family’s health insurance coverage had lapsed, or when there was no money for the summer camp I desperately wanted to attend, I would plunge into thoughts of how much worse off I’d be in Cuba. Would I be standing in an interminable line, with my libreta ration book in hand, only to be told after hours that I couldn’t eat at all that day; or would I be cutting sugar cane, along with hundreds of other children my age, rats nestling in among us at night in shared bunks, crawling over our exhausted and aching bodies?

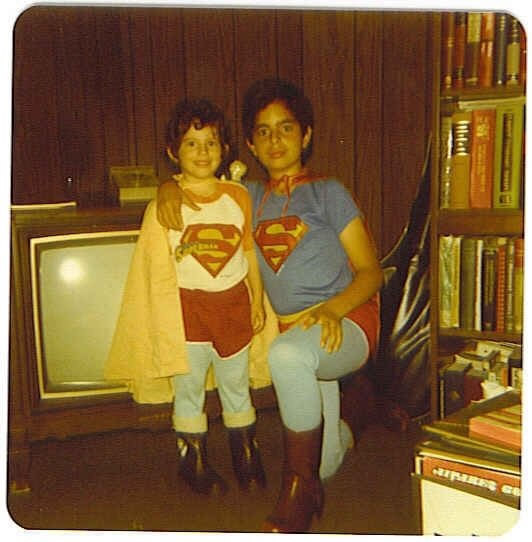

Anna and her brother Alex in the living room of their house in Philadelphia, circa 1979.

Prior to my first visit to Cuba at the age of 23, I had always imagined the worst-case scenario when picturing myself on the island: an official taking one look at my last name and saying, “Your father betrayed the Revolution and now you must pay,” before carrying me away in handcuffs. I rarely imagined myself enjoying a pleasant afternoon in the company of family members who had stayed on the island, or lazily walking along the Malecón. I arrived to a Cuba in 1999 that was only barely past el período especial. A place where, yes, some of my deepest fears were true—food was scarce, electricity was undependable, and water was collected in huge cisterns, then boiled on the stove for bathing and cooking. Hurricane Irene passed through the island during my stay. I watched in horror during the days that followed as buildings swollen with water dried out and collapsed in La Habana Vieja where I was staying. I walked in the middle of the street, avoiding the sidewalks, fearing an old balcón would fall on my head. All this fit my macabre thoughts of Cuba and the tortured lives of saints.

And while there were no men in olive-green uniforms waiting to arrest me because of my U.S. passport or my parents’ assumed transgressions against la revolución, I was always aware of the need to stay silent while on the streets of Havana, to not allow my accent to betray my condition as a foreigner when I was in the company of my Cuban relatives. I dressed in their clothes, as well, so that I wouldn’t stand out, and together, we lamented our inability to enter one of Varadero’s luxury hotels after I’d paid for a driver to take us from Havana to this ocean-side paradise my mother evoked so often in her recollections of Cuba. The hotels, back in 1999, were only for foreign tourists, and I had decided firmly to shed this identity at that time.

During that trip in 1999, I had also undertaken to meet my older sister, who was born in Cuba and didn’t leave when my father did in 1967. I had never met countless other relatives who remained on the island. I’d never participated in the rituals that all the cousins did who spent long, lazy days at my paternal grandmother’s house on the Calle Aguiar and who all now, as adults in Spain, the U.S., and Cuba, had a penchant for the Hershey’s kisses, still available in Cuba during the early days of the Revolution, that my grandmother doled out to them. I did not appear in any of the photos of the cousins taken in the 1970s, when everyone was wearing the same bell-bottomed and plaid-fabric fashions that made their way around the world then. I was not the owner of a marvelous box of family souvenirs that included my father’s various school and professional I.D.s and the photos of weddings of people who were now dead or in exile, but who were mostly unidentifiable to the younger generation in Cuba. I had not previously been aware of how different the light is in the Caribbean, of the smells coming up from the Malecón, of the lure of the Barrio Chino with its cheap pasteles de guayaba, of how wrong I’d been to make Miami a proxy for the Havana of which I’d had no firsthand experience for years. They had little to do with each other, I realized, one city gleaming and new, symbolizing the embarrassing physical comforts I enjoyed growing up; the other city, while revealing itself to me, also making evident the inventory of how much I’d lost already. Havana was nearly tailor-made for my fantasies of martyrdom.

Anna at Finca Vigía with her sister Alicia and her niece Larisa during her first trip to Cuba, 1999.

But I saw no real or imagined suffering during my most recent trip to Cuba, when I attended the Havana Book Fair in the company of other U.S.-based Cuban writers. I was stunned by the sheer number of Americans all over the city, spit out of planes by JetBlue and American Airlines which now offer direct flights between the two countries. I know Cubans can be quite boisterous, but the Americans I saw in Cuba were even louder and more conspicuous. I was dazed by the number of offerings on the menus of restaurants I visited, and surprised by how the waiters no longer recited a long list of everything that was not available as they used to do. I stayed at a casa particular the entire time, instead of with my family, and luxuriated in taking daily showers with running water; and the fresh café con leche served by the housekeeper every morning. I drank all the wine and aged rum I wanted at beautiful bars all over Havana like La Guarida, the terrace at the Hotel Presidente, and la Fábrica de Arte Cubano; and at a reception celebrating the most elite participants in the book fair. It all felt like a fantasy life—not a saint’s life—that was simultaneously enchanting and guilt-inducing for me.

On the day of my arrival to Cuba, I took a bici-taxi and then an almedrón (a shared cab only marginally more efficient than a bus) from my family’s apartment in La Habana Vieja to the casa particular in el Vedado. I then walked 4 blocks with all of my bags in the brutal mid-afternoon heat of Havana. That sweat-soaked journey felt like the “real” Cuba, the one I had come to know and expect over several different visits. But for the first time I experienced another Cuba—the Cuba where I could meet writers and artists whose work provided enough for them to make a fine living (Could I have been one of them?); the Cuba where I could have long conversations with the Cubans I met about something other than the usual topic of resolviendo (getting by); the Cuba where I could hail a taxi late at the night, as if gasoline were plentiful despite the fact that Venezuelan oil subsidies to Cuba were no longer. If Cuba was always this easy and enjoyable, I would visit more often, I thought to myself.

Anna at La Catedral de La Habana with her sister Alicia and her daughter Amalia, 2010.

And for that, I felt terrible. I felt disloyal to my 10-year-old self with her imaginary hair shirt, disloyal to the invisible chorus of exile voices who want me to think of Cuba as poor and backwards, disloyal to my adult self, who has been repeating the same narrative about her relationship with the “Cuba de hoy” to herself, and others, for the last two decades. Could I accept or imagine anything other than feelings of misery and loss in Cuba? Did I have the right to be, dare I say, happy there and drinking wine on a moonlit night como si nada?

The daughter of Cuban exiles, Anna Kushner was born in Philadelphia and first traveled to Cuba in 1999. She is a translator from Spanish, French, and Portuguese. Her translated works include The Halfway House and Leapfrog by Guillermo Rosales (New Directions), The Autobiography of Fidel Castro by Norberto Fuentes (W.W. Norton), Jerusalem by Gonçalo Tavares (Dalkey Archive), and Heretics and The Man Who Loved Dogs by Leonardo Padura (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), among others. Her writing has appeared in The Bucks County Writer, Crab Orchard Review, Cuba Counterpoints, Dzanc Books Best of the Web 2008, Ep;phany, and Wild River Review.

Wow! The feelings evoked through these paragraphs is a sentiment that only a Cuban-American can truly understand. My parents came to the states when I was only one. I was born in Havana, yet only in name was I really Cuban. I married another Cuban-American, and with our two daughters traveled to Cuba right before the pandemic broke out. The land where my parents were born, and their parents before them. The land were they courted, danced the nights away, married and had two children. The experience left me speechless. What to say about a place that hold all your families joys, history, stories, and secrets? What to say about this forgotten land that sits all alone surrounded by water and stillness? I too felt guilty as I enjoyed the food, the outings, the lazy afternoons drinking cafe con leche…as the natives were “resolviendo”….their deep set eyes with worry and sadness would speak to us. It was bittersweet to visit Cuba. It was an unforgettable three weeks of beaches, music, and languishing with the friendliest most affable people concentrated on that prison island. A little part of me was left behind when my parents emigrated, though I was too young to know, and a little part of me was left behind, this time knowing, when we flew back home last January. Cuba has something special, something mysterious, something that calls to you, envelopes you and hypnotizes you. Yes it truly does!