In this dreamy and poetic piece Yosie Crespo beautifully evokes the themes of myth and memory that crest like a wave into the heart of the reader. She takes us back to her childhood home in Las Canas, Pinar del Río, Cuba—not only through her gorgeous language, but also through the words of other writers she admires, and through a compelling series of photographs that add to our understanding of place and her emotional journey. Even though Yosie is bilingual, she chooses to write in Spanish, which make us think of our linguistic affinities and loyalties—how we choose to experience, remember, and express ourselves differently through different languages. In David Frye’s translation, Yosie’s words come alive in English, creating another country of hope for one who returns.

Enjoy,

Richard Blanco and Ruth Behar

by Yosie Crespo

Read post in Spanish >>

It lay in my memory

—like, in a sealed coffer,

a precious stone.

It glittered within there, hidden,

illuminating the opaque face of things.

—Rosario Castellanos, “The Missing One”

More than twenty years could have gone by, easily. A few minutes ago it was nineteen ninety and I was sitting at the kitchen table where Abuela was straining the last drop of coffee from the last harvest. I was just a girl of ten then. And the thing is, something like time recurs without our noticing behind our backs that it’s watching us and it becomes blind obedience on the pathways of the days that lead only to oblivion, that myth.

More than twenty years went by and I needed that myth to learn how to live in another country, one that gave body and soul to this other me (incomplete) until the time came to celebrate my thirty-second birthday, which meant three things:

It was already time to return

It was time to return

Time, return

Until that moment, the missing one, and I had needed that myth to live. We lived for the myth. We both created an intelligent, entertaining story, more or less well-told, with hidden passages and a tiny key. We managed to erase and reconstruct lines from childhood memories (something that can at times be very serious), fakes, videoclips, brief retellings that we gave form to through books—literary maps of cities and names I didn’t know; crumbs, but so clean you could eat off them, and so I did.

After decades of chasing down an ever-young memory, I went to Havana in search of a good script and a specific speech. Don’t die without a labyrinth, Lorenzo García Vega once cried, you’ll have to face the color. And I, eager to learn, yearned to seek in the contemporary writers of the moment for men and women like myself, and in books that consequently were beyond my reach for a long time. I asked a friend and he told me: one returns to satisfy a parasitic need, or to reconstruct oneself.

It happened almost like things do in dreams. After the first few friends, many more came, and the literary circle grew larger and larger—so large it was scary. Disorderly, brilliant writers with hair that tasted of the sea, writers whom nobody knows, whom everybody knows, who have nothing to do, who do everything and then leap into the void, with short names, some with immensely long names. All sorts. It was like they were emerging from the dust and multiplying.

I got knots in my stomach and in my throat when I returned to the beach of my childhood. It would be difficult to exaggerate the reality, that is, let’s see if I can explain what I mean without my imagination painting scales on my tongue: it didn’t exist.

And it’s not like Las Canas was ever a big deal; it was literally known for its swampy land, scanty black sand, and water filled with jellyfish that nobody could escape, and today only traces of its splendor remain, the bones of the houses that endured the August heat with inert resistance. It most resembled a battlefield in the process of extinction, and over my head, a ramshackle labyrinth.

—Who took my beach?

—It was the hurricanes, and then everybody left, they each went in different directions and I stayed: because somebody always has to stay.

We are all living on stolen land.

—Marlon Brando

Beach, Las Canas, Pinar del Río, Cuba.

Coordinates: 22º 13´ North, 83º 36´ West.

A bit farther north stood the house. Hardened as if it weren’t mine, far from the things that make you happy. There it was, like a truth adhering to your body, almost a permanent syllable—there—like the image of a man who has died. I sought its heart to soothe it, to return to the nest, to come within, to what is mine, this was something I kept repeating to myself with such utter naturalness because above all other extremes I yearned to find within that chaos the order proper to the things that belong to me.

That very afternoon they gave me something reminiscent of what happens when we dream, me or the other part of me that was unfolding, and still keeping a watchful eye on a wall in the living room.

I surveyed it in exhaustive detail, I remember embracing the image as we do when we meet an old lover until we can find the right words to say. Later that night I wrote in my diary:

Photo of Yosie in Cuba, 1983

before my eyes something I cannot name, the essence of a being that tells me something more intimate and more personal than any other memory, what is it saying, this portrait that at once enchants me and saddens me. What do I do with you now, You who have traveled to eternity in search of yourself.

And moment by moment the sweetness of the guarapo, the sugar-cane juice, would return, the scent of the kindly grains, people I knew from before and who treated me with the naturalness of someone who knows I live there. Because the land belongs to the one who returns, and when you are thinking of returning it’s because you never entirely left.

It was like learning to recognize my country in its true depth with new eyes, and as few relatives as I had left, there were reasons that went beyond myself for returning a second time. Missing the sun, the air, the city’s noise, and the solitude you can only understand when you’re listening to a Silvio Rodríguez song in the middle of a packed bus stop.

My new friends understood me without my having to explain myself constantly and while I talked about getting the books from inside they asked me for books by Orwell, by Hermann Hesse, by Lispector, and between us all we experienced a sense of nostalgia and belonging that couldn’t have been programed or learned. Between words and utopias we decided how to fix our worlds, in which of course everything began and ended with a broader internet connection and a desire to see each other more often without having to wait so long between times. And it was good being able to talk about a morning that also had something to say about me.

More than half my life had gone by living outside of Cuba and yet the sense of belonging overwhelmed me. It must be the warmth of the embraces, that profound closeness in the way its people look at you and infect you with laughter, that getting carried away by its colors in its sense of humor that can deal with any adversity.

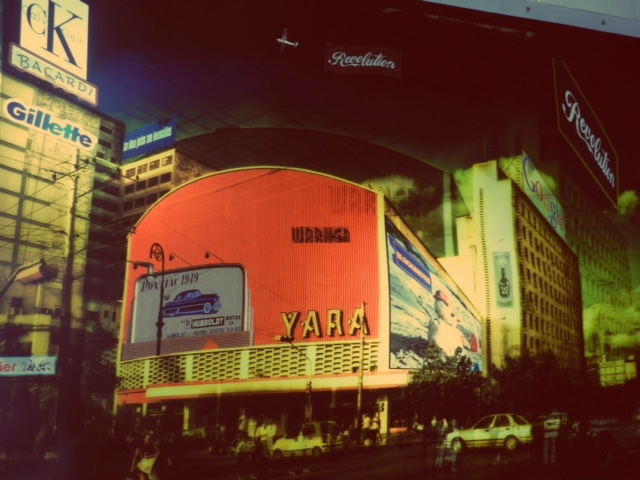

Havana with its narrow streets full of potholes, façades in ruins, and tourists with little cameras managing to capture the bright color of its grime, doing academic studies of how much longer it will all last in its natural beauty.

But I hadn’t returned in order to decode Cuban reality or to understand things that are fairly incomprehensible, and if I obey only an impulse to seek it is solely found in the contagion of faces that are living apart from the speeded-up life of the big cities and don’t have any need to worry about the Dow Jones, and the panorama—colorful though it may be—floats through glimpses of emotions where nothing is hidden, and a new generation that is moving ahead toward hopeful paths to a still-mysterious future refuses to see stains in the stains.

I spend my last afternoon watching the Malecón while listening to vinyl records, another way of nourishing memory is through music and the sea, the clouds, cotton candies contributed to the feeling of distance: a genuine prophecy. It was as if from that very moment I was beginning to embark on the long road of return, and I wrote:

The sea twitches and I’m a little girl in a blue dress

reading between the lines that say:

we’ll have to leave those plants behind,

and that sweet estrangement of identifying what

the simple life was

with its knives and its bones

the bellstring of the house and its hymns

left me this way,

and like men destined for gardening

I’ll do the same:

cultivate you in the perfect spot for you to bloom

on days when forgetfulness carries a compass

on nights when its lights blind me.

those who return are never the same

—Milho Montenegro (young Cuban poet)

I didn’t say goodbye to anyone because that was a glorious day where everything was charming and made sense: in the process of searching I met more than one improved version of myself and of a city that would change faces possibly with each return.

I packed a little food in my knapsack in case the trip went too slowly and went once more through the beautiful images that I had recovered and that ended up distressing me. It must be because I was born in a country sick with nostalgia and there’s no possible inoculation that could cure me.

It’s been eight trips now since my first return, and as of last month I’ve been in this country for twenty-six years, which means only one thing: My bags are packed and I’m ready to go. Es hora de volver.

Yosie Crespo, 2016. Translated from the Spanish by David Frye. A translator and anthropologist who teaches at the University of Michigan. He has translated more than twenty books from Spanish to English, including the novels Simone by Eduardo Lalo (University of Chicago Press) and Planet for Rent by Yoss (Restless Books).

Yosie Crespo was born in Pinar del Río in 1979. She is the winner of the First Prize for “New Values in Spanish Language Poetry” for 2011 from Editorial Baquiana and the Centro Cultural Español en Miami and the Prize for the IV Federico García Lorca Youth Poetry Contest in Spain, 2011. She has published three books of poetry: Solárium (Baquiana, Miami, 2012), La ruta del pájaro sobre mi cabeza (Torremozas, Madrid, 2013), and Caravana (Ediciones El Quirófano, 2015).

0 Comments