We associate José Martí with the palm trees of Cuba, but in fact he spent many years of his life in New York getting to know the maple and the oak trees. It is a pleasure to introduce readers to this other side of Martí’s sensibility through Emma Otheguy’s lyrical essay, “José Martí and Autumn Leaves.” We think you will never see Martí quite the same way again after reading her words. Because it’s so important to pass on our love for Martí to the next generation, be sure to have a look at Emma’s beautiful bilingual children’s book, Martí’s Song for Freedom/Martí y sus versos por la libertad. We hope you enjoy Emma’s piece!

Abrazos,

Ruth & Richard

by Emma Otheguy

Read post in Spanish >>

When autumn came to our little town outside of New York City, my mom liked to tell me that if my grandmother, who was a painter, were in New York, she would want to paint the leaves. It was an unusually romantic statement for my practical immigrant mother, and it always surprised me: somehow, my grandmother and the autumn leaves didn’t fit together.

There was the simple incongruity of any Caribbean person away from the sun—but it was more because I understood my grandmother as separate from the Northeast, from English words and autumn leaves. My grandmother was born and raised in Cuba, but by the time I met her she was living in Puerto Rico, and I came to associate her with what I knew to be common between those two islands: humid air, lush green, blue water. The senses of the Caribbean, the colors and the temperature and the movement of the trees seemed irreconcilably far from my life in New York, and even farther away in the fall, when New York was filled with brown and crimson. When I thought of my grandmother, I thought of the Spanish words, the coquís and the palm fronds that filled our visits to Puerto Rico. My life in New York was separate⏤it was a life of school and friends and crisp weather and it had, to my mind, nothing at all to do with summer in the Caribbean.

When my grandmother visited us one October, that sense of distance between New York and the Caribbean became harder to maintain. My grandmother gave me drawing lessons during that visit, and I gobbled up her instruction because in seventh grade I was desperate to learn anything and everything creative. She had me sketch our house, and I would sit on the sidewalk and draw, then rush inside to show her what I had done. She would point out details that I had missed, like the orange pumpkin on the steps and the shadow between each clapboard. When she talked about the light on a pumpkin waiting to be carved, it became harder to separate her from autumn.

Just as my grandmother’s autumn visit made space for the possibility that one could belong to both palm trees and oak trees at once, learning that José Martí had lived and worked in New York opened my heart even further. I was working in upstate New York when I first learned that Martí’s Versos sencillos, the words I had memorized as a child and heard sung in “Guantanamera” again and again, were written in the Catskill Mountains of New York State, not far at all from where I was working. It seemed as if whenever the Caribbean felt far away, it came and found me, and offered new possibilities for connection. The writing of my first picture book, Martí’s Song for Freedom, was born from this connection, this desire to bring the poet and hero of my parents’ homeland to the kids who surrounded me in New York. These were kids who knew the landscape Martí praises in Versos sencillos inside out, who knew all about Jean Craighead George and Rip Van Winkle but not about José Martí. I knew they would love the drama of his life and the clarity of his vision for social change.

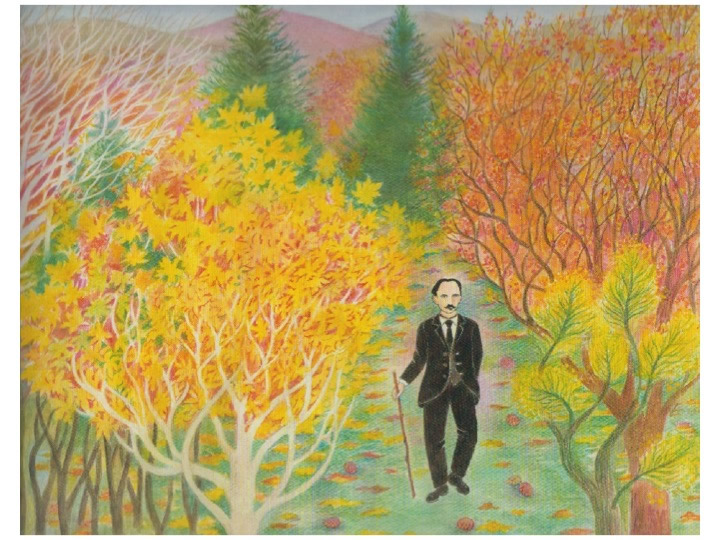

I learned from my grandmother’s drawing lessons that perspective is the willingness to draw what we actually see and not what we know to be true, to draw the curve of the glass on a table even when you know the bottom to be flat. My grandmother passed away last year in Puerto Rico, but I like to think she would have liked Beatriz Vidal’s illustrations of my book, especially the one of Martí in the Catskills, walking amid the autumn leaves. I hope that Caribbean kids living in the Northeast of the United States pore over that page⏤I hope they look at it for as long as I have looked at it, and that it makes them feel, as it makes me feel, that they belong here.

Art by Beatriz Vidal. Used with permission from Lee & Low Books.

I’ve known for as long as I can remember the stanza in which Martí writes:

“Mi verso es de un verde claro

Y de un carmín encendido:

Mi verso es un ciervo herido

Que busca en el monte amparo.”

“My song is the palest green

And the fiercest crimson:

My song is a wounded deer

That in the countryside, seeks safety.”

But now when I hear this verse, I see the autumn leaves, and I see Cuba and New York knit together by Martí’s words of longing.

I know that if my grandmother had ever painted those autumn leaves in New York, she would have wanted to see the leaves the way they really are, as Beatriz Vidal has painted them: dotted with Cubans from the land where the palm trees grow. This is not a clever thesis or comfort for a displaced Cuban family, this is the world as it really is, as my grandmother would have wanted it:

José Martí, and autumn leaves.

Emma Otheguy is a children’s book author and a historian of Spain and colonial Latin America. Her picture book debut, Martí’s Song for Freedom, has received starred reviews from School Library Journal, Booklist, Kirkus, Publishers Weekly, and Shelf Awareness. She is a member of the Bank Street Writers Lab, and her short story, “Fairies in Town,” was awarded a Magazine Merit Honor by the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators (SCBWI). Otheguy lives with her husband in New York City.

0 Comments