Hola Reader-Friends,

Our blog until now has featured the visions and voices of Cubans of many different backgrounds who hold a variety of perspectives on the island, the diaspora, and their identity. Only occasionally, so far, have we featured the work of writers and artists who aren’t of Cuban descent. But now and then, you find yourself in the presence of an “honorary Cuban,” someone so close to being Cuban they can claim the title, or so devoted to everything Cuban that those of us who are Cuban need to stop and listen to what they can tell us about ourselves. One such honorary Cuban is Anthony DePalma, and we are delighted to include his essay, “The Truth in Bronze,” on our blog this month. DePalma is an extraordinary New York Times journalist who has reported about Cuba for almost four decades, and he is the author of the classic book, The Man Who Invented Fidel and the newly-published gem, The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times. In his essay, he meditates on the meaning of monuments and their absence in Cuba which is equally interesting and not usually discussed. We hope you’ll find his essay as compelling and provocative as we do and look forward to your comments.

Abrazos,

Ruth and Richard

by Anthony DePalma

José Martí is everywhere in Cuba. His busts, white as chalk, spread like dandelion puffs that have taken root in front of every school, near every hospital, close by any corner where Cubans gather. The sculptures, like the man himself, are revered all over the island as well as in the United States, which makes what happened in Havana at the outset of this topsy-turvy year so perplexing.

While Cubans were out celebrating on Jan. 1, eleven of those busts of Martí in and around Havana were splattered with pig blood. Shock and denunciations followed swiftly, and it was no surprise that soon two Cubans, Panter Rodríguez Baro and Yoel Prieto Tamayo, were arrested and accused of having taken money from Miami counterrevolutionaries to vandalize the busts. Cuban television broadcast a long report detailing the actions of the accused vandals and exposing their alleged connection to backers who, officials claimed, worked hand-in-hand with a mysterious group identified as Los Clandestinos that had defaced the busts in order to sow dissent and make Cuba look violent and unsafe.

Universal Marti, Las Terrazas, Artemisa

Cuban-American activists in Miami denied any involvement with the vandalism and roundly condemned the suspects as though they had attacked Martí himself. However, on social media it was clear that Martí, though universally esteemed, embodies different things for different people. In Cuba, the government constantly links him to Fidel, directly connecting his fight for independence in the 19th century to Fidel’s rebellion in the 20th. But the internet lit up with posts from those who saw Martí’s bust as symbolically bleeding from wounds inflicted by a regime that has hijacked his words and manipulated his message to make it seem he supported ideas that were heinous to him.

The year got off to a strange start in Cuba, and then a global pandemic smacked us hard. Just when we thought it was safe to go outside again, cities all over the world erupted in violence against systemic racism in the here and now, as well as in the long distant past. Historic symbols came under attack everywhere. Statues of revered figures in the United States, England and other countries were burned, decapitated, torn down and dumped into rivers. And in the British city of Leicester, thousands signed a petition to remove a monument to the revered Mahatma Gandhi, the pacifist leader of Indian independence, because of the way he mistreated Blacks when he was in South Africa in the early part of his life.

Rage, whether rooted in a desire for justice or simply revenge, often triggers attacks on statues and monuments, frustration ultimately giving way to a pent-up demand for wiping away optics of the past that a new generation finds intolerable. Immediate emotional needs may be met, but injustice isn’t excised, only its symbol. “Waging war on bronze men doesn’t make your life any more moral or just,” Maria Lipman, a Russian journalist who covered the fall of communism, told the New York Times recently. “It does nothing, really.”

Even so, history has been filled with crowds toppling the symbols of their oppressors—from American revolutionaries who tore down statues of George III, to the Russians that Lipman watched knock over monuments to Stalin and other Soviet leaders. Sometimes, it is not an insurrection that calls out the masses but simply an evolution in thinking, as is happening now in the United States where scores of Confederate monuments are under attack. Many were erected in Southern states decades after the defeat of the Confederacy in an attempt to whitewash the war, creating the image of a noble “lost cause” in order to obliterate the memory of what it truly was: a savage campaign to split the country so the horrors of slavery could be preserved in the South.

There may be countless representations of Martí in marble, concrete and bronze all over Cuba, but many people are surprised to learn that there’s not one statue of Fidel. Other revolutionary figures are honored in many cities and towns. A statue of Che Guevara looms over Santa Clara, and Camilo Cienfuegos smiles eternally over the crowds that throng Havana’s Plaza of the Revolution. The regime hasn’t been bashful about commandeering the calendar either, plastering the entire year with dates related to Fidel’s fight against Batista. Even the ill-fated tugboat that was sunk in August 1994 as 68 souls aboard attempted to flee Cuba was named 13 de Marzo, for the failed attack on the presidential palace in 1957.

But except for a bas relief in Camaguey of revolutionary icons, including Fidel, no free-standing statue of him was ever erected during his lifetime because, it is said, he didn’t want to encourage a cult of personality directed at himself, though he endorsed the public adulation of Che, Camilo and others. Glory mattered little to him, he often said, because “all the glory in the world fits in a kernel of corn.” He repeated the phrase so often that most Cubans don’t realize that he had swiped it from Martí. When Fidel died in November 2016, his ashes were placed in a boulder that was hauled to the Santa Ifigenia cemetery in Santiago because, guides there will tell you, the architect who designed the tomb thought the big rock had the shape of a kernel of corn.

Within Santa Ifigenia Cemetery, Santiago de Cuba

Soon after Fidel’s death, the National Assembly passed a law formally prohibiting the commissioning of any statue or the naming of any building, plaza or street to honor Fidel, claiming it was preserving in perpetuity the dying dictator’s wish not to foster any cult around himself. But who needs a statue when his bearded image has been permanently branded on the mind of every Cuban, even those who fled the island, and the simple act of stroking your chin immediately evokes him wherever Cubans are wary of mentioning his name?

Fidel is With Us, Havana

There’s no way of knowing what was in Fidel’s mind when he demanded that statues of himself be banned, but we do know that he lived long enough to watch the huge effigy of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad being pulled down on live TV after the 2003 Gulf War. That happened around the same time that Cuban state security rounded up dozens of dissidents, activists, and journalists in what has come to be known as the Black Spring. It’s not a stretch to think that when Fidel saw Saddam’s statue crash to the ground, he was left with the uncomfortable feeling that if, at some point after his death, Cubans living on the scraps of socialism looked back on the way they had worshiped him in 1959, they might do to his statue what they had done to the memorial to the still living Saddam. Even someone who was as addicted to control as Fidel had to realize that the only way to prevent that kind of repudiation was to banish the statues before they were ever erected.

In their noblest incarnation, monuments have the power to gather individuals around an idea so powerful that it transcends borders. Martí, the fighter with the voice of a poet, who wrote so passionately about liberty and freedom, is celebrated around the world. So robust is the bridge that his words have created that there are replicas of the same statue, a heroic bronze of Martí on horseback, in New York’s Central Park and in front of the former presidential palace in Havana, the latter a recent gift, despite six decades of sovereign enmity between their countries, from Americans to Cubans.

But monuments are not history; they are mythology, a way of remembering a palatable version of the past. Rare is the statue that effectively reveals the complexity of what has gone before. History is simply too labyrinthine to be accurately reduced to a single image, and our need to idealize our heroes is invariably too great to see their obvious flaws. No matter the skill of the sculptor’s hands, it takes not the flowing manes of mighty steeds but the essential energy of written words to convey knotty realities about the way shattering deeds and epochal events shape individual lives.

One of the only such monuments I know of is a plaque in front of a sixteenth century Spanish Colonial church, at Tlatelolco in the center of Mexico City, that commemorates the final battle between Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés (after he left Cuba) and Aztec forces led by the warrior king Cuauhtémoc. In fewer than 40 carefully chosen words, it gives an intricate view of an ugly history: “On August 13, 1521, heroically defended by Cuauhtémoc, Tlatelolco fell into the hands of Hernán Cortés. It was neither a triumph nor a defeat: it was the painful birth of the mestizo nation that is Mexico today.”

Despite its admirable frankness about the origins of 100 million Mexicans, the plaque has its detractors. In 1992, on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival, both Carlos Fuentes and Octavio Paz, two giants of Latin American literature, argued that a multi-layered message like the Tlatelolco plaque may be politically correct, but it is an aberration of reality. Fuentes went so far as to propose erecting a heroic bronze of Cortés on horseback to celebrate his decisive victory in 1521, declaring him the father of modern Mexico, whether Mexicans love him or not. Paz rejected the idea of a statue but agreed with Fuentes that Cortés deserved better. “It is time that Cortes took his rightful place as a historic figure,” Paz said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1992. “He is a figure who has a dark side and a bright side. He is neither an angel nor a devil. He was a great military tactician. He was not a barbarian.”

Decades later, Mexico remains ambivalent about Cortés. The conquistador on a stallion was never cast, and in all of Mexico, there is only one bust of him. It is hard to find, hidden deep in the basement of the Hospital of Jesús in Mexico City, which Cortés founded, and adjacent to the church of Purisima Concepción, where he is buried.

Perhaps both Paz and Fuentes were right in their own ways. Attempting to banish memories does violence to history, but so does vacuous celebration of either the vanquished or the victors. There must be a way of acknowledging the imperfections of those who came before, and the defects of their characters as well as the dark side of their actions, while also crediting their achievements. Bronze men can act as focal points for discussion and debate, though they need not loom over boulevards or stand sentinel before public buildings. They can be placed in museums, parks or reserves that can prompt intellectual explorations by those who want to be there, without intimidating those who are maligned by their messages. Instead of attempting to erase the painful past, the bronzes can stir up understanding of the flaws of those who came before us, while informing us of our own imperfections.

But Cuba is far from achieving that level of sophistication about its recent past. Sometimes I wonder what the old men of the Sierra Maestra—Raúl Castro, Ramiro Valdés, José Machado Ventura, and the other living statues of the revolution–think when their chauffeured Mercedes scurry past the “Granma under glass” behind the presidential palace, now the Museum of the Revolution, in Havana. Do they ever fear a day, in the near or distant future, when crowds with rocks and hammers bust the glass and tip over the old boat the way crowds ripped open the parking meters on those same streets on Jan. 1, 1959? Are they worried that droves of young Cubans are turning their backs on the mythology of the revolution, or that even Cubans who once believed in the promise of the revolution are demanding to know why Santa Ifigenia cemetery has been remodeled so that Fidel’s boulder now adjoins the tombs of Martí and Carlos Manuel de Céspedes as if to link all three to a single revolution, a pretense that defies both history and the truth but serves the purposes of a shaky regime?

“Granma Under Glass,” Havana

Cubans today have grown wiser about their world. As I found out while I spent years researching my new book, The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times, they now realize that the triumphalist world portrayed for six decades in Granma and on state television, in every speech and in every meeting, is merely a fantasy, that the interminable promises they’ve heard of equality and justice, of freedom from want and realization of potential, remain unrealized. “For me, the revolution is lost,” a former high-ranking Communist Party member turned cuentapropista sadly told me. But though she had turned her back on the Party and the revolution, she has remained loyal to Cuba and the notion that la patria, the fatherland, as Martí wrote, is an altar that requires sacrifice, and not a platform to serve oneself.

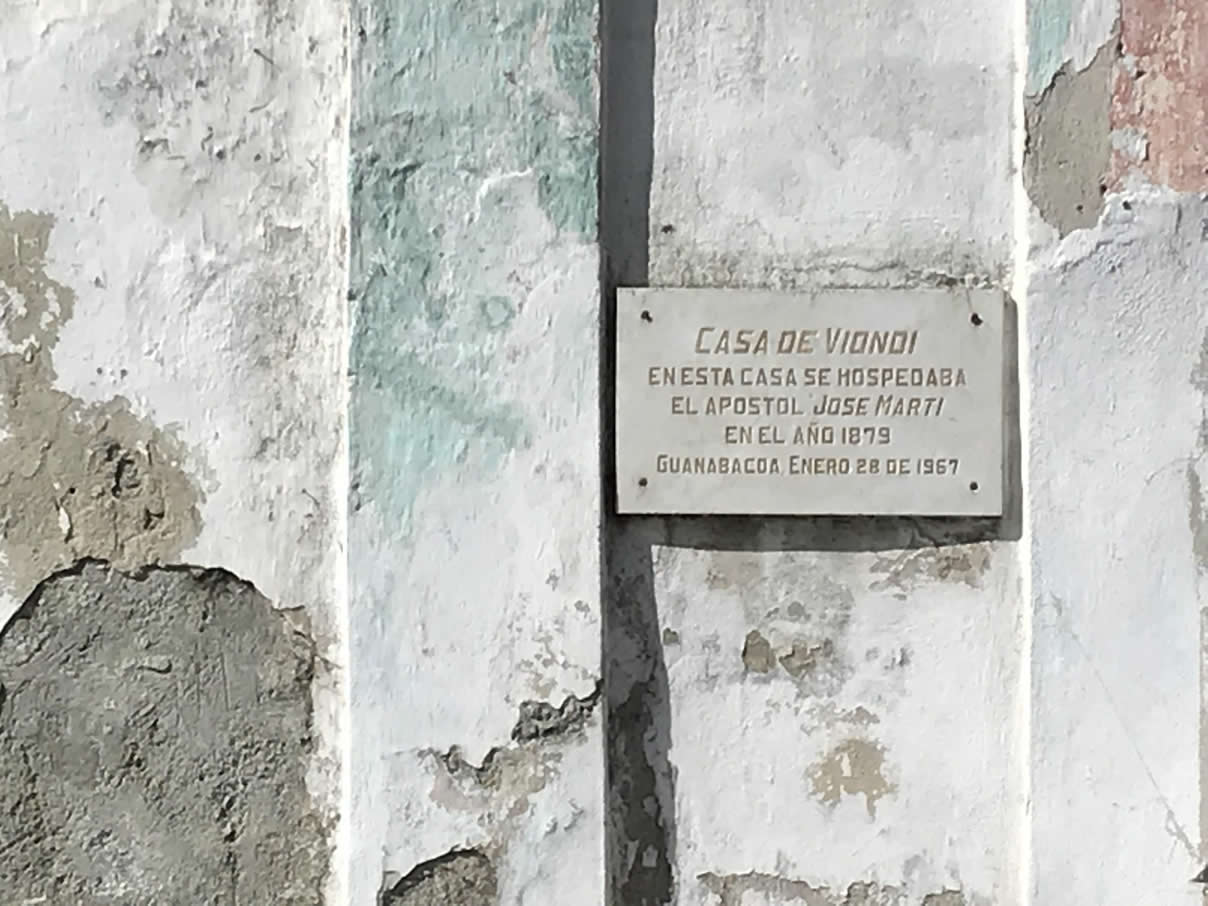

The Apostle Was Here, Guanabacoa, Havana

Cubans are still wary of asking too many questions in public arenas, although they seem to be losing some of their fear. In the 2019 referendum on the “new” constitution, two million who were eligible to vote either did not cast ballots or voted No, an astounding degree of resistance compared to prior elections. And some have ventured to speak out online, openly and without fear, in forums that the government cannot control, asking whose version of history will prevail. It’s still too early for them to lay out what they now know about Fidel and his obsession with power. They must be content with symbols not sledgehammers.

“His fate will not be the tearing down of a bronze figure but the historical judgment against an individual and a system,” Yoani Sánchez wrote of Fidel on her Generation Y blog that is available around the world, though not always in Cuba. “The hardest blow will fall when in a fluid and natural way, in the conversations and memories, the word ‘dictator’ slips in when talking about Castro, while ‘dictatorship’ is used to name his time in power. Those terms, coined by popular usage, installed in memory and ratified by scholars, will be like thousands of hammers beating against the statue of his legacy.”

For those Cubans not satisfied by a hypothetical bashing of Fidel, it might take a Tlatelolco type declaration, set in bronze, to shove aside the bluster and the hate and to arrive at some semblance of the truth. If such a project were to be undertaken at some point in the future when censorship has been lifted and freedom restored to Cuba, what would such a memorial say, and who would compose the message? I’d look for a young poet and an old journalist to collaborate on the wording, one to inject soul and the other to wrap it in perspective. And the result, I think, could look something like this: a plaque bolted to a boulder that resembles a kernel of corn placed on the spot where the yacht Granma was displayed for decades until it was hauled away. Looking back only 50-plus years, not 500 like the Mexicans, presentism—or simply the wisdom of having lived the truth—would be warranted. I can imagine that on the plaque would be words like these:

“On Dec. 2, 1956, heroically blind to what would follow, Cuba was bewitched by the arrival of the yacht Granma and fell into the hands of the inscrutable men aboard who promised a new world but delivered little but disappointment. When these men, their boat and their ideas finally were swept away, it was neither triumph nor defeat, but the painful birth of a wiser nation that is Cuba today.”

Anthony DePalma is a journalist and author of several books, including The Man Who Invented Fidel and, most recently, The Cubans: Ordinary Lives in Extraordinary Times. He was a foreign correspondent for The New York Times for many years, covering Mexico, Canada, and Cuba among other countries. His connection to Cuba is long, his sentiments for the island profound. His wife Miriam was born in Guanabacoa, on the other side of Havana, and came to the United States in 1962. He accompanied her in 1979 when she returned for the first time. When she’d last seen her father, she was just a little girl who looked up at him. When they embraced again, she was a married woman whose fate, and his, had been altered by history. They never saw each other again. Cuba became a personal and professional vocation for Anthony as he covered events on the island, and in other parts of Latin America, for the Times. In 2016, the obituary he wrote for Fidel Castro ran on the newspaper’s front page.

Absolutely true, for Cuba and many more:

“…it was neither triumph nor defeat, but the painful birth of a wiser nation that is Cuba today.”