Going to Cuba to pay a visit to the dead who rest in cemeteries on the island has become a common ritual among Cuban Americans. In the essay “Last Rites,” Carlos Rafael Gomez movingly recalls finding his great-grandmother’s tombstone at the Colón Cemetery with the help of a cemetery worker, who simply tells him, “I know how important family is.” That is when Carlos realizes he needs to offer last rites to honor the memory of his father, who left him with a legacy of silence and sorrow about Cuba. We are glad to feature this beautiful piece by Carlos, who traveled to Cuba for the first time in July 2017, on a CubaOne Foundation trip focused on literature and the arts, which we led together. CubaOne offers young Cuban Americans the unique opportunity to travel to Cuba on a first visit and learn about the history and culture of the island through immersion in everyday life and close interactions with fellow Cubans who share mutual interests. We were impressed by the deeply emotional stories that emerged among the participants on this trip and look forward to featuring other essays in the future by CubaOne alums.

Abrazos,

Ruth and Richard

by Carlos Rafael Gomez

Read post in Spanish >>

In June 2017, three weeks before I traveled to Cuba for the first time, I received a package in the mail from my older sister, Mariela. It was my dad’s journal, which I’ve known about since he died but had never read. It’s filled mostly with work notes and contacts, but one of the entries is the beginning of a story based on his grandmother—my great-grandmother—Berta Arocena de Martínez Márquez.

My great-grandfather, Guillermo Martínez Márquez, and great-grandmother Berta Arocena de Martínez Márquez

Entitled “Last Rites,” the story begins on the deathbed of the narrator’s grandmother. Portrayed as stubborn and deeply committed to indigenous Cuba, she refuses the priest’s absolution, knocking over his vial of oils when he answers her last question on earth—“Are there Spaniards in Heaven?”—in the affirmative.

“Then let me go to hell!” she says. “At least I can see the Spaniards there suffer!”

Mariela called the next day to see if the journal had arrived, and we talked about our dad and great-grandmother. Neither of us ever met her—nor did my dad, for that matter, as she died two years before he was born—so it’s easy to take the fiction as fact, especially since the broad outlines of her character conform to what we know: that she was born in Cuba, that she was stubborn and principled, that she had a Galician accent.

Mariela said that our dad always identified with his grandmother, or at least with her depression. How every year she would fall into months-long spells, nearly comatose in her rocking chair when she wasn’t sobbing in front of the air conditioning unit. How she described her mind as a mess of wires and a tangle of hair, the resultant electroshock therapy as a comb that straightened it out. How she repeated the cycle nearly every year until she died in 1956.

When I got to Havana, I tried to find her house, where she raised my grandmother and where my grandmother, in turn, raised my dad for the first two years of his life. “Calle 27 entre 22 y 26, número 2210,” I said to the driver, reading the address my grandmother, also named Berta, gave me. “Miramar o Vedado?” he asked, and when I said I wasn’t sure he consulted his friend, who hopped in the car—a ‘58 Buick, I was told—to confirm that two neighborhoods in Havana have those cross streets. I chose Vedado, as it was closer, and five minutes later I was on a cobblestoned street where no one had heard of number 2210. The houses were in the 600s, and when I tried to chase them up, I was stopped short by a yellow wall. It was Colón Cemetery, one of Cuba’s most famous architectural sites and the purported resting place of my great-grandmother.

My grandfather Julian Rafael Gomez and grandmother Berta Martínez Gomez

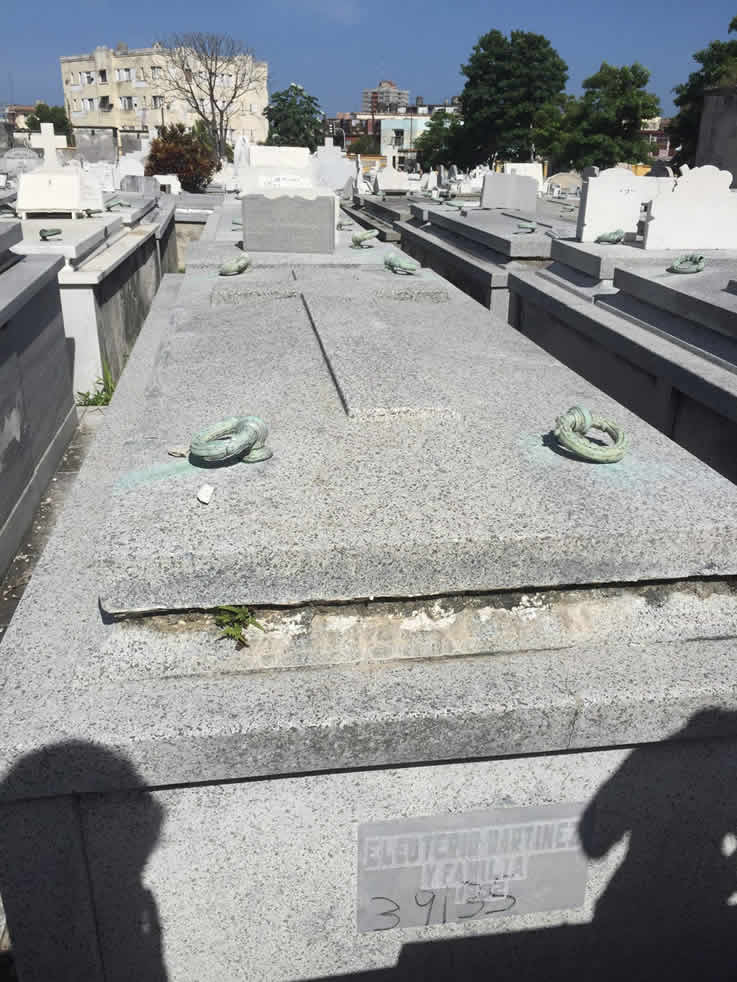

My dad’s cousin Ani recently told me that when she first went to Cuba, in 2005, an attendant at Colón recognized her grandmother’s name and led her to what he promised was Berta Arocena’s burial plot, unmarked, below a tomb marked for “El Euterio Martínez y familia, 1952.” My grandmother doubts her mother is buried there, at least not anymore. She told me that Castro exhumed most of the bodies when he took power, as private cemeteries were antithetical to communist ideals. She said this with a slight but deep-seated bitterness, ignoring entirely the other explanation: that several years after burial, it’s customary in Catholic cemeteries to move the bones of the deceased to an ossuary. Either way, the plot may be empty if it hasn’t been repurposed.

When Ani visited Colón, she took two photos of the gravesite and they were my only references for finding it. I was looking for a white, stone sarcophagus with cast iron pulls and a cross relief etched into the top; and Colón, I discovered, is a 140-acre grid of white stone sarcophagi with cast iron pulls and cross reliefs.

An hour later, my shirt and shorts soaked through with sweat, three men more familiar with the cemetery were passing around my phone as they bickered over the scant clues in the photos: the buildings in the background, the approximate distance from them that Ani was standing, the degree to which the vegetation between the two would have changed since 2005. Eventually, I called off the search and left my email address for one of the men, Ramses, who said he would try again that evening. I urged him not to—“No estoy seguro que es su sepultura”—but he was determined, saying he had a friend who worked in the cemetery’s records office and might be able to help after-hours.

My dad doesn’t have a sarcophagus or a tombstone. He was cremated, and Mariela went alone to our old house to scatter his ashes beneath the Japanese maple. He planted it when I was born—June 13, 1991—which turned out to be nineteen years to the day before he would die.

The next day I had an email from Ramses. He had found the correct plot, and when I met him at the cemetery he gave me a mixed bouquet of flowers—ivory, magenta, ochre—to put on it. “I know how important family is,” he said in halting English, and I thanked him in halting Spanish as he led me through the rows of identical tombstones. When we got to my great-grandmother’s, Ramses told me he would give me a moment alone. He repeated: “I know how important family is.” I didn’t tell him that I’d never met my great-grandmother and was mostly there for my dad. The sentiment applied regardless.

Ramses and me

The week before, as I had gathered my bags to leave for Cuba, it occurred to me that I should bring something of my dad’s. He never returned to the island, so I tore a page from his journal, folded it into quarters and stuffed it in my pocket. It went with me everywhere that week: the plane to José Martí airport and the ferry from Regla, the ’58 Buick and the gravesite that probably isn’t his grandmother’s, which I kissed and placed the flowers on anyway. Finally, on the day I was set to leave, I took it to the house he was born in: number 2210 on Avenue 17 in Miramar, not Vedado. There was only one more thing I needed to do.

A sinewy man with white hair sat on the front stoop, and I apologized for bothering him, explaining that had been my family’s house. “Martínez Márquez?” Without getting up or speaking, he pointed to a small plaque that said “Cristobal Martínez Márquez – arquitecto – 1911” and gestured vaguely around the property. I took this as an invitation to look around but not to go inside.

The house is cream and rose-colored with red Spanish tiles, and there’s a mamey tree that shades most of the courtyard. My grandmother told me that my dad used to play out here, and it was strange to imagine him tottering over these tiles as a baby, fleshy and wide-eyed and unaware that in 52 years he’ll have had enough of his life to end it.

2210 Avenue 17 in Miramar

When my dad died, I didn’t go with Mariela to scatter his ashes because his funeral had been enough of a ceremony for life willingly thrown away. Another felt pointless, like putting flowers on top of an empty grave.

Seven years later, I pulled out and unfolded his journal entry, dated April 9, 2009—a year, two months and four days before he died. The ink had bled along the creases, and the paper itself was stiff and wrinkled from days of dried sweat. I knelt down and placed it on the hot stone, making sure I was alone before I set it on fire. There was barely any flame, just a glowing line of ember that advanced up the page, curling it in on itself like a dried leaf. The page collapsed when I tried to pick it up, so I blew the ashes into the air, where I watched them float and scatter and disappear.

Carlos Rafael Gomez is a writer living in Los Angeles. Originally from Charlottesville, Virginia, he graduated Yale University in 2013 with a degree in English literature and creative writing. His work has been published in Cutthroat, Whurk and other publications. He is currently working on his first book, a memoir about his father.

hola, me gustaria poder tener fotos de Berta Arocena de Martínez Márquez., soy poeta y escritor, tengo escrito un libro titulado El Lyceum Y Lawn Tennis Cub: su huella en la cultura cubana. ahora estamos preparando su segunda edición, Berta fue fundadora de esta institución femenina y feminista.