Observers of Cuba have noticed there’s a “new Cuba” rapidly taking form. In Havana, which is the primary destination of most American tourists, reservations are required at iconically chic restaurants like La Guarida, and American hipsters are omnipresent on the cobblestoned streets of La Habana Vieja. Vanessa Garcia, who recently returned from a trip to Cuba, wonders whether all these Americans tourists are a blessing or a plague. We are delighted to feature her perceptive piece, which offers a fascinating look at how socialism and capitalism are colliding on the island today. Hope you enjoy Vanessa’s piece and we look forward to your comments!

by Vanessa Garcia

Read post in Spanish >>

In Old Havana there’s a dog—a dachshund—who really hates Trump. At the sound of his name, he growls and shows his teeth: Grrrr. When you mention Obama, however, he becomes docile, head on his owner’s chest, cuddly. He does this again and again, on command; his owner, a Cuban, has trained him to do this. It’s clearly an act targeted toward the new wave of American tourists encountering the island of Cuba, a phenomenon I recently witnessed firsthand.

I just returned from a four day visit to Havana, a city whose pulse I’ve been monitoring from afar since I was a child in Miami. I’m an “ABC,” an American Born Cuban, and so I’ve always found Havana to be at the heart of my own identity and existence. I first heard stories of Cuba through my exiled parents; and later, in the 90s, through the Cuban rafters who would arrive in South Florida starving, sunburnt, and desperate.

These days, I monitor Cuba more closely than ever—not secondhand from afar, but with my feet on the Cuban ground. I’ve been to Cuba three times since 2014, and every time there are changes to record and unravel.

This last visit I was struck by how easy it is to get to Havana. I no longer had to travel on a chartered flight that only Cubans, Cuban-Americans, and people with special licenses could board, as I had to do the first time I flew to Cuba in 2014. This time, I didn’t have to arrive at the Miami airport five hours before my flight, or compete for space with all the other Cubans carrying mountains of aspirin, clothes, appliances, and other “gifts” for their families. This time, I was on an American Airlines flight, just like any other international flight, replete with tourists.

It’s no secret that tourism has been on the rise in Cuba. In 2015, 3.1 million people visited the island, approximately 148,000 of whom were American. Thanks in part to American Airlines and JetBlue, which started offering direct flights to Havana in September of last year, the number of tourists increased to 4 million in 2016.

Photo credit: Ruth Behar

The morning of my flight, I boarded the plane wide-eyed and optimistic; reaching my roots, after all, was now simpler than ever. My body began to fizzle with the same electricity that always fills me whenever I go to Cuba. But then when we landed in Havana, nobody clapped. My heart sank.

You see, there has been a long tradition of clapping when you arrive in Cuba from Miami. A sonorous applause right from the gut, a symbol of elation, relief, happiness, home. The Cubans, Cuban-Americans, and ABCs that used to clap understood the endless invisible miles that were somehow folded into the mere 228 miles between MIA and Jose Martí International Airport. Somehow, that context was now lost. And this seemed both sad and dangerous, while at the same time simply signaling the rise of a new era.

The second thing I really noticed was the amount of English I heard on the streets of Vedado, the neighborhood where I was staying, and where my mother was born. The flood of American hipsters roaming the cobblestoned blocks of La Habana Vieja. The number of people I recognized from the U.S. on my flight to and from Havana.

The looming question: Are all of these American tourists a blessing or a plague?

Ask any Cuban on the street trying to sell Yemayá’s benediction, or a drive in their Almendrón (the slang term for the big American classic cars from the 50s), and they’ll tell you they’re thrilled about the tourism. “Let them come. The more the merrier.” The more Americans that land in Havana, they explain, the more Cubans can eat, build better shelters, buy homes, start businesses, and share the wealth.

Ask the Americans, however, why they are visiting Cuba and what you’ll hear, over and over again, is that they want to “disconnect,” to see Havana “before it changes.” The irony is, of course, that they are themselves changing Cuba in real time, whether they understand that or not.

There’s more to the irony. Americans are able to “disconnect” in Havana, give themselves a vacation from the overwhelming mania of headlines they experience back home, because Cubans have very little access to the Internet. Cuba is Wi-Fi quiet, except for shoddy signals that the government allows in certain parks, where Cuban millennials huddle, trying to reach the outside world, hungering for the same connection American hipsters complain about having too much of.

Ever ingenious, Cubans have circumvented the lack of connectivity by creating a weekly “paquete” or “package” of media—film, music, TV (keeping porn and “political content” out), which they download onto hard drives and CDs and then distribute. As such, they can catch up with what happens outside the island. The package is huge—about 1 terabyte of data, gathering all kinds of genres, from magazine articles and literature to superhero movies. It’s the next best thing to unlimited Internet access.

In Havana, these two extremes are colliding (or are they merging?). Americans escaping the obese capitalism that has led us to Trump (Grrr), and the Cubans, who are trying to escape the extreme socialism that has starved and denied them of information and nourishment, both of mind and body.

What Americans are buying when they arrive in Cuba is the third-world as commodity, within close distance of the U.S. (the escape hatch, in other words, is near). This is a place Americans can drift above, but not weave themselves into, while Cubans reach out for the trickle-down of America’s excesses.

The jury is still out regarding what will come of this merger/collision. Perhaps that dachshund will eventually be trained to Grrr at the word “American,” just as Fidel had trained his people to do after the excesses of American-run puppet regimes, pre-revolution. It will all depend on how carefully Americans tread, how much history they decide to connect with as they unplug in Havana. Maybe Americans can learn to clap when they arrive in Havana. No, that’s worse. Too close to communist conditioning.

The moment that drove home all of these complexities for me was when I used the restroom at La Guarida, one of Cuba’s hippest dining hotspots for tourists. It’s been around since 1996, and gained popularity because of the film Fresa y Chocolate (1993), which was partially filmed there.

The film centers around a straight-laced Cuban revolutionary student named David, who meets Diego, a free-thinker, disillusioned with the regime and the way it treats him as a gay man. The movie turns out to be a touching story about friendship, but it’s also about the trials, tribulations, and glories of two worlds coming together, just as they are coming together now in Cuba, and inside the walls of La Guarida, once more.

When you first arrive at the restaurant, located in Centro Habana, you are greeted by a chipping mural of Camilo Cienfuegos, one of the early revolutionaries who fought alongside Fidel, and who later “disappeared.” As you ascend a set of stairs, crumbling in “romantic” decay, you read the writing on the wall, literally: Fidel Castro’s famous propaganda slogan, “Patria o Muerte!” “Homeland or Death!”

Through the mildew and the dirt, the pentimento of days gone by, you keep climbing. Until you reach a broad, empty room with arches. When we arrived that evening, the rosy rust of sunset was seeping through the space—Havana’s particular light.

After another set of stairs, we reached a rooftop bar. At the edge of the bar, the owners had suspended a white frame that created a border around the city’s skyline. The frame pushed our gaze out over the cityscape—once again, we travelers were not inside Havana’s web, but instead suspended above her. iPhone cameras followed the frame’s slick lead, including mine.

Once seated at our table, the menu offerings were chic and varied: international Cuban cuisine, lamb masala, tuna marinated in sugarcane and coconut, suckling pig in an orange honey reduction. Even lobster (once outlawed for sale within Cuba) for 20 CUCs, which is the equivalent of what some Cubans earn in a month.

There is even a spot in the restaurant (which was Diego’s room in the film) decorated with ephemera from the movie. As I looked around and ate that night, I understood our taxi driver, who had snubbed his nose earlier that evening when we told him we were going to dine at La Guarida. “Ugh…fake,” he said, rolling his eyes. A portrait of Havana, framed.

That was when my mind began to spin: On the surface, the need to package the experience of fine dining in commodified decay, in order to enhance palatability and delight, seems like a capitalist exercise. But when you look at it from another angle, this framing is also very much a part of the communist ethos that wants to control what you see, what you know, what you can access and think. When the two systems reach their extremes, it seems, we escape capitalism only to meet communism, coming full circle. Perhaps the question to ask is: What does it look like in the middle of the circle?

Toward the end of the evening, I made my way to the restroom. Which was also very trendy. A big communal sink in the center, towels hanging like an art installation on the wall. Considering that everywhere else in Cuba you pay about a quarter for a single piece of toilet paper, if you’re lucky, this felt decadent.

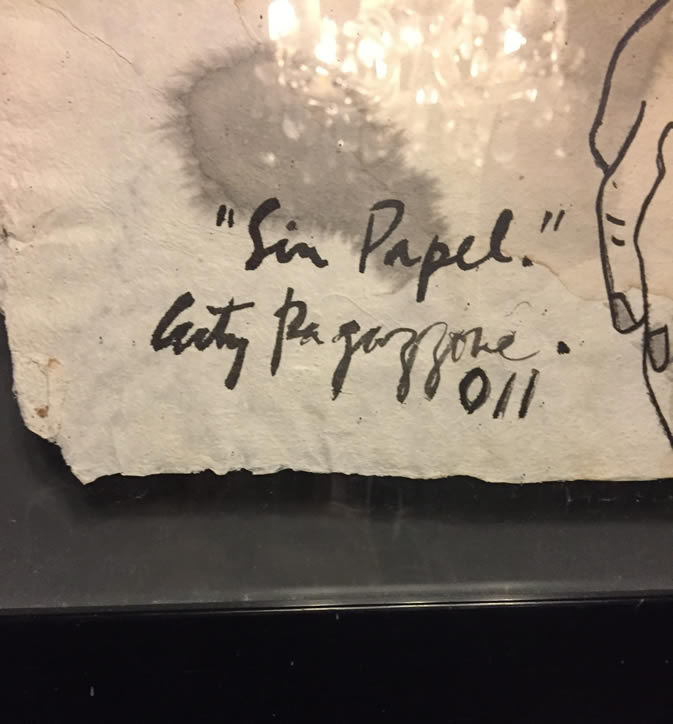

On the wall, however, a reminder. A watercolor of a woman squatting, hovering over a toilet, naked. Behind her, in the image, an empty roll of toilet paper. The piece was entitled: “Sin Papel.” “Without Paper.” We, at La Guarida, were certainly not going without paper, but many of us still have aunts and cousins in Cuba who take showers out of buckets, and scour the city for toilet paper on a daily basis.

On the one hand, I was happy to be in Havana, at La Guarida, sharing with Cuban-American and American friends alike. It still felt very special and historic, the beginning of a process, something which Obama allowed the space for by creating an aperture (no wonder the dog practically puppy-purred at his name). On the other hand, I felt a constant tug at my chest, almost a sadness—a reminder that the process of change is hard, and often expensive.

The website for La Guarida says: “Welcome to my hideaway…not everyone is welcome here.” This is what Diego says to David in the movie when he invites him into his home, filled with censored books and illegal worship. You can see the allure for Americans in that statement—the hipster forever in search of the “underground” in a world where everything is on the surface, in your face. But is this at the expense of the average Cuban, who can’t afford to come inside and who lives in a perpetual underground, always longing to reach the surface, forever hovering over the toilet, “sin papel”? Maybe, maybe not. It all depends on how many people even notice the watercolor on the wall of La Guarida’s bathroom, and how many stop to think about what it might mean. To do so, you have to look closely and read the title, which is in Spanish. It’s then that the image will turn. Suddenly, the woman on the wall isn’t just a naked woman to be gazed at, she’s a naked woman in need, one that’s alive in a real story and on the street outside the restaurant.

How we see that woman will make all the difference in how we extend our hand. In the kind of bridge we build to Cuba and back again.

Vanessa Garcia is a multidisciplinary artist working as a novelist, playwright, and journalist. Her debut novel, White Light, was published in 2015, to critical acclaim—named one of the Best Books of 2015 by NPR, Al Día, Flavorwire, and numerous other publications and institutions. As a journalist, feature writer, and essayist, her pieces have appeared in The LA Times; The Miami Herald; The Washington Post; The Huffington Post and The Guardian, among numerous other publications. She holds a PhD from the University of California Irvine in English/Creative Nonfiction.

0 Comments