As summer starts to fade away, we are delighted to feature an essay on our blog by the distinguished scholar Jorge Duany, who writes eloquently about the shift in his identity from Cuba-Rican to Cuban-American. After leaving Cuba as a child, Jorge grew up first in Panama and then in Puerto Rico. Memories of his grandmother, Mañe, who stayed in Cuba, kept him connected to his native land. He studied anthropology in the United States, then returned to Puerto Rico to teach and lived most of his adult life there. Five years ago, he became the director of the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University. He now lives in Miami, where he is reencountering his Cuban roots in the city he calls “the crossroads of nomads.” His essay reminds us that our diaspora journeys are complex and diverse and take us on many roads back and forth and beyond the Island. We hope you enjoy Jorge’s essay. We look forward to your comments!

Abrazos,

Ruth and Richard

by Jorge Duany

Read post in Spanish >>

Since I was a child, I’ve been troubled by the constant question, “where are you from?” I usually answered, “I was born in Cuba, but I grew up in Puerto Rico.” I have often declared—half seriously, half in jest—that I am “Cuba-Rican.” However, those answers never settled which country I felt most attached to, a question that became periodically urgent, as when Puerto Rico’s national team faced Cuba’s in basketball or baseball competitions. I still have to think twice when I see the flags of the two countries, with their identical layout and inverted colors, before deciding which is which. Somebody recently told me that the Cuban flag has the star within the triangle that is red like a heart and that is how I typically solve my confusion.

I was born in Havana, Cuba, in January 1957, just two years before the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. Thus, practically my entire biography is a historical byproduct of the Revolution and the continuous exodus it generated. I left Cuba in December 1960 with my mother and older brother for Panama, where my father had settled months before. During the summer of 1966, my family relocated to Puerto Rico, where I spent the rest of my childhood and adolescence. I later pursued my university studies in the United States, going home to Puerto Rico during summer and Christmas vacations for almost a decade. Upon earning my doctorate, I returned to Puerto Rico, where I lived until 2012, with a few short stays in the United States. However, five years ago my professional and personal situation took a new turn: I accepted an offer to direct the Cuban Research Institute at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami.

Here I sit on my mother’s lap, surrounded by my grandmother and older brother, in Havana in the later 1950s

Since moving to Miami, my relationship to the Cuban exile community has intensified, while my links to Puerto Rico have attenuated (although I still follow Puerto Rican affairs from a distance). I now read fewer online newspapers published in Puerto Rico; I follow more closely the news from Miami and Cuba. I use Puerto Rican colloquialisms more sparingly than before, such as Ay bendito (“Oh my God”), candungo (container), or bregar (to deal with); and I change the gender of Spanish words like batida to batido (milk shake), to follow Cuban custom. I still prefer medium-roasted coffee from Puerto Rico, rather than the strong dark coffee shots (buchitos and coladas) enjoyed by Cubans. In Miami, I have reencountered the rare surnames of some Cuban families I knew in Puerto Rico, such as Sotolongo, Souto, Robaina, Juncosa, Triay, and even Duany. The cultural atmosphere of the club where I spent so much of my youth in San Juan—Casa Cuba—had seemingly multiplied in the vigorous Cuban enclave of South Florida. Little by little, I feel less Cuba-Rican and more Cuban American.

Because of my current position, my teaching and research activities, as well as my public interventions, focus increasingly on Cuba. My location in Miami, my job directing Cuban studies at FIU, and recent changes in U.S.-Cuba relations have placed me in a unique juncture to contribute to reinforcing those bridges to and from Cuba, which inspire the title of this blog.

Since I was very young, I have tried to solve the puzzle of my divided loyalties by keeping in touch with my relatives in Cuba. Returning to Cuba was initially a way to—excuse the cliché—“search for my roots,” to reconnect with a large part of my family that stayed in Havana, and to experience the daily life of a society that has radically transformed since 1959. Since 1981, I have returned more than a dozen times to Havana, where I still have an aunt and many cousins. I once traveled to Santiago, where my father was born and where his ancestors have settled since the late 17th century, the only place where many people know how to spell my strange last name of Irish origin with a y at the end. The founder of the Duany clan in Santiago, Ambrose Duany, arrived in 1678, to help build the city’s San Pedro de la Roca Castle, and married into a local Spanish family.

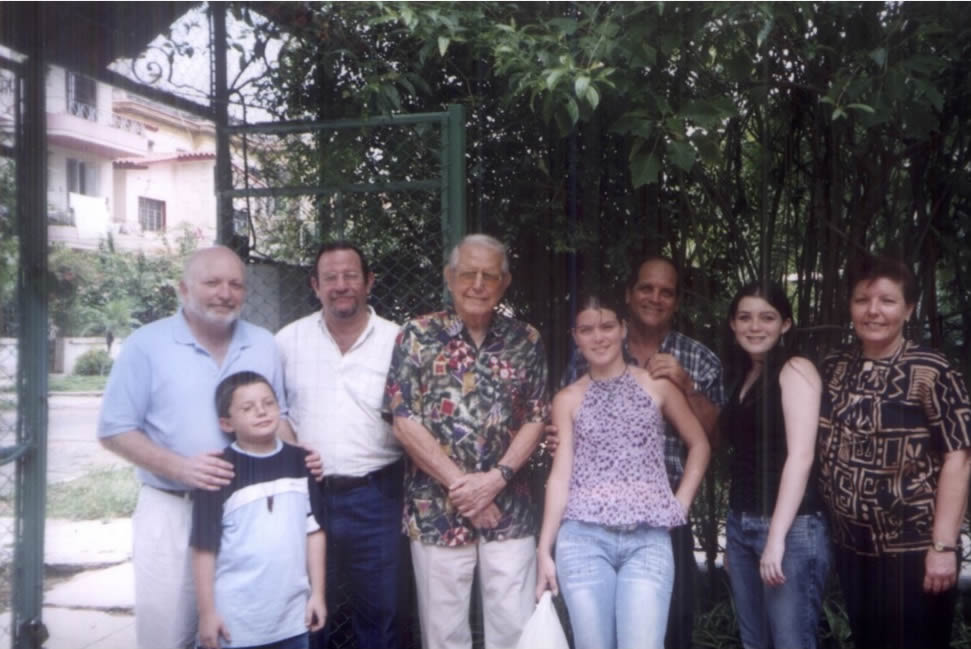

One of my family visits to Havana, with my children, uncle, and cousins, in the early 2000s.

At first, I felt at home, like a prodigal son, thanks to the warm welcome of my extended family in Cuba. I was touched that they still remembered me as “Yoyi,” as they used to nickname me as a child. Reconstructing a past shared by my parents with their siblings, nephews, nieces, and cousins; comparing the letters, photographs, recordings, belongings, and relics they kept of those of us who had left; and knowing (from outside) the house where we lived until 1960 helped me reconcile my family’s memories, split by several decades and many miles. My relatives made sure that I knew where the old Spanish club was located, the multiple houses where my grandmother Mañe lived with her children, the Catholic church where my parents married, and the College of Education at the University of Havana, where my mother and aunts studied and my grandfather Andrés Blanco taught before the Revolution. I felt thrilled to see all these places, as if I could retrace my parents’ footsteps during their childhood and youth.

Over time, I have grown emotionally distant from Cuba, because I know I could not live there: I am inevitably part of a diaspora without a permanent return. Nonetheless, I feel the urgency to visit Cuba whenever I can, even though many of my cousins have left and my uncle Bebo died a few years ago. I felt culturally at ease in Puerto Rico, where I spent most of my life and where I married my Cuban-born wife (who was also raised in Puerto Rico), had two children who now identify as Puerto Rican, and worked for nearly three decades. At some point, I preferred to say, “I live in Puerto Rico, but my parents were Cuban.”

Until recently, I was comfortable with the idea of belonging to the 1.5-generation of Cuban immigrants. The first time I learned about this intermediate classification was probably reading the Cuban-American literary critic and poet Gustavo Pérez-Firmat, who in turn borrowed a category coined by the Cuban-American sociologist Rubén Rumbaut. Following this scheme, I found myself straddling the first generation, born and raised in Cuba (like my parents), and the second generation, born and raised abroad (like my children). However, I later met Rumbaut and he told me emphatically that I was not a part of the 1.5-generation, but rather the 1.75-generation. According to the sociologist, this term refers to people who were born in one country, but moved to another before they were five years old and entered school.

In this regard, my personal experience is closer to the second generation of immigrants than to the first. I do not have a single memory of my early childhood in Cuba; I learned to read and write outside the Island, and I acquired a stronger Puerto Rican than a Cuban accent when speaking Spanish, after losing my Panamanian accent. I am not sure what is the purpose of fractioning an immigrant’s cultural identity in so many decimal points (1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2.5, etcetera), but I am aware that my “Cubanness” differs from that which characterizes those who were brought up on the Island and emigrated as adolescents or adults. I know that the question of cultural identity has fascinated me and perhaps obsessed me, at least since I began my graduate studies.

Three of my siblings and me in Panama during the mid-1960s.

Much of my academic work has centered on the problems of socioeconomic and cultural adaptation of immigrants from the Hispanic Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic) in the United States and Puerto Rico. My own diasporic condition (insofar as I belong to a population displaced from its original territory, but which sustains strong links to it) has led me to inquire into how other people integrate into alien environments and how they nurture their emotional, family, and cultural ties to their places of origin. Like many migrants I have met throughout my research, I too find it indispensable to remain connected with my home country. Having been born in Cuba, raised in Panama and Puerto Rico, studied in the United States, and now living in Miami have marked me indelibly.

One result of these multiple moves has been an incessant linguistic shifting throughout my life. Spanish has always been the dominant language at home for me, but I learned English in elementary school, and I now read and write it every day. Spanish is the primary medium for my most intimate thoughts and feelings, while English is a more academic and professional mode of expression for me. I suppose this linguistic split is part of many migrants’ lives, as well as a sign of increasing cultural hybridity. In my current daily routine in Miami, I continue to speak more Spanish than English, both at home and in the office, and both languages sometimes overlap in that blend pejoratively labeled “Spanglish.”

Being the son of immigrants (I am not sure if my parents considered themselves “refugees”) has inexorably led me to probe the dilemma of identity, especially when the sources of that identity are fragmented. Returning to Cuba, if only infrequently and for short stays, has helped me regain my sense of wholeness and connectedness to my native country, early childhood, and dispersed family. Right now, I have close relatives in eight different countries: the United States, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Panama, Chile, Spain, Switzerland, and Russia. This far-flung family map reflects some of the complicated trajectories of the contemporary Cuban diaspora. However, it has always been challenging to keep in touch with such a scattered kinship network.

I still remember those long-distance telephone calls from my childhood and adolescence in Panama and Puerto Rico. The collect calls from Cuba usually came through late at night or in the early morning. The Cuban operator would identify herself and then all the members of my family would huddle around the telephone. You had to scream because you could not hear well and speak quickly because the call cost a small fortune. My mother would ask each one of my siblings and myself to briefly greet my grandmother Mañe, who had remained in Cuba after the Revolution and whom we would never see again.

In this family portrait, my mother is surrounded by her five children (and the family cat) in Bayamón, Puerto Rico, during the late 1970s.

Communication was precarious, sporadic, and sometimes strained because of the political differences between those who stayed in Cuba and those who left. Letters could take months to arrive and Cubans living abroad could not visit Cuba until the late 1970s. My mother managed to board one of the first flights by Cubans living abroad, a long and expensive journey through Jamaica. At last, she was able to reunite with my grandmother, after nearly 20 years of failed attempts to meet in Canada, Panama, or some other country. Mañe passed away shortly after that trip, which was historic for my family as it was the first time one of us returned to visit Cuba. Soon I would go back as well.

On July 20, 2015, I witnessed, through a television broadcast in Miami, the official opening of the Cuban embassy in Washington, DC. Amidst public manifestations in favor of and against that symbolic act, there was a poignant silence when three Cuban cadets hoisted the Cuban flag and Cuba’s national anthem was played. In my view, the silence meant that most of those present showed respect for the traditional symbols of Cuban nationhood, regardless of their political ideology. It was the first time that such ritual events had occurred on those premises since the United States broke diplomatic ties with Cuba on January 3, 1961, soon after we left the Island.

At the television studio where I sat at that moment, a reporter asked me about the significance of the ceremony. I began to put together an academic response, trying to weigh in between the extreme positions that praised or condemned the restoration of official relations between the two countries. Nevertheless, the reporter insisted on knowing what I felt on that occasion. Then I thought about those telephone calls to Cuba that often woke me up as a child and teenager. I thought about how much my mother had suffered because of her lengthy separation from my grandmother, and I remembered how much we missed not having Mañe close to us when we were growing up. I thought about not knowing my uncle and aunts and my cousins in Cuba for years. Moreover, I thought that any measure that promotes greater contact and communication between Cuban families here and there would be constructive. I believe that the emotional bonds between our family members are stronger than any political differences that might have divided us because of the Cuban Revolution.

I hope that the exorbitant costs of passports, visas, telephone calls, electronic messages, and remittance-sending decrease substantially, so that Cubans from here and there can interact in a more fluid and regular way. I hope that the opening of the Cuban embassy in Washington and the U.S. embassy in Havana will contribute to closer ties between families in Cuba and in the diaspora. I trust that my mother and grandmother, may they rest in peace, would also harbor this hope.

Transplanted to my new home in Miami, 2017.

I felt a great burden upon inheriting my mother’s role as a safekeeper of those fragile family links that must continually be renewed across generations, long distances, and ideological discrepancies. Returning to Havana every so often is a way to not burn the bridges back “home.” Even though I might never return to live there again, I would like to claim, with the exiled poet Heberto Padilla, that I have always lived in Cuba, if only in my mind. Instead, I am now living in Miami, so close and yet so far away from my native city, like so many other compatriots who have chosen to remake their family and professional lives here. I feel very fortunate to have reencountered my Cuban roots in this crossroads of nomads and to dedicate most of my academic efforts to promoting and disseminating knowledge about Cuba and its diaspora. I have somehow become Cuban as a profession.

Jorge Duany is the Director of the Cuban Research Institute and Professor of Anthropology at Florida International University in Miami. He has published extensively on migration, ethnicity, race, nationalism, and transnationalism in Cuba, the Caribbean, and the United States. He is the author, coauthor, editor, or coeditor of 20 books, including Un pueblo disperso: Dimensiones sociales y culturales de la diáspora cubana (2014).

0 Comments