Many Cubans, like Susannah Rodriguez Drissi and her family, didn’t come directly to the US; instead, they were immigrants first in a “third country,” “un tercer país.” In this evocative essay, Rodriguez-Drissi shares her double-immigrant experience, reflecting back on those layover years she lived in Costa Rica before settling in California, her final destination. A time consumed with the past and the future, unable to fully engage with the present. A time caught between illusion and disillusion, between yearning and resignation, between location and dislocation. A time she analogously returns to now as she finds herself—like all of us—suspended emotionally in the midst of this paralyzing pandemic.

Abrazos,

Ruth and Richard

By Susannah Rodríguez Drissi

Read post in Spanish >>

My children dash across the yard and up the deck’s wooden steps. They’ve spent the last hour jumping on the trampoline. Along with muddy footprints and trailing leaves, they drag the remains of the day behind them, as if they’re still getting used to the quiet, and the unexpected freedom, of this new COVID era of our lives.

I listen quietly for sounds of joy. But there are none. Unflinching, my children have exhausted their tolerance for too much time to waste. Somehow, even in this future, where we take careful inventory of our days, my children spurn the seconds, minutes, and hours on wooden decks, and rocking chairs, and dining room tables.

“Back so soon?” I say.

They’re simply unimpressed by time, its delicate texture, its shadings, the broad arc of memories nested at the center. As I watch them run away, disperse into other worlds, the underground emotional and psychological plexus that’s secretly holding everything together gives way. I feel unsettled, heartbroken.

(From left to right) Author’s daughters Kamila Maia Drissi and Leila Nauelle Drissi, San Diego, California.

In Costa Rica, we knew what it was like to float from day to day, to look down long vistas of time. We knew to sit quietly on park benches, and bus stops, and church pews, decoding the heavens for signs of airplanes on their way to California. Perhaps my want to remember Costa Rica, in this time of wildfires and COVID, is simply, at least in part, another demand of the times: the need to recall what waiting felt like, how gradually it filled the spaces where future plans should be. How predictable, like the rain or seasons changing, it became. How much joy and laughter and play there was in waiting, and how dreaded it became.

I wish I could remember the exact day in winter 1981, when time moved in a spacious present, barely outpacing the rhythm at which we got used to it, the rate at which we yielded to its liquid middle. We had been in Costa Rica for exactly a day, but the rain was already upon us. Water yet again. Cubans, the rain seemed to tell us, are a body engulfed by water—extreme, tempestuous, set adrift, an island turning round and round on itself, with no way out but the sea. But this wasn’t Cuba, and neither clouds nor thunder had presaged the rain. It had caught us by surprise as we aimlessly walked down this or that street without a sense of direction, pointing at the bars on every window, at buildings, places, fruits, and people whose names we’d never heard before: “Pulpería, periférico, Alajuela, Guanacaste, jocote, Ticos and Ticas,” we whispered, laughing at the strange Spanish tickling our tongue. My sister and I lagged behind, dipping into bushes at random to watch the water splash. Then I noticed it—a row of blue, green, magenta, pink colors. “Chupa Chups,” the street vendor said, furrowing his wiry brows. He’d taken cover from the rain under an awning, but had left a modest assortment of sweets on display. That instant under the rain—love-struck by what I quickly deduced were Costa Rican pirulís—I became an obsessive stalker of Chupa Chups.

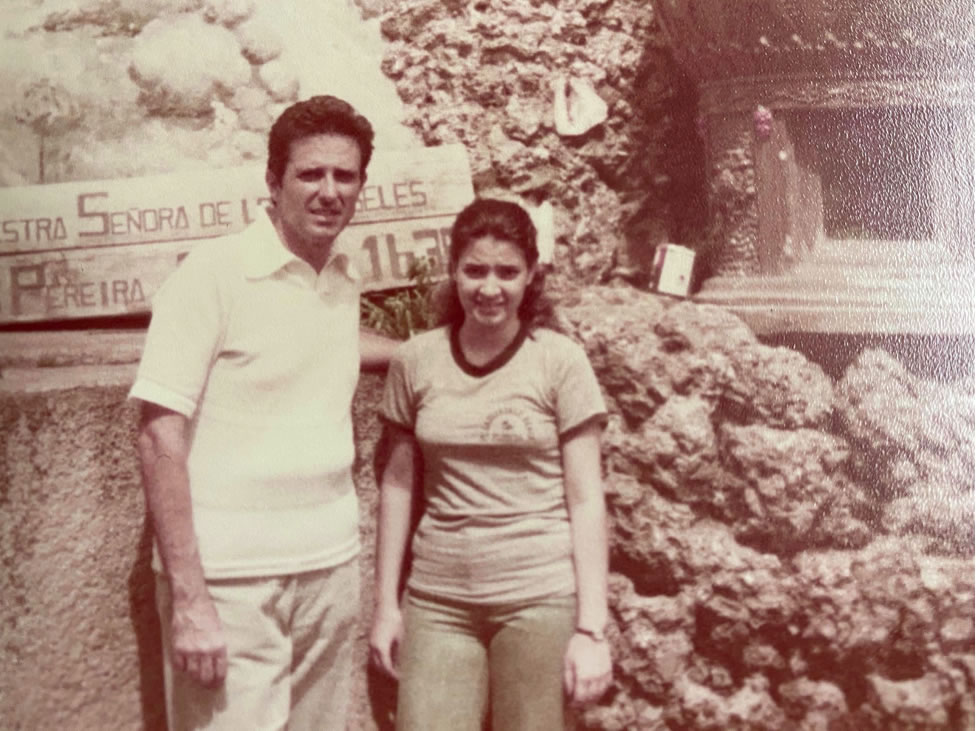

(From left to right) Author with younger sister Susette Rodríguez, San José, Costa Rica, 1981.

When we finally returned to what would become our first home away from home, soaking wet and shivering, my parents rubbed their eyes and cleared their throats—so much of what they’d seen and spoken was foreign matter. Their fondness for this brand-new world would swell and break, and swell and break again. For me, however, desire, once awakened, would taunt me at every turn. So, when I noticed the small bag filled with chocolates at the top of the refrigerator after returning home, amid the purple guarias moradas and delicate orchids of Costa Rican urban life, I yearned for more.

Tense calves, and long, wet tresses dripping water on the gray linoleum floor, I raised my arms toward the ceiling, then pitched forward. My fingertips barely sensed an edge—at nine, I simply wasn’t tall enough to reach.

“You’re soaking wet and messing up the house!” my mother shouted from the bedroom.

But she couldn’t see me, so I pretended not to hear. I dragged a chair and pushed it against the refrigerator door. Then I climbed on top. In that distant afternoon, raindrops pelting like rocks outside a window, I discovered chocolate, ignoring Costa Rica’s flowers, while my dad fumbled with a blow dryer in another room and my mom towel-dried my sister’s hair.

And there was all of that rainfall. Thump, thump, thump it fell on everything. All was made of water, even Jell-O, my dad liked to say. Costa Rican rain does a tricky thing of being at once urgent and painfully slow (every drop is noticed). For us, the thirty-some Cubans newly arrived at the hillside apartments of Montelimar, in the Turrubares of San José, the rain—like the chocolate, and the gelatin, and the Corn Flakes, and like so many things we had only just discovered—was imbued with depth and color and all the possibilities of a blank slate. Everywhere we turned, falling water fanned and sprawled with optimism.

(Adults, from left to right) Julio Arrítola, Aleida Rodríguez, Juana, Jesús Rodríguez, Deisi Arrítola. (Children, from left to right) Javier Arrítola, Susette Rodríguez, Susannah Rodríguez, Jacqueline Arrítola, San José, Costa Rica, 1982.

Time passed slowly, with the sweet cadence of childhood. To set days apart, my family visited other Cubans. We, all of us, the Cubans of Costa Rica, ate popcorn, and strawberry Jell-O, and watched entire films that, though not new, were new to us. We, parents and children alike, discovered Hanna-Barbera’s Charlotte’s Web, and Benji, and Clash of the Titans. And developed an all-consuming obsession for the rising stars of Chiquilladas and Siempre en Domingo. “America,” Raúl Velazco’s theme song insisted, was “la fiesta más grande, la más importante.” Like soundtracks, the films and songs busied our days with the luminous dignity endowed to all that is most human: endurance, and toil, and fear. All the while, time passed.

Some of us adapted better than others. My sister and I walked to the local public school with other Cuban children. She traipsed beside me and kept to herself, her large brown eyes eating up the world as far as she could see. Because I’d always liked to talk to strangers, I met Jenisú, a round face, and sunshine most always, and another Susana, timid and bittersweet, like a question mark, and stayed away from Violeta, whose purple kissy neck marks made us stop and stare. She was, in our young minds, a drastic reversal of the Catholic values we learned in Sunday school.

My dad looked for odd jobs painting or building houses, and the uneasiness he felt was sated only with more unease. And therein lay his greatest strength: he found a temporary cure to his seemingly endless discomfort. Meanwhile, he made plans. Silvered glittered plans that made our infinite waiting possible. In California, we would have a house with a pool, he’d tell us, a car, and a beautiful dog. Too often, his plans became our armor against waiting, and we wondered how we would get through life without them.

(From left to right) Fernando and Hortencia Casteleiro, Cartago, Costa Rica, 1982.

In the end, though, it was my mother who stared out beyond the bars of our apartment window and saw an island. Through the essential medium of her own voice (she sang), she thrust aside our present lives in favor of the lives we’d left behind. She sang lyrics about loss, and loneliness, and regret, bringing into the present moment, that was born from all preceding moments, a kind of despair. At nine years old, I would grow old and soft singing these same songs. This was not home, my mom’s voice sang, not by a long shot.

We, the Cubans of Costa Rica, made peace with waiting. Because waiting enveloped everything with a kind of mid-afternoon languor, we wrapped ourselves with it. Good things come to those who wait, we told ourselves. But underneath the quotidian and seemingly tolerable experience of waiting was a little anxious clock. It came from somewhere deep—from the need to settle down, to plant seeds and grow roots. It came from seeing those Cubans we’d just met leave to their final destination: one to Miami, Orlando, or Tampa, the other to New Jersey, Tucson, Dallas, or New York.

In that great moment of waiting, we reached for their faces and their hands, we sought out their company at odd hours, in doorsteps, and kitchens and living rooms, and the little anxious clock was soothed. And then, when reunion and laughter and dance in the company of others were possible, our tense muscles gave way to a kind of soupy contentment. We waited for life to begin in California and asked very little of our current life. We felt safe, nestled in the warmth of an imaginary Cuban island whose matrix was some 1477.75 miles away from Costa Rica.

A year has passed since we arrived in San José, and I hunt my younger sister down the street with a pair of scissors. I laugh, while she squeals. I won’t hurt her, but I want her to think I will. We play pirate in abandoned lots, and grrr-grrr-grrr! with toothless Cuban children and other neighborhood kids. Jenisú, Susana, and Violeta are only school friends—they’re never part of our games. We run wild, eat Meneitos, and drink ice-cold orange Fantas from pulperías whose only goal in life is to send us packing. Pura vida! We shriek. We memorize antiacid commercials and discover The Flintstones and color TV at a classmate’s home. We couldn’t believe our eyes. We never could believe our eyes. And in the meantime, we waited. We were always waiting.

On our second year, my father announces we are finally leaving to California. My sister and I, echoed by a different crop of toothless Cuban children, prepared for the inevitable by learning English: One-Two-Three-Four-Five and A-B-C-D. Someone found a long-play of Disney songs. Em-I-See-Kay-Ee-Y-Em-O-U-Es-Si. It was our goal to speak English. The thought of going away was a distraction from the void in the pit of the stomach, from the general nervousness about leaving Costa Rica. I would lie on the bed, my heart pounding, holding one arm to the void. Gazing up at the ceiling, I’d count all the friends I’d have left behind by the time we would arrive in California: Jenisú, Susana, Carmita, Jaqueline, Violeta, and all the toothless Cuban children of Costa Rica. But days after my dad had delivered the news of our departure, he delivered the news of a new delay. “Because that’s the way things are,” he said shortly. I was relieved: maybe time would unbend a little now, and we’d get to stay longer, after all. Because the truth was that on most days, standing at the edge of the rain, reaching out my fingers, there was no place I’d rather be. It was only when the rain stopped, when the day turned still and cloudless that I felt the sudden need to lurch forward, to leave. Like the rain, wanting to remain or to leave came in curious waves. At the moment, I was thankful we were staying put.

(From left to right) Ofelia Casteleiro, Hortencia Casteleiro, Concepción Queipo, Susannah Rodríguez, Aleida Rodríguez, Susette Rodríguez, Jesús Rodríguez, San Antonio de Escazú, Costa Rica, 1982.

Those years in Costa Rica meant so many joys, so many dog-eared days we went back to again and again. There would be many delays. So much packing and unpacking because they knew our last name was Rodríguez at the American embassy. And Cubans seemed to get on planes to the U.S. in alphabetical order, a Cuban named Suárez told us. He’d been waiting decades to leave. We were lucky, I thought—we, too, were meant to wait longer.

On year three, time all at once became heavy. I suppose as we stacked days upon days, the little clock grew impatient, and I was sure I could hear him humming in my parents’ ears, as their will to wait gradually grew bare; and everything around us became packed or given away to those whose name was still at the bottom of the list. We were going away—our time had come. For the most part, my family had grown ready to leave, to walk out on the waiting, and the rain, and the Cubans, our beautiful Cubans of Costa Rica, when the time came.

“I’m tired of waiting,” my oldest daughter says. The sun trickling in through the window catches on her dark-brown eyes and she appears, as she often does, troubled by too many questions. “When are we going back to normal life?” She’s come for reassurance that all’s well, after all, and slouches on the couch—her legs scooped to one side, her torso bent in the opposite direction—waiting for me to acknowledge her presence.

“Soon,” I mumble. “Soon.”

Wishing, willing myself to remember, I set out. It is late afternoon and a low sun darkens the deck. A short distance away, my children and my nieces chase each other with plastic Star War lightsabers on the grass. “Chocolate!” I yell from the deck. I’ve decided to test the waters. They choose to ignore me—I don’t blame them. It’s a special occasion, the first time in many months, they’ve gotten to spend time together. They indulge in fresh air, and close contact, and childhood games on the grass, so ubiquitous has been their absence in their lives. Somehow, I can’t help but think that this waiting everyone calls a global pandemic has been a certain kind of gift for my children. It will define them. They’ll treasure the freedom to come and go as they please, and school buildings, and gatherings with family and friends in tight quarters.

Buoyed by a kind of wishful thinking, I squint toward the distance. I rise through delight and wonder, and through all the newness that was our life in Costa Rica, a free and easy place we almost called home for three and a half years. We learn to wait again, I say to myself. Suddenly, unexpectedly, that other world we left behind so many years ago appears at last.

Adultos, de izquierda a derecha: Amarilys, América, Enma, Minor Sibaja, Deisi Arrítola, Julio Arrítola, Yamilet Sibaja, Juan Carlos. Niños, de izquierda a derecha: Susette Rodríguez, Javier Arrítola, Jacqueline Arrítola, Susannah Rodríguez, Nela Sibaja. Aeropuerto Internacional Juan Santamaría, Alajuela, Costa Rica, 1983.

*

This piece is dedicated to Fernando, Ofelia, Concha, and Hortencita – Daisy, Julio, Jaqueline, and Javier –Lalito and Carmelina Crespo – Nancy, Kike, and Kikito – Adita “Maní,” Eduardo, and Yamilet – América “Titi,” Raúl “La Fiera,” Enma, Raulito, and Amarilis – Minor, Marianela, and Yamilet – Anabel Núñez de Giménez – Ida, Antonio, Maria, Damián, Carmita, Mercedita, y Toñito – Maria Ester “La de la pulpería” – Juán Carlos and family – Oscar Muxo de la Cuesta “El Doctor,” Maria Auxiliadora “Ausi,” and Alejandro – Gladys Maduro – Aleida, Jesús, Susannah, Susette Rodríguez, and Ena Rosa Rodríguez “Tía Mimi.

Susannah Rodriguez Drissi is an award-winning Cuban-born writer, poet, playwright, translator, and scholar. Her work has appeared in journals and anthologies such as In Season: Stories of Discovery, Loss, Home, and Places in Between, which won the 2018 Florida Book Award; Publishers Weekly; Los Angeles Review of Books; Miami Herald; Nuevo Herald; and Diario de Cuba, among many others. Her musical, Nocturno, will premiere in Miami in 2021, directed by Victoria Collado (Latin History for Morons), with musical direction by Jesse Sánchez (Hamilton). She is the author of The Latin Poet’s Guide to the Cosmos (Floricanto Press, 2019) and is on the faculty of the Writing Programs at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her novel, Until We’re Fish, published in October 2020 by Propertius Press. Until We’re Fish was nominated for the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, the PEN Open Book Award, and the PEN/Hemingway Book Award.

Ariana Hernández Reguant is a visiting research scholar at Tulane University’s Cuban and Caribbean institute and has written extensively about Cuban and Cuban American culture and society. Her translations have appeared in this blog previously, here and here, as well as on other blogs. She was the founder and editor of the webzine Cuba Counterpoints.

0 Comments