This month we are thrilled to feature the writing of Ana Menéndez, who made her debut as a writer in 2002 with In Cuba I Was a German Shepherd, a collection of poignant stories of Cuban-American loss and longing. The title story from that book, filled with its sad jokes, honored the exaggerated memories of those who left everything and had to begin new lives again. Now in her piece for our blog, “Can’t Hear You,” written after a return visit to Cuba, Ana reflects on the screams and the silences that characterize the relationships between Cubans on both sides of the ocean border, making us realize that what’s left unsaid is as haunting as what is said. We hope you enjoy her piece as much as we did and look forward to your comments.

by Ana Menéndez

Read post in Spanish >>

Hubo quien se murió del corazón y quien se quedó mudo.

Miguel Barnet, Biografía de un Cimarrón

When I was a child growing up in Tampa, the telephone calls to Cuba were epic shout-fests conducted over dubious connections. Other families, I imagined, punctuated their conversations with declarations of love. In mine, the most common three little words were, “No te oigo!” Can’t hear you!

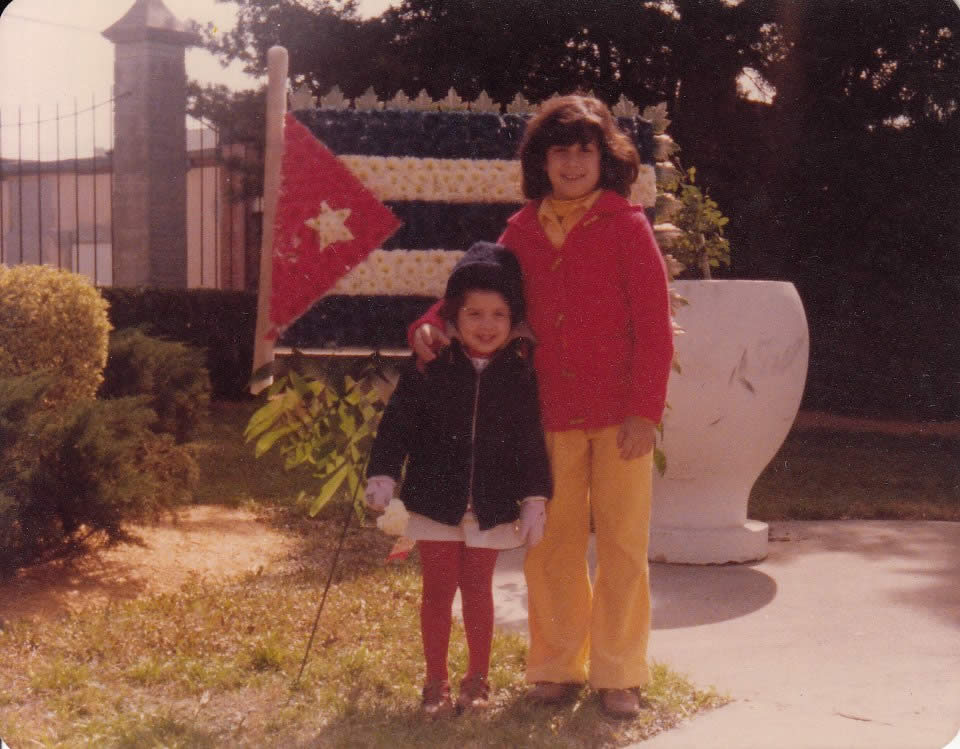

It was the 1970s and though Vietnam and Nixon dominated the news, Cuba dominated our family. To our parents it was a real place, endlessly yearned for. For us children, born in the United States, the memories were borrowed: La Habana was another enigmatic relative, and every conversation with her left you hoarse for days.

Ana putting a white rose on the statue of Jose Martí on his birthday, Ybor City Tampa, late 1970s.

Much has changed in 40 years. But all of us still shout when we talk on the phone, even when we’re in the same city. I recognize it now as a kind of sublimated rage. Listen to me! How did 90 miles become a fortress? How did we get to adulthood without knowing one another? How many more years of shouting before we lose our voices forever?

*

I’ve just landed in Havana⏤my first visit in 15 years. I’m sitting at El Hotel Presidente with a group of my fellow travelers, trying to figure out the wifi, when she suddenly appears, all smiles, on the breezy patio: My cousin Lourdes, whom I didn’t meet until I was almost 30 years old.

Like many Cuban-Americans, I grew up with a phantom family⏤cousins and aunts who stayed behind, carrying on parallel lives in a Havana that drifted farther away every year. Growing up I was always vaguely aware of that other family: my father’s aunt Tula, her daughter Amarilys and her granddaughter⏤my cousin⏤Lourdes, who was just five years older than me.

I knew⏤or was told⏤there had been some unpleasantness related to the Revolution. Support granted or withheld by a relative, a car ride refused at a crucial moment, a cutting remark about patriotic duty. Sometimes, deep into a family gathering when sentiments softened, warm memories would bubble forth, and my father or my aunt would recount stories of shared mischief, a happy childhood by the sea. But usually conversation about our phantom relatives was obscured in an impenetrable and incomprehensible bitterness. Most often, there was simply silence.

For much of my childhood they existed in that other dimension known to loss⏤ghostly voices from a ghostly land that resembled the shadow-planet from a popular television series of my childhood, a place populated by lost things and ruled by an evil dinosaur.

*

My mother left the “Land of the Lost” in 1965 and never returned. My father visited briefly in 1979 and again during the Mariel boatlift. For many years after, there was only the occasional screaming phone call punctuated by long intervals of mute animosity.

The stories of exile have been told so often, and they are so similar family to family, that Cuban-Americans need only shorthand to comprehend: Los milicianos who came to do inventory. The dollars hidden in the shoes. The heirlooms that had to stay behind. The families separated by much more than 90 miles.

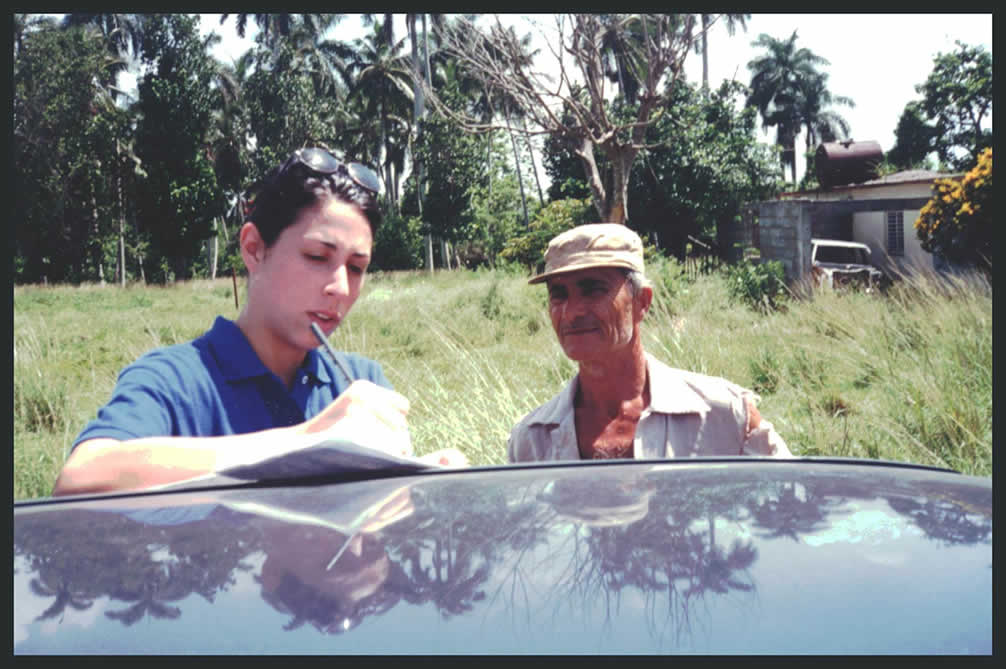

No wonder that along with our parents, my state-side cousins were terrified to visit Cuba. But I was more curious than scared. I became a writer and a reporter because I needed to see things with my own eyes and draw my own conclusions. I wanted to hear the sound of my own voice in this long story. So in 1997, over the objections of both parents, I booked my first trip to Cuba.

I traveled then on assignment for The Orange County Register. I’ve already written about my first, hallucinatory trip, how I cried when the plane landed in my imaginary land. How the landscape leapt out of the old black and white photographs, never to be contained again. And how I realized, with a rending of the self, that although I had been calling myself Cuban all these years, I was, in fact, formed on America’s Sesame Street. The hustle, the history, the struggle of Cuba belonged to someone else.

Ana reporting near her father’s old farm in Cardenas, 1997.

But the image that remains strongest from that trip is seeing my phantom family for the first time. I arrived at their Vedado home with a bag of soap and shampoo, and Amarilys was the first to greet me. We’d never met, but we hugged like long-parted family. Tula⏤that fiercely opinionated warrior I had heard so much about⏤was resting.

I took a seat to wait for her. The living room was darkened by celosias that had been closed against the summer sun, but I could still make out the empty rocking chair, the photo of Che Guevara hanging on the wall.

I had met my great-aunt Tula only once. She had visited almost 20 years before, when I was just a child. I remembered her only as a big woman with a loud voice. I could not be sure what kind of greeting awaited me.

The first thing I heard was the tap tap of a walker. Seconds later she emerged: frail, bent, worn by the many years that had separated us. The lobes of her ears swayed as she walked, just as my grandfather’s had. Thick glasses amplified the watery eyes that now looked up at me. She was 90 years old.

Writing about this moment twenty years ago in The Register, I recalled: “I was suddenly very sad, sad for my family and politics and every intractable posture I’d ever assumed.”

I returned to Havana again in 2002 and this time I cried on departure, which now felt like abandonment. My phantom family had welcomed me with the gentleness and wisdom only kin can provide. I had never felt more at home or more alienated from it at the same time. On that trip, I experienced the distance more acutely than ever. How much had we lost? Where was the childhood we might have shared? I grieved for the vanished emotional and intellectual bonds. And I grieved for my family⏤all of them. But especially for the ones in Havana. They had a vibrant life in the country of their birth, but still, to me, they seemed like the exiles: castaways from the political storm that had carried all of their loved ones away and left them stranded and alone in a crumbling city.

1997, in the Vedado home of Tula (seated). Left to right: Ana, Dexter Filkins, Amarilys, Laura (Lourdes’ daughter) and Amarilys’ husband Guillermo.

Fifteen years passed before I returned to Cuba for a third time. In the intervening years, Tula had died. And the roof of her elegant Vedado house had caved in. I found my family living in a new home in the outskirts of the city, with the same high ceilings and rocking chairs. The portrait of Che had been replaced by contemporary Cuban art. And the walker now belonged to Amarilys. Before I could speak, she shot off a barrage of one-liners that seemed designed to discourage any pity I might be tempted to display.

She confessed that she missed the family, but then, in mock disgust, said that last time she was in Miami, they couldn’t stop crying and blubbering over her.

“Quita, chico, vete pa’llá!” she says she told an uncle.

It was a different story in 2002. Then, Amarilys had just returned from a disastrous first trip to Miami. I heard one version of what happened from my relatives in Miami and a different version from Amarilys in Havana. Somehow, as the single rickety bridge between the family factions, I had become judge and jury to their grievances.

As the Miami relatives had it, Amarilys had been sullen and unappreciative throughout her visit. For every marvel my aunt⏤condescendingly⏤showed her (“Look! Supermarket scanners!”), Amarilys had countered with, “Yeah, we have those, too.” She had spent the whole trip in a bad mood, the relatives said.

From Amarilys’ perspective, the cousins had harassed and hounded her from the moment she arrived.

“Admit that Cuba is a piece of shit!” her relatives demanded again and again, until Amarilys, fed up, shouted, “Fine, Cuba is a piece of shit and I’m returning tomorrow!” And she cut her trip short.

A new round of silence had begun. But to an outsider⏤which I was by now⏤the drama wasn’t so difficult to understand: Both sides had been forced to make momentous decisions at a very young age⏤my own father was just 19 years old when he moved, alone, to the United States. His twin sister soon followed. Meanwhile, Amarilys, barely into her 20s then, had made the equally momentous decision to ride out the Revolution.

At an age when most young people were settling into college, the cousins had to decide whether to stay in their own home with their own culture and language, or brave it in a new land. Forty years later, called to reckon with their decisions, none of them would cede ground. In Cuban lingo, the other side is always completamente equivocado⏤completely and absolutely wrong. Any nuance or hint of regret would be a devastating admission.

Today, most of the bitterness seems to have been sweetened with a brusque kind of love, and, in Amarilys’s case at least, a dogged attempt to avoid sentimentality. The cousins are now in their late 70s and 80s. They’ve buried their parents. They have problems with their health. At some point they must have awakened to the cost of their youthful decisions: an entire lifetime⏤with all its joys and disappointments⏤experienced within the perpetual prison of waiting. It’s a fate that for all their differences, they all ended up sharing.

We in the first generation born after this rupture are now in our forties and fifties. For Lourdes and me, there are no shared childhood memories and little of the intimacy that is built over a lifetime. There is only her sweet attentiveness, gathering me now on a gorgeous Havana afternoon to take me to see the family again.

On the patio at El Presidente she tells me I don’t age, that I’m as beautiful as ever, and I return the compliment⏤both of us suspended between genuine family banter and the awkward pleasantries of two middle-aged friends meeting for the first time after many years.

Ana and cousin Lourdes at the rooftop bar of La Guarida Restaurant February 2017.

*

This time I’ve traveled to Havana in the company of six other writers, led by Ruth Behar. Near the end of our visit, we meet with a literary critic at Casa de las Americas. She tells us a story about a foreigner who marvels at how fashionable the city seems now:

“Un extranjero le dice a un Cubano, ‘Hoy en día la Habana está de moda.’ Al cual el Cubano le responde, ‘La Habana siempre está de moda.”

Havana is always en vogue, the Cuban responds. But after three days in a Havana I barely recognize⏤a city on the move again, with homes for sale and a new unspoken pact with capitalism⏤en vogue is not what I hear.

What I hear is:

“Hoy en día la Habana está de muda.” Y la respuesta del Cubano: “La Habana siempre esta muda.”

*

My fanciful mishearing⏤likely brought about by exhaustion and a worsening cold⏤rested on a homonym. “Muda” (move) in Spanish is the same word as for “mute.”

Most visitors don’t think of Havana as mute. So much exuberance and shouting at all hours. In the popular imagination, Cuba is the land of the loud. But Caribbean history, as Junot Diaz has noted, is “one vast silence.” And I hear Havana’s silence now. It thrums beneath the cacophony that tries desperately to drown it out. It is a silence that stretches back to the slaughtered Taínos, the thousand untold horrors of slavery, the victims of a century of despotism, the murders and suicides of revolution, the uncounted drowned in the Straits of Florida.

It was a friend of my uncle’s from medical school who denounced him in Cuba in the heady days following the revolution. He was sentenced to four years in prison for not knowing how to remain silent.

It was a mob that gagged María Elena Cruz Varela with her own words. Flying goes the voice. Fragile marionette/with invisible strings, she writes in “Prayer Against Fear.”

Within the revolution, four-hour speeches. Against the revolution, the silence of the void.

In Miami you can sometimes catch Havana’s reflection as if in a fun house mirror. There, too, the orthodoxy worked to silence its critics. Luciano Nieves, murdered in 1975 for advocating dialogue with Cuba. Emilio Milian, maimed by a car bomb for publicly condemning exile violence. This is not to draw false equivalences or facile comparisons (which are odious). It is only a realization that what we lived was part of a single, continuously running family drama.

*

I return from Havana on Valentine’s Day. The flight to Miami takes just 39 minutes⏤less time than it takes me to drive from my house on the beach to my parents’ in suburbia. Were we really always this near to one another? What happened to the unfathomable distance that we once had to shout across? No te oigo!

A Nochebuena in Tampa mid 1970s. Ana’s maternal and paternal grandparents and aunts and uncles and two friends.

As soon as I land, I call my parents. I relay greetings from the Havana family, which they accept without comment. It’s only after I tell them about the changes I’ve seen⏤the new real estate market, the private restaurants, the congested roads⏤that my father starts talking and cannot stop: “Así que se venden casas en la Habana ahora? So one can move from one apartment to another? So Cubans can travel and eat in private restaurants? You don’t say! And what of those executed in the firing squads? What of a people’s suffering for more than 50 years?”

And my only response is, “I am in complete agreement with you. You are absolutely correct and I understand you totally. The only thing I can tell you is that Cuba is moving forward. With you or without you.”

The following morning, I wake with a sore throat so severe that I cannot swallow. I crawl into bed and an entire day goes by before I say another word to anyone.

Ana and sister Rosa at Jose Martí Park, Ybor City Tampa, late 1970s

Ana Menéndez is the author of four books of fiction: Adios, Happy Homeland!, The Last War, Loving Che and In Cuba I Was a German Shepherd, whose title story won a Pushcart Prize. She has worked as a journalist in the United States and abroad, most recently as a prize-winning columnist for The Miami Herald. As a reporter, she wrote about Cuba, Haiti, Kashmir, Afghanistan and India, where she was based for three years. Her work has appeared in a variety of publications including Vogue, Bomb Magazine, The New York Times and Tin House, and has been included in several anthologies, including The Norton Anthology of Latino Literature. She has a B.A. in English from Florida International University and an M.F.A. from New York University. A former Fulbright Scholar in Egypt, she now lives in Surfside, Florida.

0 Comments